Folk singer Pete Seeger once posed the question, “Which side are you on boys, which side are you on?” When it came to Jim Ellis, the political right thought he was a card-carrying Communist. The left thought he was a flunky for developers and downtown business. After all, Ellis was the guy who drove the cleanup of polluted Lake Washington, ensured the Washington State Convention Center was located smack-dab in downtown Seattle and earned the moniker “Father of Metro.”

The truth is Ellis, ’48, ’49, a bond lawyer who never held public office, fought for the public good. That was his side. In these highly partisan times, the life of Jim Ellis shows another way forward. Though Ellis died Oct. 22 in Seattle at the age of 98, his achievements continue to benefit everyone who lives in the Puget Sound region—and his legacy will live on.

His civic-mindedness included the UW, where Ellis received two degrees from law school in 1948 and 1949. He served on the Board of Regents from 1965 to 1977, wild years full of anti-war student activism. Emile Pitre, ’69, a founder of the UW’s Black Student Union who went on to serve in several positions in the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity before retiring in 2015, is writing a book about OMA&D. He says Ellis’ role on the Board of Regents was absolutely pivotal in creating policies to provide educational opportunities to women and underrepresented minorities.

“Fifty-one years later, we still have OMA&D, and the Instructional Center, which provides tutoring to 2,000 students each year, and the Ethnic Cultural Center. Jim Ellis was part of all that,” Pitre says.

When angry students in 1968 demanded to meet with some regents, Ellis and fellow regent Robert Flennaugh, ’64, a Seattle dentist, went to a room in the HUB where the meeting was to be held. Two chairs for them had been perched on a table overlooking the entire room.

Ellis in 1999.

“It was like we were going to be kings presiding over everyone,” Ellis recalled in a 1999 interview with Jon Marmor, editor of UW Magazine. He immediately got rid of the chairs and sat on the floor with the students and listened. He did a lot of listening to students in those years. In 1999, for his lifetime of public service, the UW bestowed upon Ellis the highest honor for an alumnus, the Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus award.

Two events in his early life helped form Ellis’ character. Born in Oakland, California, in 1921, Ellis was 2 years old when his family moved to Washington. He was the eldest of three boys. The first event occurred when Ellis was 15. His father dropped him and his younger brother Bob off on 5 acres of woodland his dad had purchased along the Raging River near Preston. The boys had two dogs for company along with groceries. Their mission? Spend the summer building a log cabin for the family. They had no blueprints and no construction experience. In the first four days, a steady downpour soaked them and all their gear. But by the end of the summer, they had built the cabin, although they continued to work on it for three years after that. This experience cemented his close relationship with his brother.

The second event could have turned Ellis bitter and angry. Instead, on the advice of his beloved wife Mary Lou, he channeled loss into something positive—not only for himself but for the community. Ellis and his brother enlisted in the army on the same day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Four years later, Bob was killed by an artillery shell in the Battle of the Bulge in 1945. Jim, who was stationed in Idaho, was devastated by the news and wanted to head to the front to avenge Bob’s death. However, Mary Lou, his wife of three months, offered her young husband wise counsel: Instead of revenge, why not do something to honor Bob? She said, “We could take part of our life and give something to others, for Bob.”

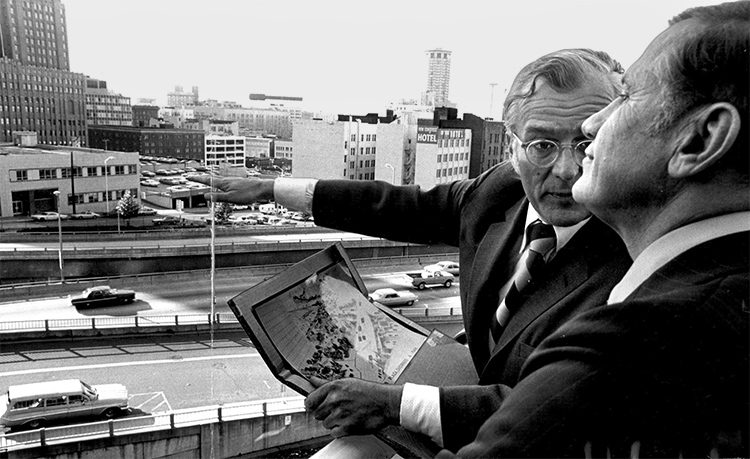

At the future site of Freeway Park in downtown Seattle, Jim Ellis lobbies U.S. Transportation Secretary John Volpe for a lid over Interstate 5. Photo courtesy of The Seattle Times.

Because Bob loved nature, many of Ellis’ causes involved conservation. President Nixon even asked Ellis to serve as the nation’s first director of the Environmental Protection Agency, but Ellis turned him down because he thought he could do more good in Washington state.

Like many veterans returning from World War II, Ellis came home and pursued higher education, enrolling in the UW Law School. After graduation, he went to work for a top Seattle law firm. But he made time for public service, even as his family grew to include four children.

One of his first efforts was cleaning up Lake Washington, which was nearly ruined because millions of gallons of raw and partially treated sewage was dumped into it every year. It took more than five years and one defeat at the polls before voters approved the creation of Metro, a regional government agency that cleaned up the lake. Next was Forward Thrust, an initiative that resulted in the creation of the Kingdome, the Seattle Aquarium, more than two dozen county swimming pools and a bevy of parks, including Gas Works and Discovery parks, and the beginning of the Burke-Gilman Trail. Then he pushed to build a “lid” over Interstate 5 in downtown Seattle to serve as the home for the Convention Center and Freeway Park (pictured at top). He didn’t stop there. In the early 1990s, he chaired the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust, which is dedicated to preserving a greenway along the I-90 corridor from Seattle to the foothills of Kittitas County.

None of these projects was easy, and they generated some vehement disagreements. But Ellis tried not to take anything too personally. He also didn’t care who got credit. He arranged meetings, brewed coffee and photocopied agendas himself. He became famous around town for his battered brown briefcase, from which he pulled every possible document or plan that often made him the best prepared person in the room.

In an interview with Historylink.org, he said, “Life is interesting. If you just refuse to be cynical, it’s really quite fascinating. And in some degree, it’s inspiring to see all our differences and to see that the system—hopefully, hopefully—can still function.” We may not see the likes of Jim Ellis again. But we see his life as a living witness of what one person committed to the public good can accomplish. We’re the better for it.