The race is on to deliver vaccine equity The race is on to deliver vaccine equity The race is on to deliver vaccine equity

story by | Hannelore Sudermann | illustration by Joe Anderson | photos by David Ryder | Viewpoint Magazine | May 10, 2021

In December, when a crate containing the first 300 doses of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine came off a delivery truck at the Lummi Tribal Health Center, the tribe was prepared. Six months earlier, 64 members had volunteered for a UW-administered vaccine trial. It was a goal for the researchers that communities of color who are hardest hit by coronavirus (Latinx, Black and Native American) were included in the trial to ensure the vaccine would be as effective for them as for white test subjects.

In deciding whether to take part in the trial, the Lummi community explored issues of distrust and fear around the vaccine. “There were hundreds of meetings and calls with community members about vaccines in general,” says Doctor Dakotah Lane, ’03. “It was a big ask to get this trial going.” But because of that process, the community and the tribal leaders had had their big discussions about vaccines months earlier. And their participation in the trial meant they had a -80 C freezer already installed at the clinic. When the approved vaccine became available in late 2020, the Lummi had just one of two such freezers in the county.

Lane, a member of the Lummi Nation, grew up around the reservation. Many of his patients are family or lifelong neighbors. He started on his path to medicine started after graduating in engineering at the UW and then serving in the Peace Corps in Malawi. He enrolled in medical school at Weill Cornell Medicine and prepared himself to return to provide medical care to his home community. The first COVID-19 case came in February 2020. “I’ve been a physician here since 2016 and became medical director about two years ago,” he says. “I never thought I would be facing one of the largest generational challenges you could imagine.”

“There are some community pockets ready to get the vaccine, and they’re just waiting.”

Paula Houston, chief equity officer for UW Medicine

Lane is a linchpin between the community and the American medical system. In the past year, he has helped address members’ concerns about vaccine safety and historic distrust of American medicine. Working with elders and tribal leaders, he encouraged other Lummi members and their families to get their vaccines as soon as they were available. The tribe led the country in efficient and equitable vaccine distribution.

The Lummi story is one of success, but nationwide we’re falling short on distributing vaccines to the communities who need it most—that includes Native Americans, who have been killed by the coronavirus at a faster rate than any other group in the U.S., according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. A recent report from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that in the first 2 ½ months of the U.S. vaccination program, there were significant racial, ethnic and economic disparities in vaccine coverage in nearly every state. It’s not just a matter of getting the vaccines to the states, it’s a need for planned and tailored approaches to ensure the vaccines are equitably distributed, says Paula Houston, the chief equity officer for UW Medicine and associate vice president for medical affairs for the UW.

Here in Washington, lack of access, distrust of the American medical system and the need for an organized plan to reach the most vulnerable people are the biggest challenges, says Houston, who has been central to the UW’s effort to distribute the vaccine.

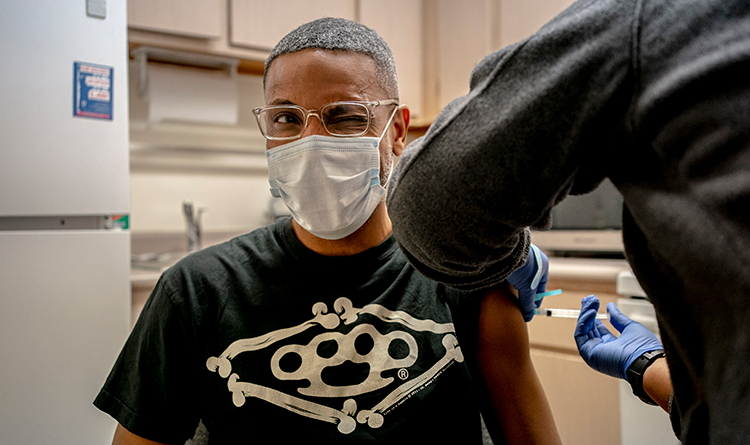

Dion Thoms, assistant manager at the Martin Luther King Jr. apartment complex, receives a vaccine during a mobile COVID-19 vaccine clinic. A UW Medicine team provided vaccines to employees and residents at the Beacon Hill site.

When the vaccines first became available in December, Houston and her colleagues focused on equitably distributing the vaccine to the workers in the UW Medicine system, particularly to people of color. “We started with working on how do we get appropriate messaging to our workforce, particularly to our workforce who is of limited English proficiency, often essential workers who have great responsibility for keeping us running,” she says. Right away, the team realized that communicating only in English and primarily by email wasn’t working. Almost 40 % of the workers they wanted to reach were declining the vaccine. “We needed to do something different as we were rolling out invitations to come get your vaccine,” she says.

The Medicine team launched a series of community conversations (now available on YouTube) in multiple languages. In two—Spanish and English—Santiago Neme, a UW doctor who completed his UW Master’s of Public Health in 2014, explained how the MRNA-type vaccines work. The vaccine tells the body to produce a protein that then triggers an immune response. “It’s not COVID. It cannot cause COVID to folks. We’re mimicking COVID without having any COVID in the vaccine.” What is so extraordinary is that the first two vaccines, Pfizer and Moderna, have an efficacy rate of about 95%, he points out.

Those first two vaccines have been studied in over 70,000 patients and by late winter had been distributed to more than 200 million people worldwide. “They are extremely safe,” he says. He shares his own vaccine experience, explaining that the only side effect for most people is pain around the site of vaccination.

UW Medicine produced at least nine such conversations in languages including Cantonese, Mandarin, and Oromo and Amharic, the languages widely spoken in Ethiopia. “These have been really well received,” says Houston. “We invited employees and their family and community members to join in the viewing. Now as we’re moving into more community vaccines, we’re thinking about how do we do more public vaccine information sessions.”

There’s no mystery as to who they need to reach first. “We know in our Pacific Islander population, there is very high disproportionality in terms of burden of disease. Then it would be the Latinx community and then our Black community,” says Houston. “That’s something we’re particularly interested in right now. We know our Black elders are not taking the vaccine in levels that we would like.” Houston and her colleagues are working with senior centers, churches and community-based providers to remedy that.

Vaccine hesitancy is definitely at play with all of these communities: The distrust of the American medical system is well founded among people of color, says Houston. Black people in this country have had a horrible history in our medical system, having been experimented on since the time of slavery, she says. Some of the beliefs “like Black people having thicker skin and not feeling pain as much, and having blood that coagulates better, these are things that came directly out of slave medicine and from slave owners. … In many ways, the medical community still perpetuates these falsehoods.”

“Native populations have experienced the same kind of atrocities, and even more recently,” she says. And people of color have had their own present-day experiences, feeling like they’re not treated fairly by their medical providers.

All the more reason to go to greater lengths to make the vaccines accessible and to connect with the most vulnerable in our communities. We need these outreach efforts, and we need to be focused on reaching our most vulnerable populations with the vaccines, Houston says. If we aren’t focused, people will slip through the cracks. “What it takes is making different decisions, and we’re making different decisions.”

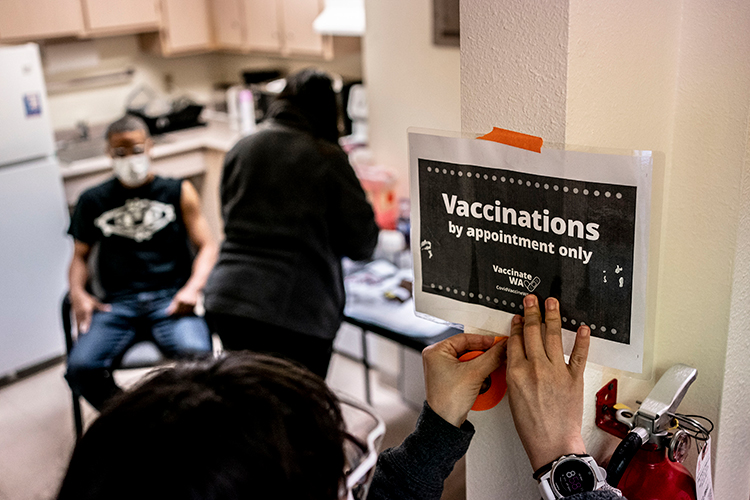

Staff from the UW Medicine mobile clinic began delivering vaccines in mid-spring with an aim to reach medically underserved communities.

One effort is to reach out to communities of color with the help of people of color. UW Medicine celebrated the 100,000th vaccine dose distributed via Wanda Herndon, a Seattle influencer and former Starbucks vice president for communications and public affairs. She celebrated getting her shot on a video, saying, “I was so nervous that I wasn’t even going to get it.”

Like Herndon, not everyone is hesitant. “There are some community pockets ready to get the vaccine, and they’re just waiting,” says Houston. Now the UW is working to find those pockets and determine whether pop-up clinics, a mobile unit or a mass-vaccination site would serve them best.

After a “boot-camp” training, hundreds of students from the schools of pharmacy, nursing, medicine, social work and dentistry have gone to clinics and pharmacies around Puget Sound to help with vaccine delivery. Diep Ngo is one of nearly 90 pharmacy students traveling to clinics to deliver vaccines. Personally, she told UW News, she wants to do more public health outreach with medically underserved people, including her own Vietnamese immigrant community.

Even though it was impossible to know when it would come, “we spent 25 years preparing for the COVID pandemic,” says Don Downing, ’75, the clinical professor in the School of Pharmacy who helped develop the first pharmacist-delivered vaccination program in the country. Through an effort to provide students with service-learning experience through community outreach, the health sciences students and faculty have been building pathways into historically underserved communities. Those relationships with community centers, churches and health organizations like the Somali Health Board are opening doors to distributing the vaccines.

This spring, nearly 1,000 students signed up to be volunteer vaccinators and have been working in clinics throughout the Puget Sound region. “We are ready for this,” says Downing.

Following established connections and forging new ones for the sake of getting vaccines into arms, “we’re learning as we are out doing our community engagement,” says Houston. “We’re also asking how are we going to have a post-COVID presence in some of these communities,” says Houston. The providers want to maintain the relationships they have developed through testing and vaccine delivery in order to better serve all the health care needs of the communities, she adds. “We all just want to do the right thing.”

At top: Jennifer Hernandez prepares doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine during a UW Medicine mobile vaccine clinic at Martin Luther King Jr. Apartments, an affordable housing complex in South Seattle.