At first glance, the room looks ordinary. A random scattering of tables and desks surrounded by snaking computer cables. A giant whiteboard covered with scribbles.

Here and there, bespectacled grad students huddle in front of laptops or looming 30-inch monitors, munching chips or Cheerios out of plastic sandwich bags.

But the everyday look of these students and scribbles and pulsating computer screens belies the true nature of this room. Because this is the University of Washington’s Center for Game Science, where a handful of creative thinkers are devising a series of games designed to help solve puzzles that—for years—have tormented everyone from scientists to sixth graders.

“Basically, we’re focusing not just on scientific discovery games but, in general, games as a primary medium for solving really hard problems that our entire society cares about,” says Zoran Popović, associate professor at the UW’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering and director of the Center for Game Science.

“Specifically problems that people alone or computers alone cannot solve. But together they might be able to.”

Fun with proteins

One such problem is that of protein folding, one of the toughest nuts to crack in the world of molecular biology.

“Everything that needs to be done on a cellular level, an organism level, is done with protein,” says Popović. “From digestion to defending against diseases to anything else you can think of, proteins are doing it. And anybody who understands how to make proteins that do exactly the right thing knows the secret of life.”

Cracking the code to a protein’s fold could lead to new ways of combating disease, creating vaccines or designing new biofuels, says Popović. So far, though, using large-scale distributed computing to predict the three-dimensional structure of various proteins—or determine how proteins fold—has only had limited success.

And that’s where the game Foldit comes in.

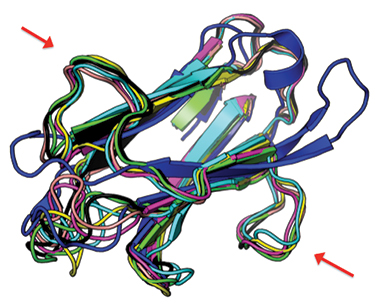

An image from the game Foldit, which UW researchers are using to figure out protein folding.

Developed two and a half years ago by CSE grad students Seth Cooper and Adrien Treuille, ’04, ’08 (and inspired and advised by Popović and UW biochemistry professor David Baker), Foldit uses the brainpower and 3-D spatial reasoning skills of thousands of computer game players to puzzle out the intricacies of these strange squiggly proteins.

Using models of various proteins such as “HIV protease” and “unsolved monkey virus protein,” Foldit lets players grab, pull, bend and manipulate each protein’s individual components using a host of tools. Each of the more than 600 proteins in the game has its own unique shape, some resembling jungle gyms on steroids; others, lower intestinal tracts bristling with arms (or “sidechains”) shaped like tennis rackets or lightning bolts.

After a player moves the pieces this way and that, the game evaluates the fold (using research done by the UW Baker Lab), then awards the player a score. Scores are then posted on a leader board, which allows for competition between individual players (and teams).

“Computers look at every possibility with equal importance,” says Scott Zaccanelli, a 48-year-old production planner from McKinney, Texas, who plays under the name Boots McGraw. Without reasoning skills, a computer will try each minute iteration of a fold pattern one at a time. “People can look at it and say ‘That doesn’t look right. It looks like this part should be over here and in this shape.’ We can spare the computers millions and billions of computing cycles by not bothering to go into the directions that don’t look right.”

So far, Foldit has attracted more than 100,000 players from around the world, most of whom have no background in biochemistry, and, according to an August 2010 paper published in the journal Nature, has shown that in certain instances—particularly those where intuitive leaps or major shifts in strategy are called for—the game and its group mind actually outperforms the supercomputers.

“Foldit was the first test trial of an idea like this,” says Popović. “Through game play, it allows people to become experts to the point that they’re able to really truly advance science. And now everybody’s jumping on the bandwagon. Every other day, some other scientist is calling me about a particular scientific problem and how to turn it into a game.”

Cameras, castles and cute aliens

And there are other games in play at the Center.

PhotoCity uses crowd-sourced photographs and computer vision technology developed at the UW to create stunning 3-D images of buildings, neighborhoods and cities.

“The game is designed to get people to go out into the real world and take as many photos of a building as possible,” says Cooper, who is now also the creative director of the Center for Game Science. “We then use those photos to make a 3-D computer model of the building.”

Developed by CSE grad student Kathleen Tuite, and leapfrogging off of a Photo Tourism project designed by CSE alum Noah Snavely, ’05, ’08, PhotoCity is currently collecting photos of buildings in Washington, D.C., Tokyo, Barcelona and points beyond. Here at home, the developers have created “seed models” of the Fremont Troll, the Lenin Statue and the Ballard Canal, as well as an ever-expanding 3-D version of the UW campus that, as of this writing, has gleaned more than 50,000 photos.

As with other video games, PhotoCity doles out points and virtual conquests to those who perform the best; in this case, the players who take the most photos are awarded flags and castles.

And the strategy works.

“At first, I thought it sounded goofy but then I ended up really getting into it,” says Emma Lynch, a 22-year-old UW computer science major who says she’s now “addicted” to PhotoCity. “I went out and took pictures of this one building and then uploaded them and was like ‘Wow, I can see where my pictures made a real difference.’ Plus, I could see where I was beating or losing to my friends. The competition starts to drive you.”

Cooper says the game is much more than just a game, though.

“Creating 3-D models is expensive and time-consuming,” he says. “Our end goal is reconstructing a 3-D model of as much of the world as possible—all through people playing this game. Over time, you’d have a record of how a city changes and how the world changes.”

Changing the world of education is what drives yet another game developed by the Center. Refraction, a prototype math game developed by Popovic´ and CSE grad students Erik Andersen and Yun-En Liu, teaches kids the principles behind fractions through snazzy graphics, compelling animation and a storyline involving cute alien babies, animals and laser beams. Players are asked to divvy up laser blasts into thirds, fourths, fifths and redirect them to power spaceships containing animals that have gotten stuck in space.

“Early math education is one area where students in the U.S. aren’t doing as well as they could be,” says Cooper. “And fractions are one of the concepts that students struggle with. By using games, we can hopefully get students involved and interested in math. But we can also learn from the students what kinds of approaches work. We can use that data to learn the optimal way to teach math and even adapt it on a per-student basis.”

Better business … and better health

The Center for Game Science isn’t the only department on campus where educational games are being developed. At the business school, they are taking the idea behind case competitions into a whole new dimension.

Last December, the Center for Leadership & Strategic Thinking at the UW’s Foster School of Business and Redmond-based online game developer Novel, Inc. partnered to create a series of business simulation games.

According to Professor Bruce Avolio, executive director of the Center for Leadership & Strategic Thinking, Novel will build the computer simulation; the Foster School will provide the knowledge as to what leadership and strategic thinking skills need to be incorporated, or what kind of scenarios should be included.

“Initially, there will be avatar-like characters, but downstream it will be more like 3-D virtual simulation, where the character is really in the game themselves,” says Avolio. “It’s not like Mario Bros. It’s very sophisticated, not just in terms of looks but in terms of the data you can put in, the number of people that can be involved.”

According to Avolio, these new Sims-style games will help both business students and prospective clients (and their employees) learn how to better interact in a business environment and respond to challenges such as mergers and acquisitions.

“Through their interaction and the way the game is set up, one can determine how aligned they are, how well they work together in terms of transparency or in terms of being goal-directed, how they go about making decisions,” he says. “To some extent, all that can be simulated, especially with leadership.”

Alaska Airlines has already signed up for the new product, offering some of its key strategic challenges as fodder for the game, which will function as a training tool for current and future employees.

“There have been a lot of people looking at games for kids with diabetes but nothing for adults. So we were looking at ways to fill that niche.”

Wanda Pratt, associate professor, Information School

“We’re really intrigued by this opportunity,” says Kelley Dobbs, ’05, vice president of human resources and labor relations for Alaska Airlines. “Having been through the executive M.B.A. program, I know there are fantastic business cases, but they’re static, on paper. You can’t get into the heads of what the leaders were thinking. Or know what the outcome would have been if they’d made a different decision.”

With these new business simulations, however, players will be able to test different decisions and scenarios in the virtual world in order to see how changes in strategy shake out in the real world.

“This will be another vehicle to add to the instructor’s set of resources,” says Avolio. “It’ll give people an idea of what it’s going to be like in business—and what they can do. Then they can reload and do the simulation again. It will give them an opportunity to practice, to build in efficiencies, before they actually go live in the workplace.”

The business of good health—at least for the country’s ever-increasing number of people with diabetes—is the purpose behind two other games being developed at the UW.

“There have been a lot of people looking at games for kids with diabetes but nothing for adults,” says Wanda Pratt, associate professor at the Information School and the Division of Biomedical and Health Informatics in the UW School of Medicine. “So we were looking at ways to fill that niche.”

Funded by a $200,000 grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Pratt and her team (which includes game developer UW grad student Lynne Harris) came up with two “casual-type” games which help people with diabetes understand the carbohydrate content of various foods in order to better manage their blood sugars.

In both games, players are asked to choose between two foods based on their carb value. Players who select the food with fewer carbs (for example, cup of ground beef over ¾ cup of watermelon or 1½ cups of carrots over one large apple) earn points. Enough correct answers unlocks another game where they can play Postcard—a trivia game—or a Sudoku-style game, which Pratt and her colleagues have dubbed “Foodoku.”

Both games have gone through one round of user testing and tweaks; Pratt says the next step will be to put the games—available either on home computer, or as a mobile-phone app—into the hands of people with diabetes.

“Our hope—especially with the mobile-phone games—is that people will play these games in the five minutes they have to kill while waiting for the bus,” she says. “They can do something to help their health and if they do that enough, it will make a difference.”

Whether it’s protein folding or fractions, figuring out the secrets to better health or better business, the UW’s advances in the world of educational games seem to be making some crucial differences—not to mention attracting a keen following.

“As a player, it makes me feel that there’s an actual purpose to it,” says PhotoCity devotee Emma Lynch. “I’m not just playing this to waste my time, there’s something going on here. I like that aspect of it and I like that idea. I’m interested to learn more about what other sorts of problems could be solved by playing games.”