On a quiet day in late June 1942, a few weeks after the UW’s commencement ceremony, a University of Washington dean slipped out of his office, got into his car and started to drive to Puyallup.

He had an important duty to perform, but this appointment was not recorded in official University records, nor can any account be found in local newspapers of that era. The dean may have wanted to keep his trip a secret. If word got out, there could be angry letters, raging editorials and perhaps a phone call from legislators in Olympia.

On the seat next to him was a stack of UW diplomas. Though there was a war going on and the campus would soon be packed with men—and some women—training for the military, the University of Washington had just lost more than 400 students. This official was on a trip to make a symbolic gesture to some of them.

The destination was the Western Washington Fairgrounds in Puyallup, but there were no amusement rides or animal husbandry exhibits that summer. Underneath the grandstands and in the stables that once housed cattle, thousands of local Japanese American families were gathered in an “assembly center” called Camp Harmony. Under Executive Order 9066 signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the military had ordered more than 110,000 Japanese Americans to leave their homes on the West Coast—including 70,000 who were U.S. citizens.

Japanese Americans register with authorities at the

Puyallup assembly center. Photo by Howard Clifford,

courtesy of UW Libraries, Special Collections, #UW 562.

For most of the UW students who were Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans), the order to leave came in May, before the end of spring quarter. Despite pleas from President Lee Paul Sieg and Arts and Sciences Assistant Dean Robert O’Brien, the Army refused to let Nisei students finish their studies before being sent to the camp. They had three or four days notice and then they were gone. Army officials demanded that Japanese American faculty also leave—even though most faculty members were American citizens (one was a veteran of World War I). Even faculty teaching Japanese language courses—crucial to the war effort—had to leave.

Because of the internment orders, the June ceremony at Camp Harmony lacked any of the pomp and circumstance traditionally found at a college commencement. There wasn’t much of a crowd either. The camp officials wanted to limit the audience, perhaps for security reasons. “All those who have graduated in the past fall or spring quarters will be allowed to attend,” the Army declared in a memo to the camp inmates. “All those of senior standing at the University of Washington will also be able to attend. Each graduate will be allowed to invite their immediate relatives and/or friends, approximately four each.”

“It was not a dress-up occasion,” recalls George Mukasa, ’42, one of the UW graduates who received his diploma that day. “I was there with a T-shirt on.” The economics major was the first member of his family to graduate from college, yet he can’t remember if his mother or three siblings were present.

Mukasa is fairly certain that Business and Economics Dean Howard Preston gave him the diploma. “They called my name and handed over my diploma and a graduation packet. It was very simple.” Other UW officials may have also attended the event. Letters in the UW archives suggest that Arts and Sciences Dean Edward Lauer and Registrar Irvin Hoff were there.

“I thought it was pretty nice. They didn’t completely ignore us,” recalls Mukasa. At the same time, he says the ceremony was “pretty anti-climactic.” There were so many other events over the past seven months—starting on Dec. 7—that seemed more significant.

Members of the UW’s Japanese Student Club relax in their living room in this 1941 photo. At the upper left, with his hand on the mantle, is Toru Sakahara. Photo courtesy UW Nikkei Alumni Association and Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project.

There is no record of any other college or university commencement ceremony at Camp Harmony. The UW was probably taking a public relations risk by holding even a simple event. But this gesture is symbolic of the University’s reaction to the idea of imprisoning Japanese Americans in the months after Pearl Harbor.

Before the decision was final, several UW officials testified against the proposal to send American citizens to internment camps. They then argued that their students and faculty should be exempt from the order. When that failed, they tried to find places at other universities for students willing to transfer—and got 58 out before they had to report to the camps. Student voices also opposed the internment. Editorials in the Daily defended Japanese American students and two UW undergraduates testified at a Congressional hearing against the idea.

These voices of reason were drowned out by racism and war hysteria, says American Ethnic Studies Professor Tetsuden Kashima. After Pearl Harbor, military and government officials feared a Japanese attack of the West Coast. They considered the Japanese American population a hotbed of sabotage and espionage.

“The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted,” wrote Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, the military official who ordered the internments. He added that there was “no ground for assuming that any Japanese, barred from assimilation by convention as he is, though born and raised in the United States, will not turn against this nation, when the final test of loyalty comes.”

Powerful media voices—including columnists Walter Winchell and Walter Lippmann—advocated internment. In addition, says Kashima, there was a failure of political leadership. Attorney General Francis Biddle and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover told President Roosevelt there was no need for the imprisonment of American citizens. “Even the Office of Naval Intelligence opposed the internments, Kashima says. But Roosevelt wasn’t listening.

***

On Dec. 7, 1941, Toru Sakahara, ’40, was a third-year law student at the University of Washington. Ever since he participated in a mock trial at Fife High School, he had wanted to be a lawyer. His father had a truck farm in Fife and Sakahara grew up tending crops of onions, beets, carrots, beans and peas. Though his dad had risen to become the manager of a Japanese farmers’ cooperative, Sakahara was not interested in carrying on the family business.

At that time, the UW had a six-year law program—three years of pre-law and then three years of law school. Sakahara moved to Seattle and stayed at the Japanese student clubhouse on 15th Avenue N.E. To save money, he spent one year as a “school boy,” doing housekeeping for a wealthy family near Golden Gardens Park. But the work was tedious and he returned to the clubhouse.

On that Sunday morning Sakahara was walking past the student lounge in the law school. A radio was playing louder than usual and he stopped to listen. Japanese warplanes had attacked the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. “It was a considerable surprise,” he says. “There had been talk about a war with Japan, so in a way it was not a surprise, but in another way it was a considerable shock.”

Back at the clubhouse, George Yashui, ’57, was in the kitchen. A junior in chemical engineering, Yashui was the son of an Olympia oyster farmer. It was messy and hard physical labor, and he couldn’t wait to join his two older brothers, who were already UW students. When he got to the University, he started having a good time. “If it wasn’t for the war, I probably would have failed,” he recalls.

Yashui also heard the news on the radio. “I remember yelling, ‘Those goddamn fools,’ to my brothers. We were stunned.”

Sueko Hasagawa Sumioka, ’45, ’60

Sueko Hasagawa Sumioka, ’45, ’60, was at the Japanese Congregational Church in the International District that morning. Her father was also a farmer in the Puyallup Valley. “After high school I spent two years working on the farm. I got tired of it. I was happy to get an education. Farm work was not for me.”

Sumioka found a job as a “school girl,” working six days a week as a maid for a family in Laurelhurst. Sunday was her only day off, and she usually went to church. On Dec. 7, word traveled quickly among the congregation, although the minister tried to conduct a normal service. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, I hope Japan loses. If the U.S. loses, we’re sunk. The Japanese would not treat us very well.’ ”

Seattle native Hiro Nishimura, ’48, had just graduated from Garfield High School and was a freshman in 1941. To make his way through college, he worked as a janitor and dishwasher at St. Mark’s Cathedral and went to Alaska in the summer to work in the salmon canneries. Like most local Nisei, he was a commuter student living at home. On Dec. 7 he went with his father on a social visit to a family friend. Once there, they found that the Japanese vice counsel was also present. “We were listening to the radio. When I heard the terrible news, I was in shock. It was traumatic. Suddenly the vice counsel stood up and said, ‘Oh, I’ve got to go back to the office,’ and left in a rush,” Nishimura recalls. “I thought to myself, ‘He has to go back and burn some files.’ ”

Nishimura immediately understood the impact the attack would have on his community. “We lived with discrimination and social prejudice. With this war, which was not our fault, we knew the implications,” he says.

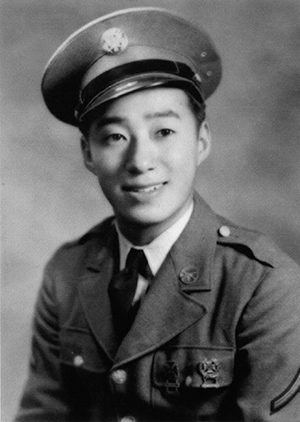

Hiro Nishimura, ’48, in his World War II uniform

That Monday morning, he considered skipping classes entirely. He decided to go to Suzzallo Library first, to test the reaction of his fellow students. “I felt all the eyes were upon me. I felt very, very self-conscious. But what could I do? You can’t turn white all of a sudden and become invisible.”

But there was no overt hostility. In fact, none of the Nisei students interviewed recalled any incident of prejudice following Pearl Harbor, even those who reported to the UW ROTC unit the next day. Sociology Professor S. Frank Miyamoto, ’36, ’38, recalls walking into his Introduction to Sociology lecture to a “warm reception” from his students.

That morning, if they picked up a copy of the Daily, Nisei students would find an editorial defending their rights. “We are at war. But when it is over, whether we are successful or not, let it not be said—as it can be said of students in the last war—that they were inflamed by the emotionalism of the mob and thereby diseased with intolerance. Let it not be said that we were too small of mind to respect the rights of man and the unfortunate Japanese Americans among us.”

***

In 1941, Japanese Americans were the largest minority group on campus. Japanese students had been attending the University of Washington since at least the late 1890s. In 1911, these students founded the Japanese Student Club and in 1922 they opened their own rooming house for men on 15th Avenue N.E., where the Social Work Building now stands. While they didn’t have a house, Japanese American women had a social organization, Fuyo Kai.

Both clubs took the place of traditional fraternities and sororities, which at that time banned all Asians and other ethnic minorities. But for many Nisei UW students, a social life was a luxury. When they weren’t in school, they lived at home and worked in the family businesses. Many needed help to attend college. In 1941, there were 45 Nisei students in a work-study program run by the National Youth Administration—about 10 percent of all UW students qualifying for this federal financial aid.

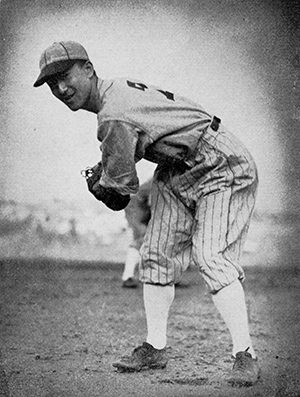

Joe Kesamura was a pitcher on the Husky baseball team

Some students felt isolated; others felt somewhat assimilated. Gordon Hirabayashi, ’42, ’49, ’52, (who would later oppose the internments and go to jail) was an officer in the campus YMCA, as was Kenji Okuda. Joe Kesamura was a pitcher on the Husky baseball team; Tad Fujioka, ’47, was on the varsity swimming team; and Frank Watanabe, ’44, was on the tennis team. The Daily had Dick Takeuchi as one of its beat reporters (he would later be the editor of a camp newsletter).

Cornell University Professor Gary Okihiro, who wrote a book on the fate of Japanese American college students during the internment, estimates that there were 3,300 Nisei attending college on the West Coast in 1941. No one knows exactly how many Nisei attended the UW that year. The best source is the 1941 Student Directory, which has 440 Japanese names, but that list is bound to have some errors or omissions. Other UW sources identify four Japanese Americans as teaching that year.

While these students were American citizens, their parents were not. Immigration law banned foreign-born Asians from becoming Americans. Since aliens could not own land, often family farms and businesses were held in trusts or owned by the eldest son if he was a citizen. “That their parents may be confined in a concentration camp while they faced discrimination and suspicion was held not impossible by many of the students,” the Daily reported on Dec. 8. The idea that the Nisei students themselves—all American citizens—might also be sent to concentration camps “didn’t cross our minds,” says Norio Higano, ’42. If the government would start rounding up Japanese, “we felt it would be the non-citizens,” adds Roy Inui. “We felt our civil rights would be respected.”

But the roundups were already starting. The FBI had a list of leaders in the Japanese community who were not citizens, and that night they started arresting them.

***

Toru Sakahara, the third-year law student, was worried. His father was on a business trip in California. But on Dec. 7, he disappeared. When the news reached him, Sakahara left the UW and returned to the family farm in Fife. “I don’t remember telling anyone at the law school. I just dropped out,” he says.

Then the sheriff in Yreka, Calif., reported that he had the family’s Buick sedan. Sakahara’s father had been arrested on the highway in northern California and sent to the Immigration and Naturalization Service in San Francisco. It was relatively dangerous for a Japanese American male to travel in the weeks after Pearl Harbor. Sakahara had to carry a birth certificate to prove that he was an American citizen. But he was determined to find his father.

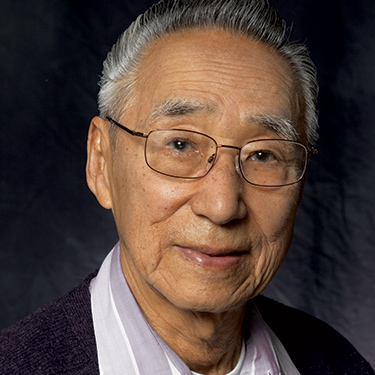

Toru Sakahara, ’40

He got on a bus to Yreka, picked up the car and then drove to San Francisco. While he staying with family friends, a nun called to let him know that Japanese aliens rounded up by the FBI were going to be sent to a camp in Missoula, Mont. She told him the time the train was leaving.

“I went to the train station and found my dad. Out of all the internees, he was the only one to have a relative come to see him off. Nobody explained anything. All I could say was hello and good-bye. I think he cried and I think I cried,” he says.

Back on the farm in Fife, Sakahara was responsible for six family members. Rumors spread that only aliens were going to be interned. Others speculated that everyone would be sent to camps—citizens and non-citizens alike. But Japanese American farmers had to act as if nothing was going to happen. “If the farmers did not plow and plant vegetables, they would be guilty of sabotage,” Sakahara recalls. “And if these crops were in the ground, maybe we would have a chance to sell the crops and get some money. So every day we went out and plowed and disked and planted.”

In Seattle, the situation was tense for Nisei students. The Friday after Pearl Harbor, Assistant Dean Robert O’Brien held a meeting. About half of all the Nisei students showed up in Home Economics (now Raitt Hall). O’Brien explained how the UW had already helped nearly 50 students get copies of their birth certificates to prove they were American citizens. Sociology Professor Jesse Steiner went over the curfews and financial restrictions suddenly slapped on Japanese Americans. “Representatives of the University are working in close cooperation with downtown churches and the Seattle Defense Fund to help solve the problems of the American-born Japanese students and their parents,” O’Brien said.

O’Brien would be a key player in the effort to keep UW students out of the interment camps and then to try to place them in other institutions. A Quaker who was a member of the sociology faculty, he was the adviser to the Japanese Student Club. He became President Sieg’s top aide on the relocation issue, later drawing heat from conservative groups who felt he should be fired.

Professor Emeritus Miyamoto recalls O’Brien as “not the greatest sociologist, but very warm hearted, very socially minded. Society needed to be better than it was and he would contribute to that change.”

Even before President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, O’Brien was already working on helping UW students continue their education elsewhere. He explained to pre-med student Norio Higano, for example, that his first year of medical school could count as his last year of undergraduate studies as well. “He told me, ‘Go ahead, try to get into medical school. See what happens,’ ” Higano says.

“It was almost impossible for Nisei to get into medical school,” he recalls. Only one took a chance on Higano, even though his grades were spectacular and he would graduate Phi Beta Kappa. He could start at St. Louis University Medical School in June, when, because of the war, its accelerated program was beginning. So in March, before the removal orders were final, Higano left for Chicago, where he would stay until medical school started. “I was able to continue my education flawlessly,” he recalls.

During this limbo period, Japanese American students weren’t sure what they should do when winter quarter started. “We decided that we’ll do the best that we can. We paid our tuition and if possible, we’ll continue our studies,” says Kenji Okuda, who was a sophomore that year and a close friend of Higano.

Professor Henry Tatsumi, ’32, ’35, continued to offer Japanese language courses and Miyamoto continued to teach Introduction to Sociology. He found no hostility from his students and no drop in enrollments despite the anti-Japanese rhetoric racing across America. “I have always thought of the University campus as a safety net for people who were likely to be badly treated elsewhere,” Miyamoto says.

Hiro Nishimura, ’48

For Hiro Nishimura, who watched the Japanese vice counsel leave in a panic on Dec. 7, the decision was made for him. He was drafted into the Army in February. “The Army came to my rescue,” he says. “It spared me the indignity of evacuation and internment. This was the same army that uprooted my family,” he says.

That same month, a rapid series of steps sealed the fate of Japanese Americans. On Feb. 13, the Pacific Coast Congressional delegation sent a letter to Roosevelt recommending “the immediate evacuation of all persons of Japanese lineage and all others, alien and citizen alike, whose presence shall be deemed dangerous or inimical to the defense of the United States.” Six days later came Executive Order 9066, authorizing the military to draw up proscribed areas where “the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose.” Two days after that, the Tolan Committee of the House of Representatives began to hold hearings on the need for mass “evacuations.”

At that point, the Japanese American Citizens League held an emergency meeting in San Francisco. Law student Sakahara, who had dropped out Dec. 8, was active in the league. One of his friends was a Chevrolet salesman and four league members piled into his car and drove to California.

“We were going to demand that American citizens be permitted to stay,” Sakahara recalls. As a bargaining chip, they would concede that Japanese Americans could be under military control—a moot point since the Army was restricting movements anyway. But when they arrived in San Francisco, the league leadership had other ideas. “We were told, ‘It’s no use. It’s already been decided.’ The discussion now was about resistance in the courts or to take part in whatever activity was necessary to evacuate,” he says. The league leadership was trapped. If they opposed internments, they would be accused of being unpatriotic or disloyal.

Back in Seattle, the Tolan Committee was wrapping up its Congressional hearings on what it called “national defense migration.” Five representatives from the UW testified or submitted written statements opposing the incarceration of Japanese Americans. Forestry Instructor Floyd Schmoe argued against internment. Another UW witness, Assistant Dean O’Brien, said, we should “trust our security to the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Military Intelligence” instead of imposing mass “evacuations.”

Sociology Professor Jessie Steiner gave a long account of Japanese immigration to America, ending with a defense of native-born Japanese Americans. “They are American citizens and a way should be found to safeguard their rights and treat them with justice insofar as this is possible in a war emergency,” he said.

One representative wondered what would happen if there was a Japanese attack on a Boeing plant. Steiner shot back, “I cannot see how our situation would be materially improved if we simply went ahead and got rid of all our Japanese, first and second generation, unless we took care of the Germans and Italians, also. Unless we did that, we still would have enemies, or potential enemies, in our midst. As to the second-generation Germans, we don’t doubt their loyalty. Why should we doubt the loyalty of second-generation Japanese?”

Two UW students showed up without an invitation to speak, and their testimony drew the only applause, according to press accounts. Curtis Aller Jr., ’42, a senior from the Yakima Valley, said, “I urge this committee to consider if we can even remotely demand or expect that these American citizens will remain loyal if instead of tolerance, we give them intolerance, mass hysteria and blanket condemnation? Can we ask them to believe in democracy if democracy does not believe in them?”

The words were eloquent but pointless. That same day, Lt. General DeWitt issued Public Proclamation No. 1 The western halves of Washington, Oregon and California were officially off-limits to anyone of Japanese ancestry.

“The Stolen Years” concludes in the next issue of Columns with a look at the struggles the UW faced in transferring its students, the story of Gordon Hirabayashi’s arrest for defying internment orders, and accounts of what happened to students forced into camps or schools away from the West Coast.

Many portions of his article rely on research by Theresa Mudrock, the history librarian for UW Libraries. For more information on this period in UW history, see Mudrock’s Web exhibit, “Interrupted Lives.”