Henry Victor Morgan was a popular Tacoma minister with an international following. His son Murray often accompanied him on speaking tours after the boy’s mother died in 1932. A fast, accurate typist since junior high school, he pounded out correspondence, his own and his dad’s, far into the night in hotels and on trains along the way. His occasional handwritten letters in his favorite green ink show his lack of practice with penmanship.

Murray was a lifelong agnostic. His dad once called him “a clod untroubled by a spark.” But church was the family business, and he helped out at services. In 1933, during a youth performance, he noticed a gangly 14-year-old playing the violin, badly. He introduced himself and found she was witty and cheerful as well as pretty. When he left for UW that fall, he and Rosa Northcutt started a correspondence that continued through their times apart for the next 70 years. Rosa was his official girlfriend by the time he boarded the train for Halifax, Nova Scotia, on June 14, 1936, hauling a portable typewriter and a letterman sweater borrowed from just-graduated Husky football guard Fred Gadke.

Murray wrote to Rosa nearly every day for the next three months. His letters reveal a sports-obsessed, Rosa-besotted, very young man. His attention to description and his interest in the characters they met on the trip are the clearest precursors of his later achievements as a journalist and historian.

After a stop in Montreal, Murray and Henry Victor boarded the HMS Ascania for England.

The HMS Ascania from the Cunard Line displays impressive size in this postcard.

Sunday, June 22, 1936, 11 p.m.: Dearest Rosa, Belle Isle lies behind us now, hon, and all there is ahead is six days of open sea and England—I’ve been thinking about you an awful lot today, sweetness. The air is cold outside—we are north of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and just off of the coast of Labrador. There are icebergs all around us and the boat is rolling so much that it feels we are on horseback but travelling in a slow motion—I can’t describe it. Sunset tonight was another indescribable experience. We were just passing Belle Isle when the full splendor of it struck us. The sun was cut in four parts, which split its surface irregularly but were stained crimson by its glorifying rust. The sky was red, shading deeper toward the ground. Then an abrupt halt on the cold dark slate of the island. Color again—green water and two white icebergs with edges reflecting crimson—green water and foam—the sunset lingered but I went below. It was too beautiful to stand, alone.

Once in London, the first stop on the lecture tour, they began to search for tickets to the Olympics and lodging in Berlin. Although American participation in the Games was controversial, Murray didn’t mention that in his letters. He was more concerned about the state of his romance, writing to Rosa on July 29:

Murray’s ticket to the opening ceremonies of the Berlin Olympics cost 10 Reichmarks.

The two weeks or more space that it takes to get and send letters makes you seem horribly far away, darling. I get a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach every time that I allow myself to think of it, which is most of the time … At night I dream about things happening to you that I can’t prevent and I don’t get any too much sleep.

He did, however, write to his best friend and UW classmate Frank Sadler about the British state of mind.

“… the problem of politics in Europe and the possibility of another war is no longer something to be viewed in the abstract. In Washington, it seemed that war would come out of the antics of European statesmen, that America would be drawn in, that we would go over and get shot at, and so what. Here in London, war is something far from intangible. On the contrary, the country and people are busily girding themselves for the reality of torn flesh, darkened cities under the wings of bombers, and subways crowded by people trying to escape gas.”

Then he switched back to what his fellow UW Daily staffers referred to as “the Rosa project.”

Enclosed you will by now have discovered a couple of dollars. Will you please buy some roses, carnations or gardenias for Rosa?

Other letters focus on Murray’s frustration with the lack of American sports news, particularly the outcome of the Olympic crew trials in Poughkeepsie. He was desperate to find out if the Huskies were bound for the Olympics. Thanks to a well-connected friend of Henry Victor’s, they secured passes to the Games, including the opening ceremony, all track and field events, all crew events, and boxing for Murray. They paid about $35 per person.

German sprinter Fritz Schilgen carries the torch to open the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

After speaking engagements in Liverpool and Scotland, followed by a week in Paris, they took the train to Berlin, which was scrubbed and sanitized for the Reich’s PR opportunity. American reporters described the scene with foreboding. Grantland Rice wrote in The Los Angeles Times that the entrance to the stadium on opening day was “seven massed military miles rivaling the mobilization of August 1, 1914. The opening ceremonies of the eleventh Olympiad, with mile upon mile, wave upon wave of a uniformed pageant, looked more like two world wars than the Olympic Games.”

Murray was more concerned with news from Rosa, who was working that summer at Tacoma General Hospital. A high school friend had his appendix out, and she went on a bit about his bravery and her delight in caring for him. She also announced her decision to study nursing rather than start at UW in journalism the next year as she and Murray had planned. In five single-spaced pages devoted to talking her out of the switch, he had just a few words about the pageantry of the first day.

Yesterday was the opening of the Games, and it was really impressive despite the threatening skies that gave occasional splattering hints of what it could do and despite the fact that I was feeling really blue. To me the high spot was the runner carrying the torch which had started in Athens and had been brought by relay all the way from there. The runner was a picturesque blonde with much grace and good acting ability who lit the big torch at the end of the Stadium with a flourish of grace.

His romantic worries were compounded by lack of compatible company.

Dad has one of his old students over here and she insists on taking us around a lot. We hate each other quite heartily, she being an ardent Hitlerite and I not being quite so enthusiastic, she being Republican at home and I being Democratic, she hating the books I love and vice versa. So now I walk out to the Olympic Stadium, five or six miles away, to avoid her as much as possible.

Clad in a letterman sweater borrowed from just-graduated Husky football guard Fred Gadke, Morgan looks spiffy on the deck of the HMS Ascania en route to Europe.

Murray wore his borrowed UW letter sweater on these walks, leading many locals to assume he was a foreign athlete. Lacking much German and enjoying the attention, he signed a variety of autograph books as “Merritt E. Benson, weight-lifter, South Africa”; “Byrdon Walter Gadke, rope-skipper, Australia”; “Dr. Karl Sarpolis, coxswain of the crew, U.S.A.,” and a few more. It’s much easier to sign than it is to explain…

Another solace was reading.

Our hostess, Mrs. Lewald, is a German authoress who can read English and has a few English books around. She lent Dad a book to read which he didn’t like, so I decided it must be good. I started to read it and it kept me up till way past twelve to finish it at one sitting. The name is Lost Horizon …

Once the Games turned from choreographed parades to competition, and Rosa wrote to reassure him, he felt better, reporting his observations on the proceedings.

There wasn’t much phoney work pulled at the track and the events which were a little bad were obviously not intentional discrimination, but elsewhere, the same cannot be said. In one of the bike races a German committed a few fouls on a Dutch rider and when he came in first was not disqualified but instead fined 100 marks. Figure that one out in amateur sports.

The worst though is the boxing. There the crowd yells itself hoarse every time a German throws a punch whether it lands or not. The judges evidently go by noise made, for although I’ve seen Germans lose at least six bouts by varying margins, only two have dropped decisions. Furthermore the Americans and Argentines have been robbed hog wild on some of the decisions. The prize last night was a fiasco in which Clark, a negro, was given the bout on a foul but wouldn’t take it. He went on to floor his man three times in the last round and then lost the decision. And the crowd cheered.

Although his passions were boxing and crew, he was thrilled as anyone by the other American achievements.

American runner John Woodruff.

I’ve had a swell time at the Stadium, watching the American “black and whites” monopolize about half of the track and field titles.

He saw all of Jesse Owens’ victories, calling him the “sepia-colored sprinter” and “quite a lad.” He was especially thrilled by the final 400-meter relay, in part because he had seen the Americans set a world record of 40 seconds in that event at the previous Olympics in Los Angeles. “The sports writers said it was impossible to improve on such running,” he remembered.

Yesterday I sat in another Olympic Stadium, tense as Owens, Metcalf, Draper and Wykoff lined up to run the relay for America. The day before, running the heats, they had tied the old world record … Today—with perfect running and fair baton passing they ripped around the track to the accompaniment of a roar from the crowd that was almost tangible. The time? A new Olympic and a new world record, 38.8 seconds. The sports writers say it is impossible to improve on such running.

Another negro, John Woodruff, a giant freshman from the University of Pittsburgh, was my next biggest thrill. He runs the half mile (800 meters) but the way he does it is the kick. His stride is gigantic, enormous. He simply seems to step around the track in about ten big efforts—yet efforts is not the correct word for his movements are graceful and easy.

Of course, the most personal event for any Husky was the eight-man crew final in the Husky Clipper at the end of the Games. The Morgans sat by the finish line, and on the trip back to England, he wrote a summary:

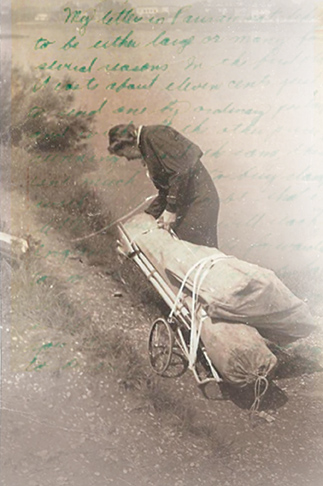

Murray and his new wife, Rosa, traveled to Europe following their wedding in 1939 to kayak down the Danube River. Rosa hauls the boat for their first day on the water in this photo.

I can see eight white blades biting into slate gray water, throwing great chunks of the river back as they hit and driving a thin shell faster and faster and faster towards the finish line. I can hear 80,000 voices chanting Deutschland in unison with the stroke of the German shell, and can feel myself shouting for Washington to “Hit it! Hit it! Hit it!” A long pause. Number 19 on the scoreboard. And the Washington crew rows by with laurel wreaths on their heads.

Once back home, he talked Rosa back into following their journalistic plans. She overlapped with him for a quarter at UW in 1937, working as his secretary at The Daily. He graduated that June, skipping the ceremony to start his new job in Hoquiam on the Grays Harbor Washingtonian. They married on March 5, 1939, in his dad’s church, and caught a freighter for Europe that same morning. Once again, Murray packed a portable typewriter.

Their plans, breathtakingly naïve given the times, were to buy a kayak and paddle it down the Danube from Bavaria to the Black Sea, reporting and photographing as they went. They almost made it. In a thousand miles on the water, they slept in haystacks when hostels weren’t available and sneaked eggs from under farmers’ chickens, leaving coins by the nest. Murray wrote travel articles and more letters, to his worried father and friends back home. Then, a few days from their destination, Germany invaded Poland, and they were briefly jailed in Giurgiu, Romania, as suspected spies. A few days later, they were on a train, which took nearly a week of increasing chaos to circumvent Germany on the way to Rotterdam and another freighter home. The days of oblivious adventuring were over.