Diversity in UW Law’s classes—125 years ago Diversity in UW Law’s classes—125 years ago Diversity in UW Law’s classes—125 years ago

The UW School of Law’s first class included a student of African-American heritage, a Japanese student and three women.

By Hugh Spitzer | March 2025

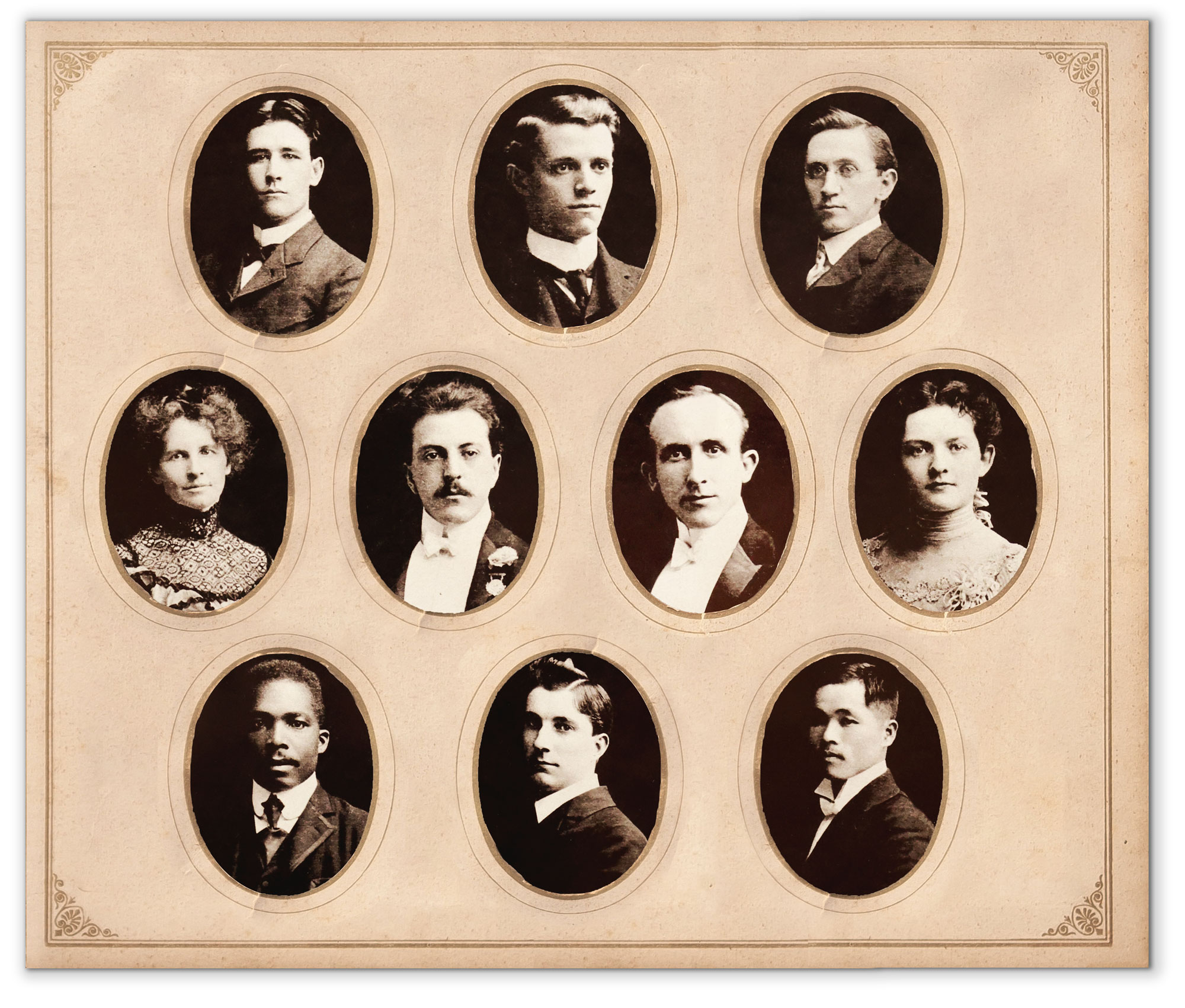

In 1901, a photo of 10 of the University of Washington’s first law students (below) shows a much more diverse group of people than one might expect at the turn of the century. At the time, Black Americans could not join the American Bar Association, and in many states, married women could not practice law because they could not form contracts without their husbands’ consent.

But because of our state’s commitment to equal education rights for all residents, a diverse selection of young Washingtonians could study law at the UW. And they excelled. Once they received their degrees, though, the members of this class who weren’t white and male encountered substantial challenges in establishing legal careers.

William McDonald Austin, pictured on the lower left, was a native of Barbados and a popular student who was elected class treasurer. His senior thesis focused on the Civil Rights Act of 1866. He became the first African American to earn a UW law degree and passed the Washington Bar with a high score. But unable to find employment in Seattle, in 1902 he left for the American-controlled Philippines.

Takuji Yamashita, on the lower right, was a Japanese citizen and star student who wrote his thesis on the head of the family in Japan. His motto in the 1903 Tyee Yearbook was Amicus Alienus (foreign friend). Though he had many friends in the U.S., Yamashita encountered barriers throughout his life. In 1902, Washington’s Supreme Court rejected his application to practice because of his Japanese citizenship. State law banned anyone but U.S. citizens from the bar. At the same time, federal law prohibited most Asians, including Japanese, from becoming citizens.

Yamashita turned instead to business. He opened restaurants and hotels and later farmed berries and harvested shellfish—and offered legal advice to friends and neighbors. Sent to an incarceration camp during World War II, he and his family were unable to make payments on their farm in Silverdale and lost it.

In 2001, the state Supreme Court posthumously admitted Yamashita to the Washington State Bar, acknowledging the wrong nearly a century after his UW Law graduation.

Adella Parker, center left, went on to practice law in Seattle, teach civics to high school students, fight for women’s suffrage and address corruption in city government by leading a successful campaign to recall the mayor. She served in the state Legislature from 1935 to 1937.

Two other early UW Law alumnae, not in the photo, went on to make history. Bella Weretnikow completed her first year of law school while finishing bachelor’s degrees in political science and social science, with honors in German. She was in the law school’s first graduating class in 1901 and became the first Jewish woman lawyer in the state. But she left the practice when she married a lawyer from Tennessee who had read about her law school graduation in the American Israelite newspaper and moved to Seattle to woo her.

Othilia Gertrude Carroll joined her family’s law firm. She also edited the Pacific Catholic Journal of Law and served as a local judge during World War I. She later established the first small-claims court in the state. In 1904, Carroll married Walter Beals, one of her UW Law classmates. He became a King County Superior Court judge and chief justice of the Washington State Supreme Court. He also served on the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg in 1946.

The UW School of Law has maintained its commitment to diversity and worked to reduce the obstacles that some graduates faced 125 years ago. The school has continued to graduate men and women of many backgrounds who have served the state, the country and the global community in a remarkable variety of ways.