Rooted in resilience Rooted in resilience Rooted in resilience

The UW’s Champions Program offers students who have been in foster care or experienced homelessness the foundation they need to grow.

By Caitlin Klask | Photos by Matt Hagen | Viewpoint Magazine

When Kip Howell, ’24, received his acceptance letter to the UW, it should have been a moment of celebration. A standout art student with impressive grades, the Seattle Central Community College transfer should have been looking forward to his time at Washington’s flagship university.

Instead, Howell, who had been housing insecure, was stressed. He was at the beginning of what led to six months in administrative limbo trying to prove that despite not having a stable address, he was a Washington resident. In-state tuition—the only way he could afford the UW—hung in the balance.

Fortunately, a fellow classmate who’d also experienced homelessness was able to guide him through the process. And then he found the Champions Program, a little-known but life-changing support system for UW students who have been in foster care or have experienced unaccompanied homelessness. Since 2011, the Champions’ small team has helped these students not just survive college, but thrive by connecting them to resources and offering community, guidance and advocacy.

Kip Howell returned to campus this summer and visited with counselor Cierra Draper-West, ’20, ’22.

At a university where wealth and stability are often the norm, Champions, which operates within the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity, serves students who arrive with little to no safety net and often no one to help them navigate higher education.

For Champions-eligible students, just getting into college is a major accomplishment. But staying enrolled is even harder. Nationally, the high school dropout rates for youth who have been in foster care are as high as 50%, and fewer than 5% earn a college degree, according to the National Foster Youth Institute. And the barriers, like housing instability, financial insecurity, trauma and a lack of family support don’t disappear after admission.

“We know each student will come in with their own things going on. And we never say, ‘We’re not going to help you with that,’” says Cierra Draper-West, ’20, ’22, the lead student coordinator for the Champions Program, and someone who brings her own lived experience as a former foster youth.

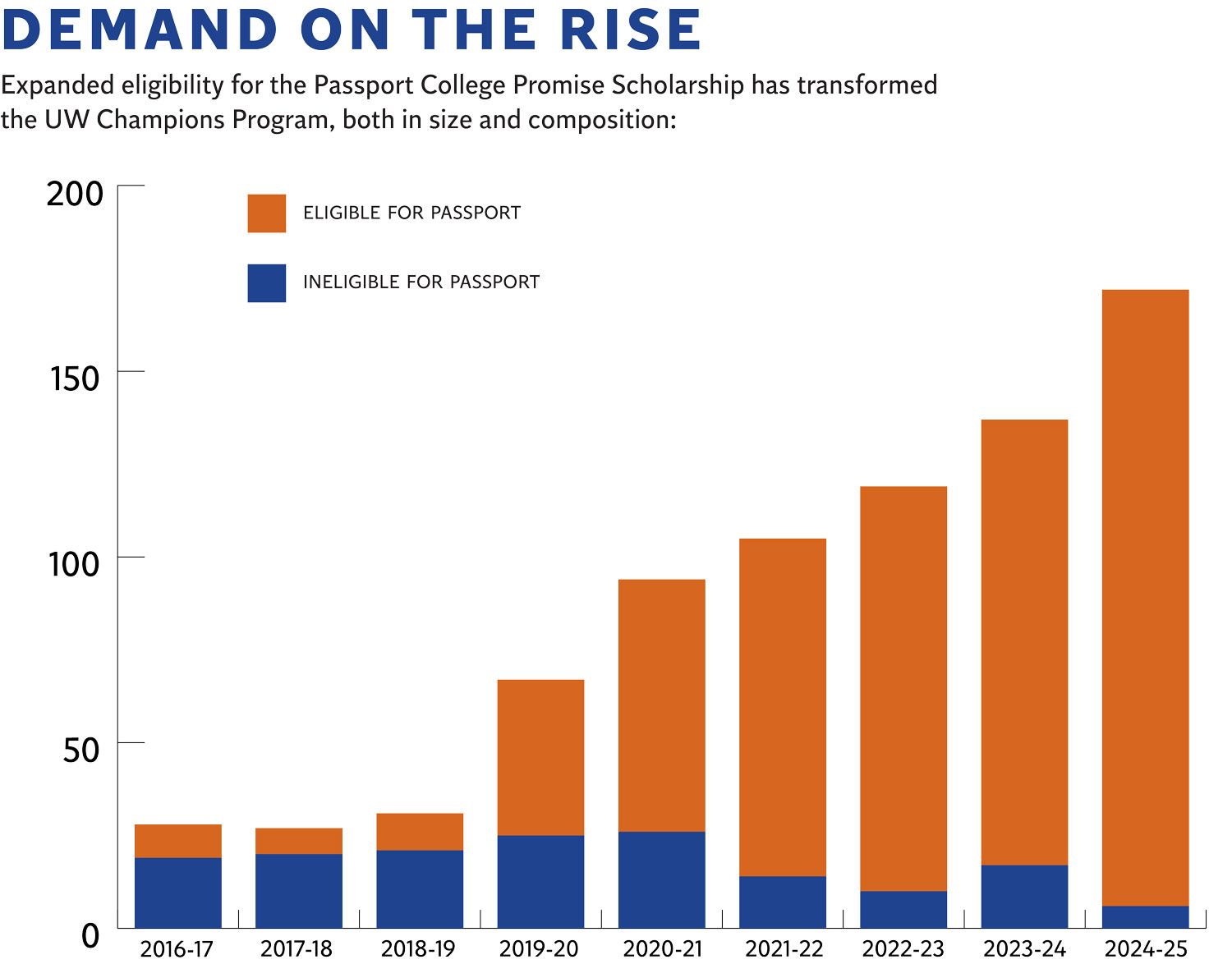

Draper-West and colleague Luana Coberg check in on every student in the program at least once per quarter. It was manageable in 2011, when the program had one staff member and served about 25 students. By 2019, the number of students had increased to 67. In 2024, it surged to 172 with three staff members on board. And this year, the student count is nearing 200, says Melissa Raap, ’11, who helped launch Champions as a retention specialist and today serves as its director. “I felt that 25 students were a lot; 100 per staff member is too much.”

“We are definitely at maximum capacity, and we need to make decisions about how we’re moving forward,” Raap says. The Champions Program’s growth has paralleled state-funded opportunities. The Washington Student Achievement Council now offers the Passport to College Scholarship for qualifying students who have been in foster care or experienced unaccompanied homelessness. It can cover tuition, fees, books and other college-related expenses, as well as fund holistic support services. In 2018, 10 UW students were eligible, having been in foster care for at least one year after their 16th birthday. By 2019, the scholarship rules expanded to include foster care at any time after the student’s 13th birthday, and 42 UW students were eligible.

Now, students who have experienced unaccompanied homelessness are also eligible for the Passport scholarship, which brings the UW number to 166. Champions, however, serves students who have been in foster care at any point in their lives, including out-of-state and international students.

Each fall, the Champions team receives a list with the names and contact details for students who have indicated a history in the foster care system or of unaccompanied homelessness. Champions also receives data from the Washington Student Achievement Council. Armed with that information, Draper-West and Coberg personally call each student to introduce them to the program and offer their support.

“A lot of times, they don’t know what they don’t know,” Coberg says. “I have a checklist: Where are they going to live? Do they understand how financial aid works? Are they meeting their basic needs? How do they feel about coming here?”

The first in-person event of the year is called First Day Bagels, Donuts & Coffee, a low-pressure gathering where students can connect with the program and meet other students with similar experiences.

For students, the Champions Office can be a safe space. “The Champions office feels like home,” says one student participant. “I can show up, no matter how good or bad the day that I am having is, and just exist with other people who get how I feel.”

“This is a big campus, but you can feel really alone here, especially because there’s so many people with wealth and nuclear families,” Draper-West says. “There’s Family Day. It’s not Bring Your Best Friend Day.”

The Champions team is personal and hands-on. They accompany students to the financial aid office, the counseling center and on-campus events. But that level of care is difficult for a small staff with a growing population to serve, especially when many students are not used to asking for help.

“Particularly, a lot of our students who have been in foster care, they want to be the ‘good kid,’” says Raap. “They’re struggling, but they’re not going to talk about it. It takes a lot of unlearning, but with us they can be more real.”

“The Champions office feels like home. I can show up, no matter how good or bad the day that I am having is, and just exist with other people who get how I feel.”

Champions Program student

Meanwhile, the Passport Scholarship, which provides student support funds for the UW, UW Tacoma and 46 other colleges statewide—did not sufficiently increase its funding for the 2024-2025 academic year, despite the rise in eligible students.

Raising support through philanthropy presents a challenge, as well. “People love to buy gifts for students, but it’s really hard to get people who want to fund staff,” Draper-West says. One reason is that the program won’t use student stories to tug at donor heartstrings. “We don’t ask students to speak to donors. We don’t bring donors in to see our events,” she says. “This isn’t a movie; these are real people’s lives.”

“There’s unsolicited pity that you get a lot, and it makes people not want to share their story,” she adds. That reluctance to share could also be about self-preservation. Raap recalls being told that students in the Champions Program often demonstrate lower self-esteem than other marginalized groups. “There’s a lot of imposter syndrome, or just opting out from things because they don’t feel like they can do them, or they’re scared of failing and embarrassing themselves,” she says.

“Every single student in the Champions Program has a different story,” Raap says. “I can’t say that if you’ve been in foster care, I know what you’ve been through.”

Kip Howell, ’24, who was unhoused before becoming a student at the UW, found support in the Champions Program.

For Kip Howell the Champions Program was a source of newfound self-esteem. After graduating, he landed a job with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Though he was laid off amid federal budget cuts this year, he remains hopeful about finding the next step in his career and is looking for new ways to combine his passion for art with his science experience.

“My path getting to where I am now, it was a very difficult one. I became homeless midway through high school,” he says. “The one thing I would want people to know is that you can be successful, even in difficult circumstances.”

That is why programs like Champions matter so much. “I would have a lot of doubts, and having somebody back me up, somebody who’s been in the same situation, definitely helps.”

Today, an estimated 42,000 Washington children are experiencing homelessness, and nearly 5,000 are in foster care. Black and Native American youth are over-represented in the foster care system, and LGBTQ+, though under-counted, are disproportionately affected as well.

With higher risks of addiction, mental illness or death by suicide, even attaining a high school diploma is a major feat for these young people. Graduating from a four-year university like the UW takes tenacity and support.

“It’s hard not to lose hope sometimes,” says Howell. “I think that’s why I spent my summer travelling after I lost my job. I made the most of an unfortunate situation.”

He visited friends, took an immersive glass art workshop and created pieces this summer that are part of a group show in Tacoma this fall.

Like many program alums, he stays in touch with the Champions team. In September, he stopped by the office in Mary Gates Hall to catch up with Draper-West.

“They’re so badass, and I feel really lucky to be in their lives and get to see them grow,” Draper-West says of the students. “Seeing them learning their strengths and love themselves is one of the most rewarding things. You see them blossom to this person they were meant to be.”