Being an artist was not the career Patti Warashina’s parents had in mind for her when she was growing up in Spokane. Her father, a Japanese immigrant, and her second-generation Japanese American mother encouraged Patti and her two siblings to take their education seriously so they could find careers that would support them as adults.

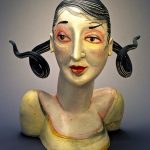

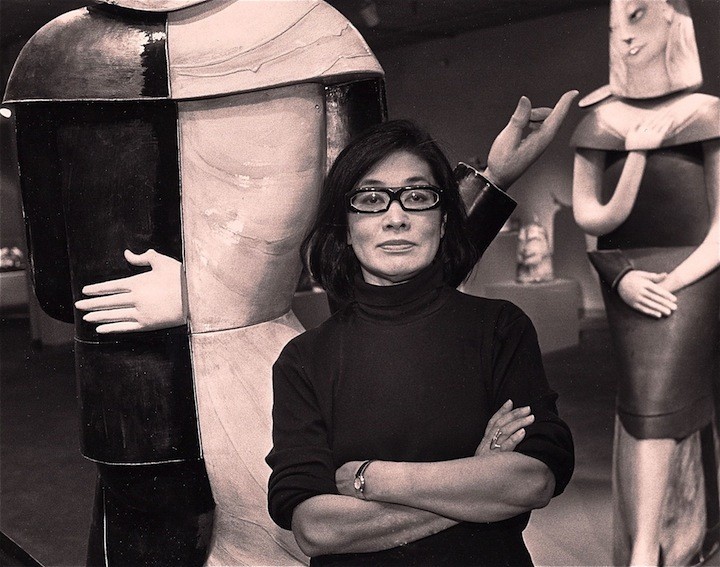

Warashina on the cover of the March 2020 edition of UW Magazine.

Warashina enrolled at the UW intent on becoming a dental hygienist. However, one day she took a required elective in beginning drawing. It captivated her and compelled her to take more art classes, which ultimately introduced her to the material of clay. That did it! Luckily, she switched majors and went on to become one of America’s foremost ceramic artists.

Now 80, Warashina, ’62, ’64, continues to create satirical and humorous figurative sculptures that explore the absurdity and foibles of human nature, as well as feminism and other political and social topics. The UW art professor emerita is revered by generations of ceramic artists and collectors. She will be honored in April in Washington, D.C., as the 2020 Smithsonian Visionary Artist.

In announcing the award, Nora Atkinson, the curator-in-charge for the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, describes Warashina as being “a defining figure in the West Coast Funk Art movement during the 1960s and 1970s, and one “who has been known throughout her long career for her mischievous figurative sculptures and tableaux.”

Atkinson says the artist uses humor and social commentary “to address serious personal, political, and social subjects, from feminist critiques of the art world, to the internment of the Japanese during World War II, to the absurdity of contemporary social media.”

One example of Warashina’s work is her 1971 “Convertible Car Kiln,” currently featured in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery. Selected Warashina sculptures will also be on exhibit in the National Building Museum at the 2020 Smithsonian Craft Show.

According to the Smithsonian Craft Show, the Smithsonian Visionary Award is presented annually to artists who have reached the pinnacle of sculptural arts and design, who have works in major museums, and who have demonstrated distinction, creativity, artistry, and vision in their respective medium. Previous Visionary Artists include Wendell Castle; Albert Paley; Toots Zynsky; Dale Chihuly, ’65; Faith Ringgold; and Joyce J. Scott.

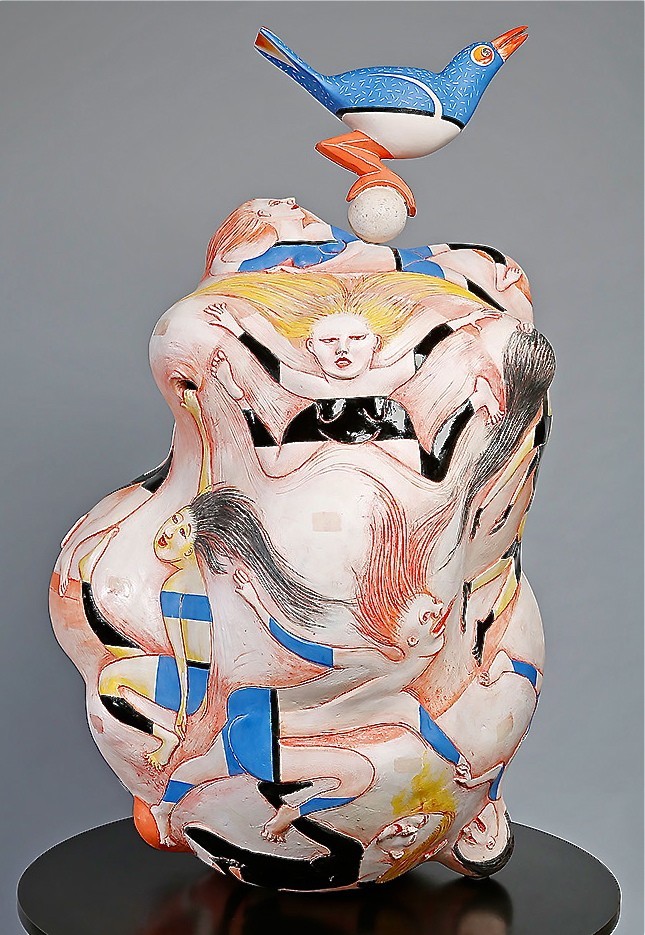

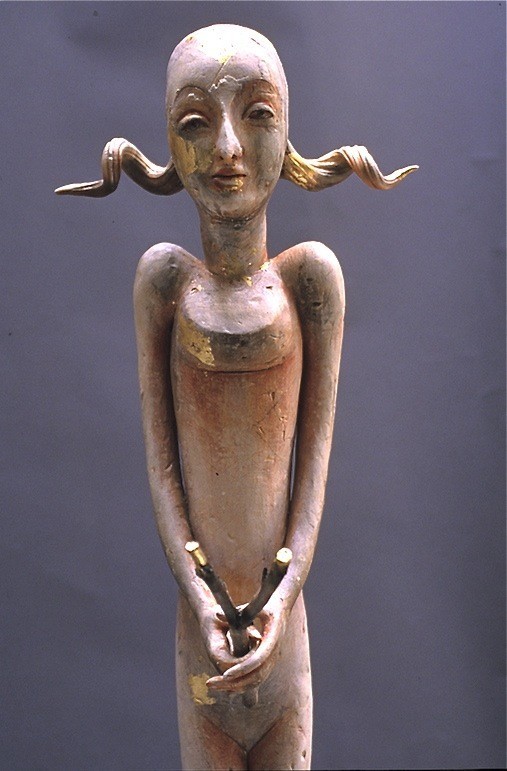

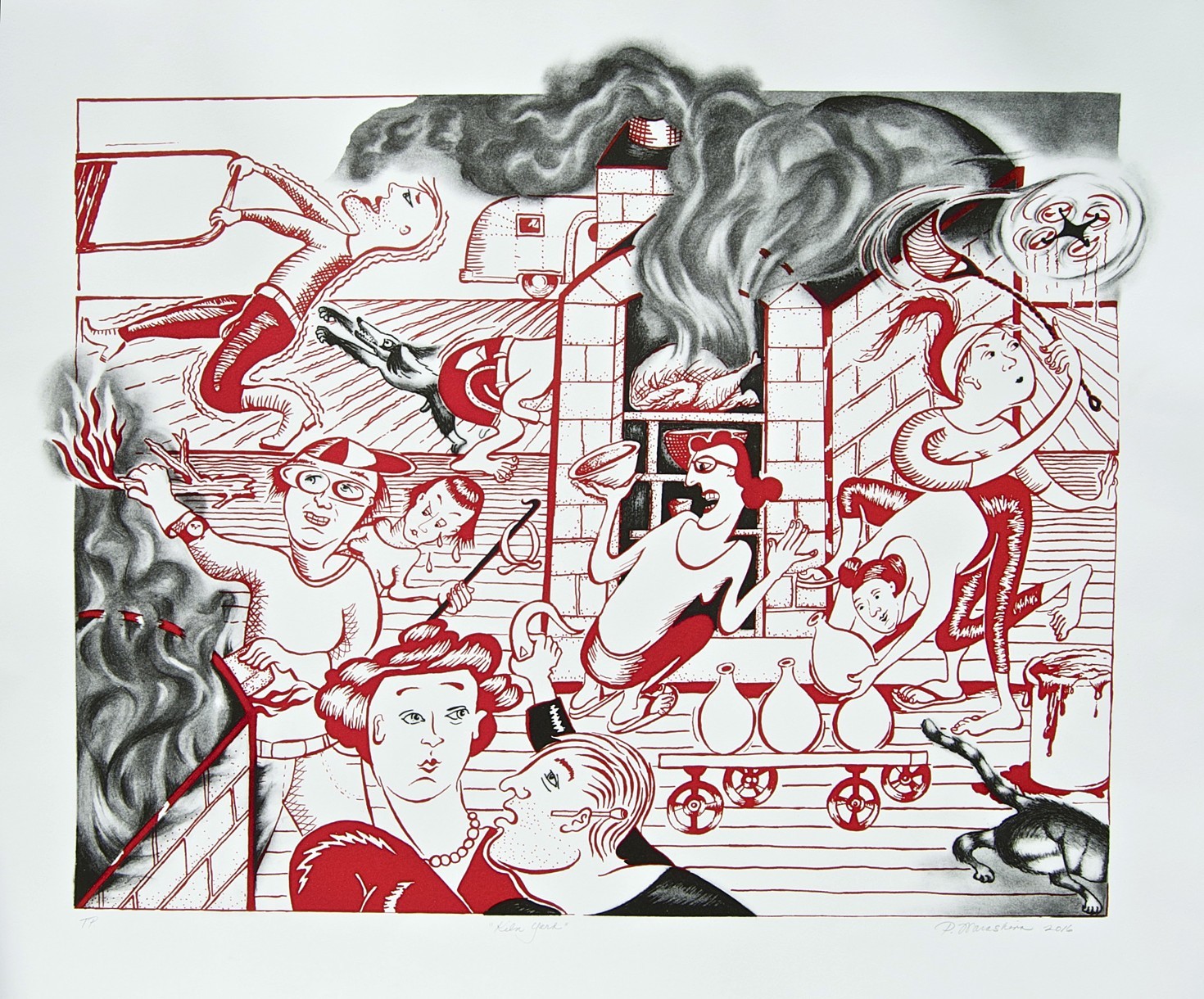

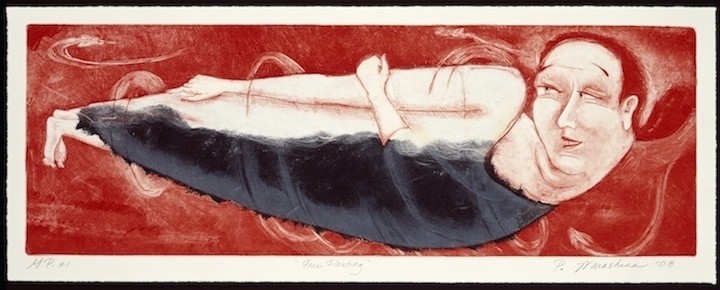

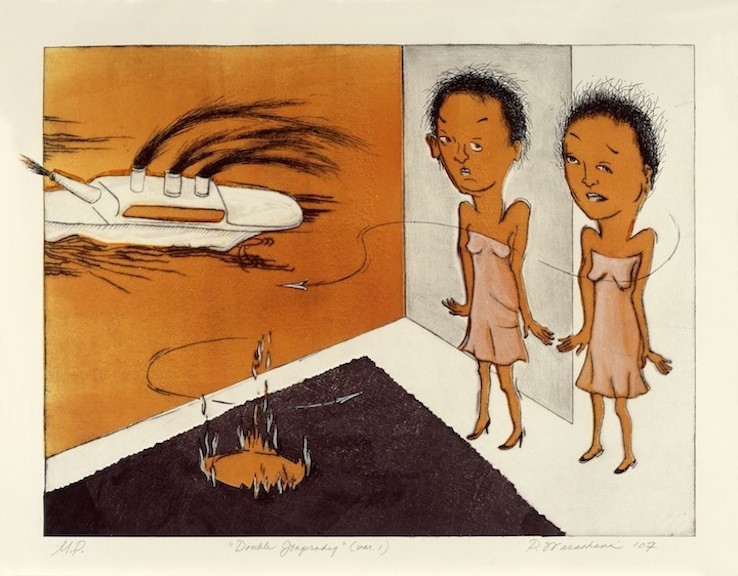

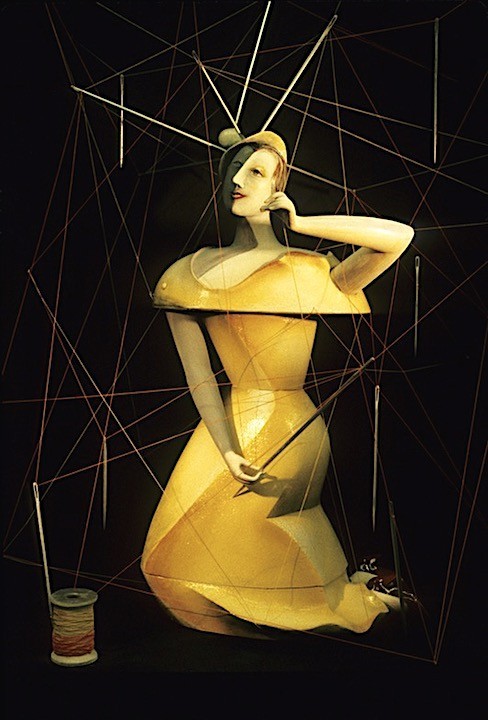

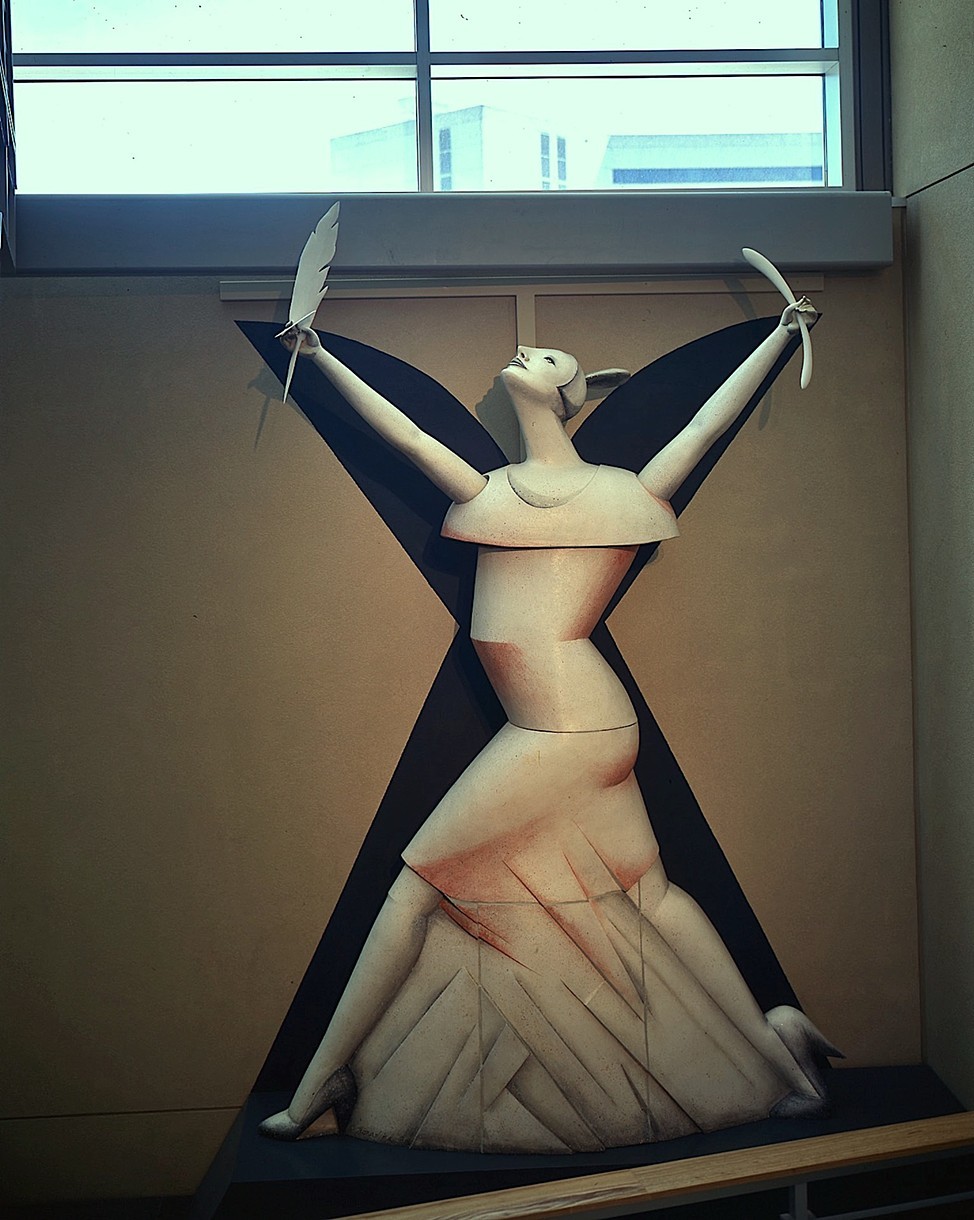

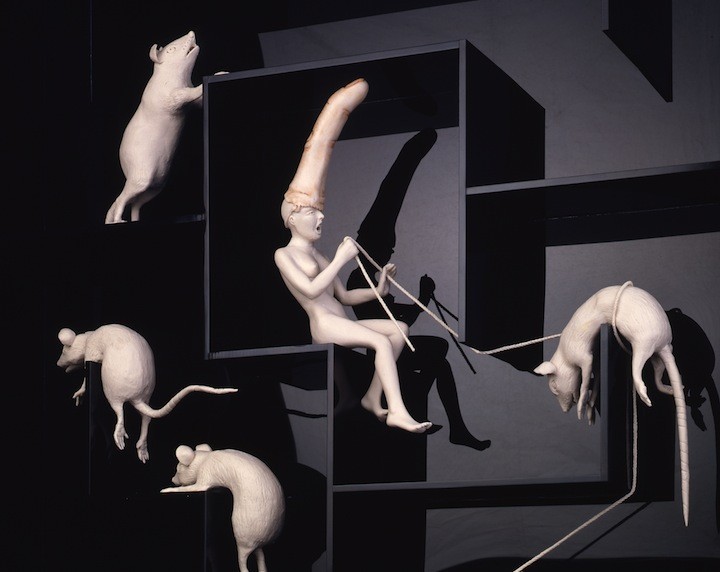

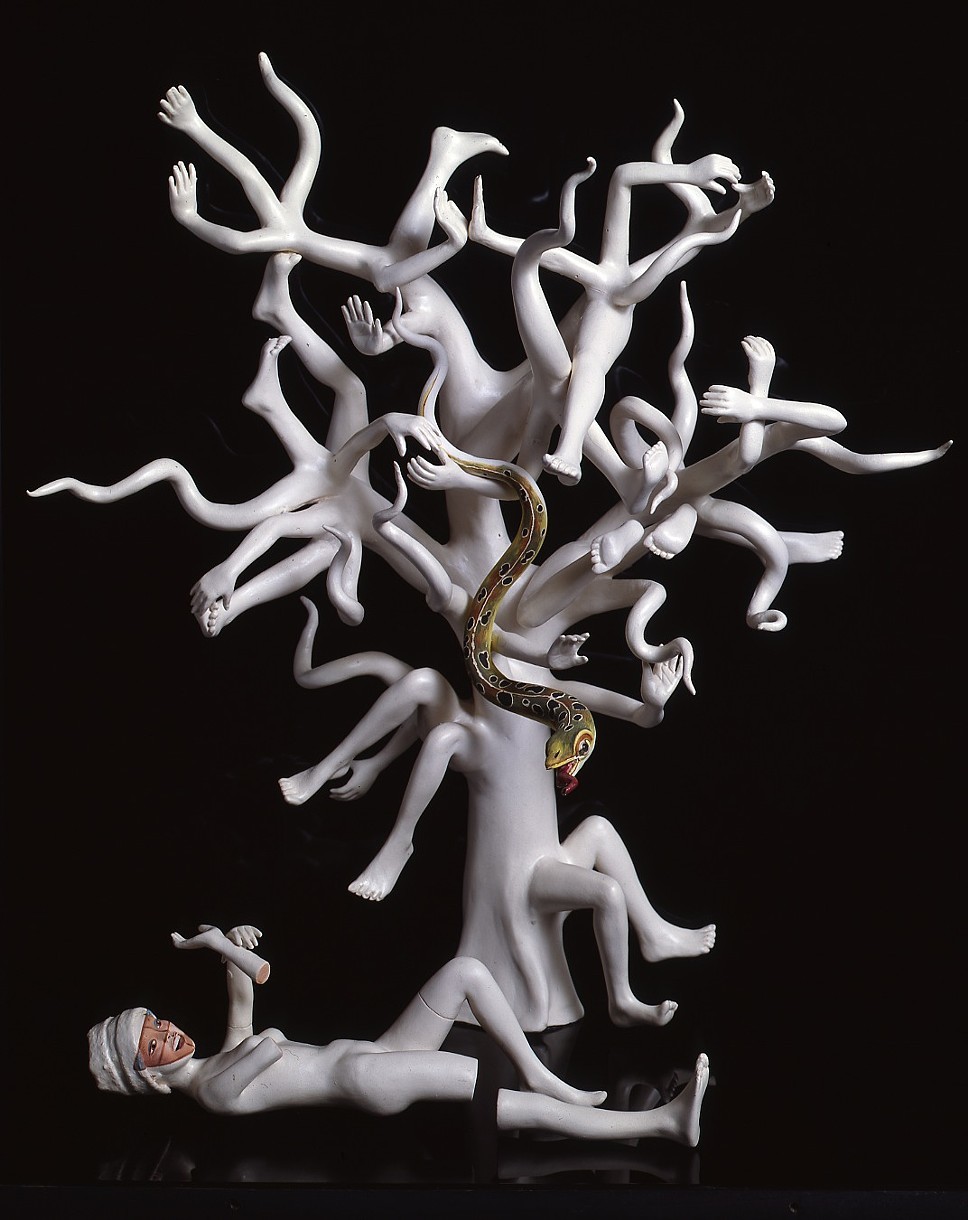

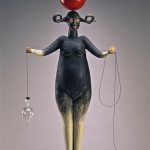

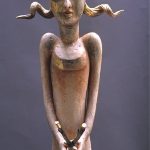

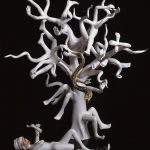

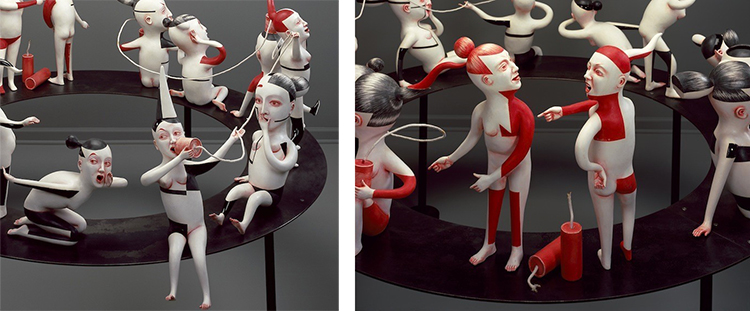

“Gossipmongers,” a mixed-media work by Patti Warashina, 2010.

Detailed views of “Gossipmongers.”

UW Magazine (then Columns) interviewed Warashina for a feature in 2007 when she was a faculty member in the highly ranked ceramic arts program. Here are some excerpts from that discussion:

You were born in 1940 and grew up in Spokane. Did you have any desire to become an artist growing up?

None. My dad, who was first-generation Japanese American, felt that women should be educated, which was unusual for that time. He was a dentist and always felt that you should have something where you could earn a living. So we were programmed to go into the sciences. I was supposed to be a dental hygienist.

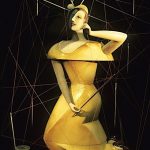

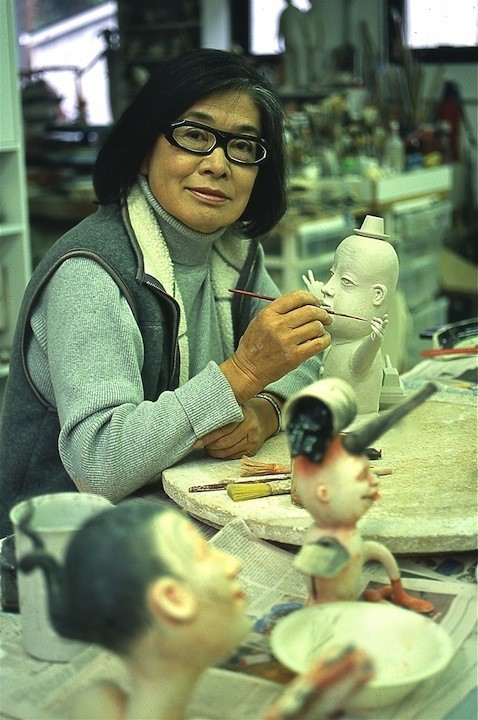

Warashina in her studio. Photo by Daniel Berman.

You came to the UW in 1958. What was it like? Did you want to join a sorority?

It was a conservative place. Women went to college to get married. Sororities? As an Asian, you wouldn’t even consider it. It was totally Anglo …. You kind of knew your place.

It’s quite a jump from dental hygiene to ceramic arts. Sophomore year I had an elective so I took a drawing class. I was really afraid of that class. People had art classes in high school and I had nothing. I didn’t even know what a charcoal stick was. But I just loved that class. When I took my first clay class, it was just mesmerizing. The material was really captivating. It also was a challenge learning how to throw on a wheel.

But you were still planning to be a dental hygienist?

Yes, I was still on that track. I took art classes because I liked them. Finally my adviser said, “Patti, just face it. Do it. Transfer over.” So I did.

When you were a student, Abstract Expressionism was the rage. Yet your pieces are based on the figure.

I never took any figure classes at all. It wasn’t cool. But the artists I was attracted to at that time—Magritte, Duchamp, other surrealists—were figurative. They were dream states. I liked the humor. I liked the ridiculousness. It’s just the way I saw the world.

You once said you have to be a masochist to be a ceramic artist.

Ceramics is a difficult medium. Not only do you have to paint the surface, but you have to know how to build. It’s very technical. Why would anybody in their right mind deal with a material that is so difficult? It can crack at any stage of the game. Then you have to put it in the magic box [a kiln]. You’re never quite sure what will come out. … With painting, you put a mark down and you know it’s there. With ceramics, there are always these horrible challenges. You never know.

Your work seems to have shifted. There is less whimsy and more political commentary.

I’m kind of a news junkie. It’s so crazy what is going on in this country. You can’t make this stuff up.

Sheila Farr, a regular UW Magazine contributor, described Warashina’s experience developing her artistic eye at the UW:

Warashina enrolled at UW and, as an elective, signed up for a beginning drawing class taught by graduate student instructor John Constantine (whose son Dow Constantine would go on to a prominent political career in King County). Instantly she was hooked. “I thought, wow, this is great; it’s amazing. I didn’t even know what a charcoal stick was. I found myself in there at night doing these drawings.” One quarter after another she signed up for drawing and then, in her sophomore year, tried a ceramics class. She never left. “I just wanted to spend my time there all the time. It was really sick. The tactile feeling of the material: it’s seducing.”

First she fell in love with the material and then later started to learn the history of ceramics and connect to the tradition of Japanese pottery. Respected UW ceramics instructor Robert Sperry, who had spent time studying in Japan, was influential in that evolution and, among other things, taught her about dealing with the surface of clay. “Bob told me to take a lot of painting, so I did … He was very influenced by Japanese brushwork and he taught me that.” The visceral, risk-taking work of ceramics instructor Harold Myers provided a counterpoint in Warashina’s training. She also took jewelry courses from Ruth Penington (1905-1998), a strong female role model and nationally known jewelry maker.

The UW art school was small in those days and Warashina was part of a particularly gifted group of students, including the painter Chuck Close (b. 1940). They’d all get together and party: students, grad students, and instructors. The artists wouldn’t leave their studio work until after midnight and even with those long nights Warashina wanted more. Before going home on Fridays, she’d leave a window open so she could sneak back in on the weekend:

“That’s how bad it was. I was really addicted. I had these roommates and they got mad. They said, ‘Patti, you need to go out at night.’ But I told them I like what I’m doing” (Farr interview).

She mastered the skill of “throwing” pots on a wheel, and even got into competitions with her male classmates to see who could pull 25 pounds of clay the quickest: shaping and controlling the material into a perfect vessel. She was good, but throwing didn’t hold her interest. She designed her pots to have surfaces she could draw and paint on. Her first exhibition as an undergraduate was at the Phoenix studio and gallery on Capitol Hill, owned and operated by the sculptor Philip Levine, where she also taught ceramics classes.

For more about the Spokane-born ceramics master, visit her artist page over at the Smithsonian. Below is an ad that the UWAA ran to honor Warashina in the Smithsonian catalogue.