Embracing the bay Embracing the bay Embracing the bay

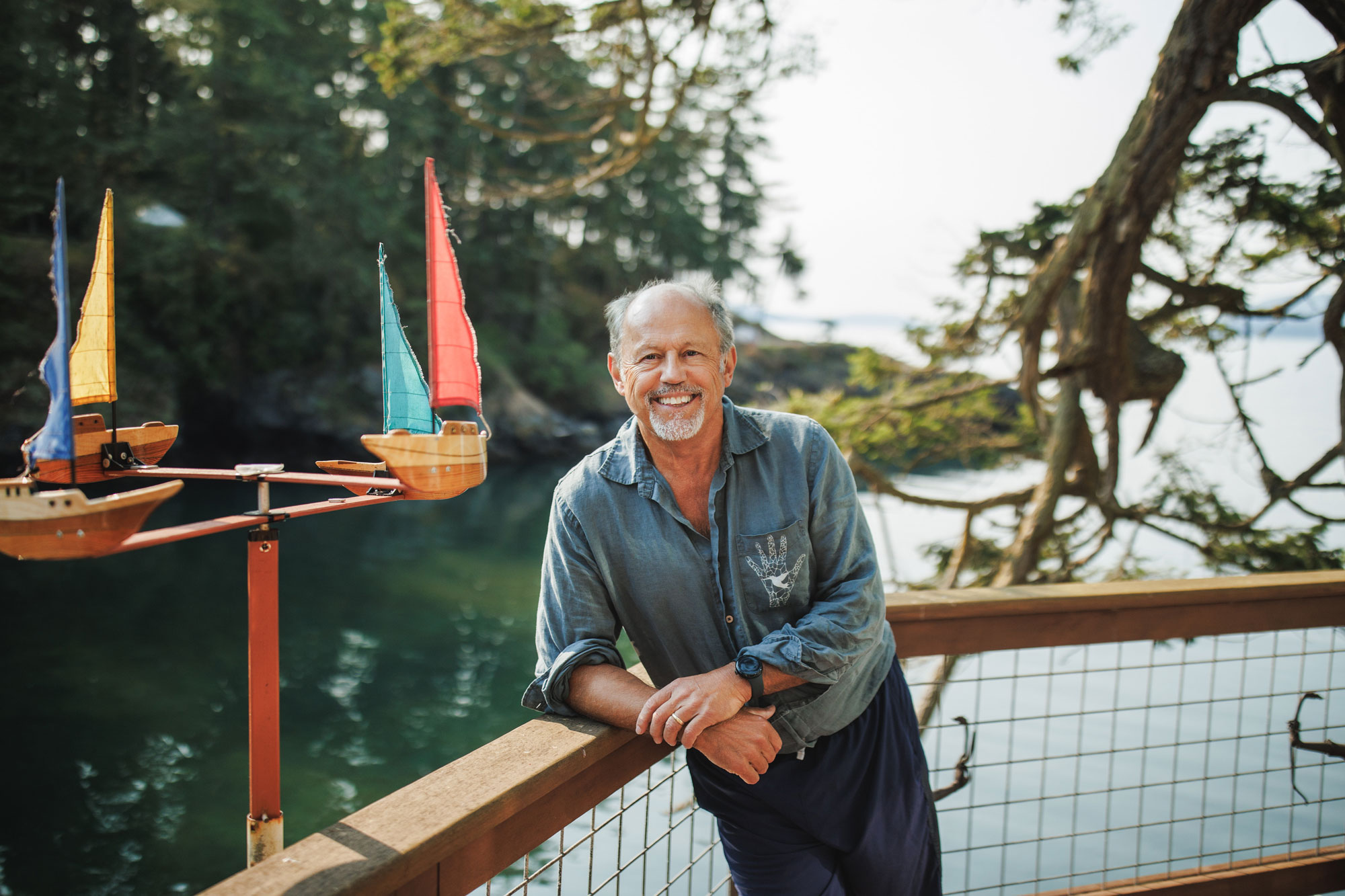

Joe Brotherton focuses on arts and well-being at Doe Bay, including a new festival with a “low-key Burning Man” vibe.

By Shin Yu Pai | Photo by Satya Curcio | September 2024

When Joe Brotherton, ’76, ’81, first discovered Doe Bay Resort with girlfriend Maureen Pleas, ’76, the pair were just teenagers. The 49-acre Orcas Island resort was a fabled place on the hippie trail. It boasted clothing-optional soaking tubs and incredible water views. The resort’s website notes that Doe Bay was once a place of tribal gathering and Native American potlatch.

Brotherton remembers revisiting the site years later, when he was thinking about purchasing the resort, and that his blood pressure dropped the minute he set foot there. In 2003, he bought the property to preserve its role as a cultural haven and to protect it from being broken into parcels and sold off.

As a Seattle-area entrepreneur, Brotherton acquired older apartment buildings and fixed them up. So the idea of taking on something in rough shape didn’t intimidate him. But unlike his other businesses, Brotherton looked at Doe Bay without worrying about profit. His other ventures and investments could allow Doe Bay to be a passion project centered on a “great experiment”—a place to practice radical hospitality and to pursue a higher ethical standard of business. “Did we treat the person or entity fairly? And do they perceive that they were treated fairly?” asks Brotherton. “We also judge ourselves by how we treat the least powerful.”

From the time he was 12, Brotherton played bass in a rock ’n’ roll cover band that gigged at parties all over Seattle. This early love for music fueled his passion for live music and led to the idea of hosting music events at the resort. From 2008 to 2019, Doe Bay Fest drew music lovers to discover new performers in a theater of nature.

The family friendly outdoor music festival, produced by Kevin Sur and Chad Clibborn, ’00, of Artist Home, hosted some of the region’s most beloved bands, including The Head and the Heart, Hey Marseilles, The Maldives, Shabazz Palaces and Naomi Wachira. Audiences stayed in yurts and cabins or camped. They could roam the forests, hike the trails and mingle with visiting artists.

Leaving the resort caused occasional “Doepression,” Brotherton jokes.

“There were no barriers,” says Brotherton. “You could hang out on the beach and listen to music. You’d be sitting on a log and look over and realize you were next to your favorite singer.” The creative proximity resulted in lots of connections and collaborations, including spontaneous late-night shows. Leaving the resort caused occasional “Doepression,” Brotherton jokes. “You went back to work but haven’t been able to do anything for three days because you’re still listening to The Long Winters at midnight.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Doe Bay Fest quietly ended, and Brotherton evolved the resort’s approach to the arts into a yearlong artist-in-residence program, providing songwriters a place to retreat and be creative. Now he’s preparing to host “Imagine,” a “low-key Burning Man meets Doe Bay,” he says. The new festival includes live music, yoga and meditation workshops, educational talks and art installations. Last year, the organizers created an “earth harp” on the beach by stretching piano strings across the cove. This year near a stream, Brotherton has installed a gilded Thai-made Buddha for visitors to interact with.

During college, Brotherton took a break to travel the world. He was awed by the expressions of Buddhism in Bhutan, Islam in Afghanistan and Shintoism in Japan.

He transferred to the UW from Fairhaven College, where he initially studied computer science and, as a 19-year-old, started a programming business. While excited by the innovations that technology brought, he felt the field moved too quickly. By contrast, the accounting end of business moved at an easier pace. “I was literally applying things within days of learning them to design someone’s cost-accounting system on their computer,” he says.

After college, he joined the PricewaterhouseCoopers accounting firm but came back to the UW after a few years to teach in the business school and study law. Brotherton excelled at contract and tax law and loved the complex problem-solving that lawyers get to do.

Today, Brotherton divides his attention across several nonprofit projects. He and his wife, Maureen, work with partners in Ethiopia and Uganda on community development projects like building wells and bee apiaries. He also works with prisoners at the Monroe Correctional Complex. The family also supports the Brotherton Scholars program at the UW’s law and business schools as well as Cornish College and Seattle University.