Speaker of the House Thomas Foley has led a distinguished career. Here’s a personal look at the UW’s alumnus of the year.

Each winter UW alumni, faculty and administrators meet to name that year’s Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus, the most “distinguished” alumnus of the University of Washington. Past recipients have included Nobel Prize winners George Hitchings and George Stigler, photographer Imogene Cunningham, newsman Chet Huntley and artist George Tsutakawa. This year the group turned to one of the most influential politicians the UW has ever produced, Speaker of the House of Representatives Thomas Foley. In a double honor, Foley will be this year’s commencement speaker at both morning and afternoon ceremonies held June 13.

With both his B.A. (1951) and law degree (1957) from the UW, Foley’s education has fostered a distinguished career in the House since 1964. His service to his district, his state and his nation represents his deep commitment to the ideals of American government. Columns asked Joel Connelly, the national correspondent for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and a 1971 UW graduate, to take a personal look at the man behind the headlines. What follows is his report.

* * *

The annual Down River Days parade in Ione, Wash., features antique cars, a mounted sheriff’s posse, and local officeholders gussied up in Old West outfits. House Speaker Tom Foley comes to Pend Oreille County clad in the same dark blue pinstripe suit that he wears in corridors of the U.S. Capitol.

“I have never been a suspender snapper,” Foley jokes when asked about his insistence on formal attire even when traveling to remote corners of his state.

Foley, 63, has never been seen as too big for his britches by citizens of Washington’s Fifth Congressional District. He is addressed as “Mr. Speaker” in Washington, D.C., but is called “Tom” in Ione. The britches are even smaller, since Foley lost 80 pounds in 1989-90 and has kept off the weight by pumping iron each morning.

But the imposing, reflective Foley finds himself under unprecedented pressure in the “other” Washington. While never sullied by scandal, some charge he has failed to straighten out the fractious House of Representatives over which he has presided since May of 1989.

The chattering classes of the U.S. Capitol were singing Foley’s praises three years ago when he appeared to restore bipartisan cooperation to the House. A new spirit of civility prevailed after the bull-headed rule of deposed Speaker Jim Wright.

Nowadays, however, some fault Foley for his slow handling of “Rubbergate,” the uproar over overdrawn accounts at the House bank.

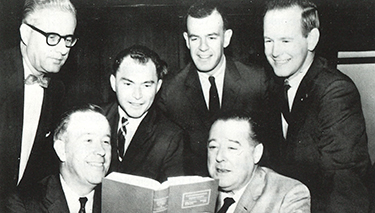

New Kid on the Block: Rep. Tom Foley joins the Washington state Democratic delegation in Congress after the 1964 LBJ landslide. Seated, left to right, are Sen. Henry Jackson and Sen. Warren Magnuson. Standing, left to right, are Rep. Floyd Hicks, Rep. Lloyd Meeds, Foley and Rep. Brock Adams. Photo from the Henry M. Jackson Papers, University Libraries.

Foley is smarting over what he feels is “inaccurate” reporting of the affair. In an April breakfast meeting with the press, he noted that all checks were covered and no checks bounced. “How does the public get the idea that checks were bounced?” he asked reporters. “Because that is what has been said and written.”

The Speaker also cited polls showing that about half the nation thinks taxpayers’ money was used to cover bad checks—when no tax dollars were involved. Most people think there were huge losses and that the bank is still operating, both untrue, he added.

What’s lost in the uproar is that Foley worked for years to pry open the secretive, seniority-bound House that he entered 27 years ago. He chaired the reformist Democratic Study Group when it proposed such then-radical reforms as election of committee chairs.

Foley is a cerebral, policy-centered man who operates with a close circle of advisors, largely Ph.D.s and former congressional fellows. He has never given much attention to administration, trusting office operations to Heather Foley, who serves as her husband’s unpaid administrative assistant.

Foley will defend his leadership style this fall as he campaigns for a 15th House term. If the Democrats suffer heavy losses in House races, Young Turks in his party’s caucus may revolt.

Foley is not likely to face a revolt at home. For 28 years he has been treated with respect and deference by his constituents, even Republicans. Once, during a tour of Pend Oreille County, a Republican county commissioner quickly approached Janet Gilpatrick, a Foley aide, to warn her that a reporter was asking pointed questions “about Tom.”

Foley was leaving a meeting with local business leaders in Walla Walla last year when a bit of craziness broke out. An early spring snowfall coated the parking lot. Aides, reporters and a few local merchants started throwing snowballs. But a cease-fire zone prevailed around the House Speaker’s 6-foot-3-inch frame. One participant said later that aiming a snowball at Foley would have been akin to beaning the Pope.

“Tom is a gentleman. That is one aspect of the man that will never change,” says Scott Lukins, a Spokane attorney and longtime friend.

Foley is renowned for using quips to deflect questions about what makes him tick. Occasionally, however, he opens up. The Speaker speaks movingly of his childhood introduction to social justice, when his parents took him to see neighborhoods in Spokane where the Depression-era unemployed lived in shacks and lean-tos.

Probably the greatest influence on Foley was his father Ralph, a longtime Spokane Superior Court judge. After over a quarter-century in Congress, the speaker is still occasionally referred to as “young Foley” by older constituents.

* * *

Foley has brought a judicial temperament to the legislative process. He is cautious to a fault on major decisions, insisting that all arguments be heard and every party be allowed to speak. Symbolically, Foley's inner office is not dominated by an imposing desk behind which orders are given. Instead, it has couches for discussion and relaxing tension.

When Foley does take a bold stand, it reflects a devotion to the law. He was out front in opposing President Bush’s efforts to put an anti-flag burning amendment in the U.S. Constitution. And nobody who witnessed it will ever forget an exchange with Rep. Norm Dicks over an anti-busing measure. The two lawmakers were at a Capitol Hill restaurant, when Dicks started wringing his hands over how to vote on the popular but constitutionally questionable bill. “Norm, you’re a lawyer,” thundered Foley, grabbing his colleague’s lapels. “This is bad law. Norm, you are going to vote AGAINST this!” Dicks did as he was told.

Foley has a trial lawyer’s skill at closing arguments. Over the years, he has often been picked by Democratic colleagues to conclude debate on important issues. The speaker can thunder and command attention, bolstering his case with arguments taken from copious historical reading.

An undoubted high point of Foley’s speakership was last year’s House debate on the use of military force in the Persian Gulf. “There are constitutional responsibilities that we owe to our constituents and our country,” Foley told colleagues. “We are required to speak on the issue.”

By custom, the Speaker does not participate in House votes. But Foley insisted that he be recorded on what he called “this momentous decision.” He voted in favor of continued sanctions and opposed going to war.

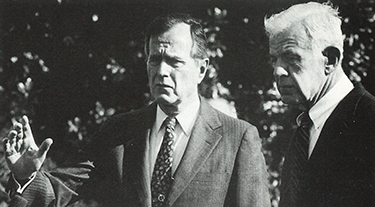

Time of Trouble: President George Bush and House Speaker Tom Foley speak to reporters Jan. 22, 1991, shortly after captured American pilots are paraded before Iraqi 1V cameras during the early days of the Gulf War. As House Speaker and second in line to the presidency, Foley is consulted on all major domestic and international crises. Photo by Barry Thumma. Wide World Photos.

House floor oratory makes fine theater, but Foley spends most of his time working backstage at the politics of conciliation. It has been his trademark since the 1964 Lyndon Johnson landslide swept the young lawyer into Congress.

Foley was initially encouraged to run for Congress by Sen. Henry M. Jackson, for whom he had worked on the Senate Interior Committee. Typically cautious, Foley planned to wait until 1966 before taking on longtime Republican incumbent Walt Horan. At a meeting in the Spokane Club, friends goaded him into a last-minute decision to run. Foley reached Olympia minutes before the filing deadline after blowing a tire en route.

In his first term, Foley displayed the same skills that made ‘Scoop’ Jackson a power on Capitol Hill for 40 years. He was able to master details of legislation, was skilled at the art of legislative compromise, and put a politician’s high value on loyalty. Starting with Hubert Humphrey in 1968, Foley has stood beside a succession of losing Democratic presidential candidates on visits to his Republican-leaning district.

Foley is far different from Jackson in one respect. He has a fine, self-deprecating sense of humor. Foley is the butt of most stories he tells. He recalls hanging on for dear life as his horse galloped past laughing spectators at the Omak Stampede.

One reason for Foley’s mellow demeanor is that he was never forced to fight like a wolverine. Power has sought him out. An initial break came when “Watergate babies” elected in 1974 used new rules to depose elderly committee chairmen. House Agriculture Committee Chairman W.R. Poage was their first target. Foley defended Poage, offering to speak for him in caucus. When the elderly Texan was voted out, however, Foley was voted his successor.

The Reagan landslide propelled Foley into the House leadership. A pair of Congress’ grandees—House Majority Whip John Brademas and House Ways and Means Chairman Al Ullman—had lost their seats. Illinois Rep. Dan Rostenkowski was given his choice of the two jobs. He picked ways and means. Foley was unanimously elected majority whip, third-ranking position in the Democratic leadership.

Foley had no opposition when he ran for House Majority Leader in 1987. He inherited the Speakership two years later, after defending Jim Wright against allegations of financial impropriety that eventually sent Wright packing back to Texas.

Foley has operated on one central premise the last 12 years. He feels the American people knew what they were doing in electing Republican presidents while giving Democrats control of Congress. The White House’s task was to set the country’s direction, while Democrats on Capitol Hill had the job of providing for the people’s needs. In Foley’s view, the two ends of Pennsylvania Avenue have the duty to work together.

The approach often worked. A Foley-led Democratic majority successfully compromised with the White House to rewrite and strengthen the Clean Air Act. A 1990 budget compromise, while unpopular, will cut anticipated federal deficits by $450 billion over five years. Earlier, during budget impasses in the Reagan years, Foley’s office was a preferred bargaining site for administration officials and congressional leaders.

While immune from snowball fights back home, Foley’s centrist position has made him a target of bomb throwers at both ends of Capitol Hill’s ideological spectrum. Liberal Democrats are seething at Foley for not being partisan enough. They feel he lets Republicans play a double game of posing as enemies of big spending while quadrupling the national debt.

The attack from the right has come from House Republican Whip Newt Gingrich. Gingrich has devoted himself to wresting control of the House from the Democrats, at whatever cost. He instigated ethics charges against Wright. And he has directed low blows at Foley, including letting an aide spread personal smears against Foley. The rumor blew up in Gingrich’s face. He apologized to Foley, but has resumed personal attacks lately.

Some observers say that Foley rarely goes out on any limbs. He has sided with the National Rifle Association on most key gun control decisions, including the Brady bill. He disappointed conservationists by excluding the Kettle Range from Washington’s 1984 wilderness act, and was slow to recognize health hazards caused by nuclear weapons production at Hanford.

Yet Foley has displayed a steely self-discipline that has helped carry him through many crises. He quit a two-pack-a-day cigarette habit cold turkey, and rarely drinks. The Speaker follows a daily workout regime even when he is traveling.

* * *

Foley is not a pork barreler in the tradition of Jim Wright or Tip O'Neill. "He does not go out and aggressively seek things for us, but some things come here because he is the leader," says Joel Crosby, a Spokane city councilman. But the Speaker is careful to protect federal plums in eastern Washington, from the B-52 bombers at Fairchild Air Force Base to the Army Corps of Engineers Walla Walla office.

He usually makes it home to eastern Washington an average of twice each month. The Speaker can look like a rumpled salesman on a Friday night at Washington, D.C.’s National Airport. On more than one occasion, he has rushed to a phone booth to change plans when Northwest’s evening flight to Seattle takes off too late for him to catch the last connection to Spokane.

Sooner or later, most congressmen exchange the grind for riches and a more relaxed life. Not Foley. When elected speaker in 1989, he told the House that serving in it was “the great and abiding pride of my life.”

“I believe that public service is a free gift of a free people and a challenge for all of us in public service to do what we can to make that service useful for those who have sent us here,” he said.

“We are proud to call this the People’s House, the fundamental institution of American democracy.”

During his years as a University of Washington undergraduate, graduate student and law student, Tom Foley developed intellectual habits and personal tastes that have not varied over nearly 40 years.

During his years as a University of Washington undergraduate, graduate student and law student, Tom Foley developed intellectual habits and personal tastes that have not varied over nearly 40 years.

Foley was active as a Young Democrat, loved to debate politics, and devoured history with particular attention to England. He was interested in modern furniture, and irresistibly attracted to electronic gadgets and audio equipment.

“He developed then, and he’s continued since, an interest in conservative clothing. He would purchase a suit at Albert Ltd.,” jokes Scott Lukins, ’54, a Spokane attorney who shared a house in Greenwood with Foley.

Memories of Foley in the 1950s fit perfectly with the House Speaker of the 1990s. A visitor last year was sent to wait for Foley in his inner sanctum. A. Bach cantata boomed out of the Speaker’s stereo speakers. A shelf in the corner was piled high with history books set aside for Foley’s upcoming vacation.

Back in the ’50s, recalls Lukins, Foley “never watched television for sporting events …. He did not have a great deal of interest in sports, period.” Four decades later, as the Speaker took part in a bid to save the Seattle Mariners, Heather Foley confided to a friend that her husband leaves the room whenever she turns the TV channel to a baseball game.

Foley describes his years at the UW as “an interesting, challenging period.” He jokes about being under perpetual deadline pressure to finish papers—and enlisting dates for typing duty.

Foley completed his undergraduate studies in 1951, after transferring from Spokane’s Gonzaga University. He delayed law school to take graduate courses in history.

The intellectual pursuits of the 1950s, particularly his interest in history and diplomacy, have aided Foley’s subsequent career. He arrived at the Speaker’s podium with an encyclopedic knowledge of parliamentary history and with a wealth of funny anecdotes about Britain’s House of Commons. Dick Larsen, a former aide and later associate editor of the Seattle Times, recalls that “a high point” in Foley’s career was his invitation to speak at the Oxford Union.

Between his B.A. and law school, Foley took Russian studies at the UW. Thirty-five years later, he dined three times with Mikhail Gorbachev during the Soviet leader’s 1987 visit to Washington D.C. He had led a House delegation to meet with Gorbachev earlier that year.

Looking back at Foley’s college days, no one would ever describe him as a hellraiser. “He didn’t date a lot,” recalls roommate Lukins. The future Speaker kept busy working with young offenders in the King County Juvenile Court instead.

Foley did acquire habits at the UW that he would. later break. He was addicted to junk food before it was known as junk food. Once he became Speaker, he shed 80 pounds of flab. “The efforts to get himself in condition began in Congress,” notes Lukins.