For 35 years the University of Washington has honored the exemplars of its first mission — teaching. More than 175 faculty have been given a UW Distinguished Teaching Award since 1970, and this year seven more from Seattle, Bothell and Tacoma join their ranks. In addition, the UW salutes 12 other professors, graduate students and staff members for their public service and teaching excellence. What follows are brief profiles of the seven teaching award winners, and then a listing of the other winners.

Distinguished Teaching Award

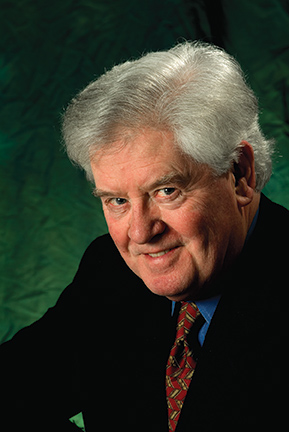

Michael Allen

Michael Allen

Professor, UW Tacoma

Professor Mike Allen has a secret identity.

The problem is, it’s not really a secret. Nearly everyone at UW Tacoma knows that Allen-a seemingly mild-mannered history professor in the interdisciplinary arts and sciences program-occasionally dons a blue sequined vest and black top hat to become Mike the Magician, purveyor of tricks that mystify and delight.

His act is popular at UWT events, where he twists long balloons into animals and pulls dollar coins from the ears of students. During magic shows, his energy brings a smile to everyone who watches-and in the classroom, that same energy sparks a hunger for history among his students.

It’s a teaching style that Allen calls “lively.” His students call it refreshing.

“Even though he has taught this subject time and time again, his enthusiasm for it is infectious, like a good storyteller who cannot wait to get to the really good parts of the tale,” says Mark Dodson, a graduate student at UWT who took Allen’s American history course. “His style of teaching made me fall in love with history again.”

Allen, a native of Ellensburg, discovered early in life that he loved history. Disney movies from the 1950s-such as Davy Crockett-piqued his interest in the Old West and the American Revolution. Teaching history, he says, is really just a matter of telling stories.

“It’s really an honor to be able to get up and tell stories for a living,” he says. “All I do is tell stories. They all have a theme or a thesis, but they’re stories.”

Allen has a fascinating history himself, with experience ranging from fighting in Vietnam to working on Mississippi tugboats. A fan of the Ellensburg Rodeo, he founded the Ellensburg Rodeo Hall of Fame Association and hopes to establish a rodeo museum in Ellensburg. He wrote about rodeos in a recent book, Rodeo Cowboys in the North American Imagination, and has also authored books about Western history. His first book, Western Rivermen, 1763-1861: Ohio and Mississippi Boatmen and the Myth of the Alligator Horse, drew on his experience on the Mississippi River.

In 2004, he published the acclaimed A Patriot’s History of the United States: From Columbus’ Great Discovery to the War on Terror with co-author Larry Schweikart. He is currently working on books about the Confederation Congress and the Ellensburg Rodeo.

His other hobby, magic, takes him to children’s shows, UWT events and other venues. He juggles, tumbles and performs simple tricks that are very popular with children-when they work. “I’m not a real great magician,” he says. “I’m a comedy magician. My tricks aren’t that good.”

Allen says he, like other children, became interested in magic around age 9. He pursued it until he had mastered some tricks.

“Most kids go through a little magic phase, but I stuck with it,” he says. “Actually, I wanted to be a magician before I decided to become a professor.” — Jill Carnell Danseco

Carole Kubota

Carole Kubota

Professor, UW Bothell

The worst teacher she’s ever known made a big impact on Carole Kubota, ’68, ’77, ’85. Her junior high teacher taught her a lesson she never forgot-that science had to be learned by rote, that it was dull and very black and white.

Fortunately for 37 years of UW science education students, the next person to have a big effect showed her just the opposite.

As a UW undergraduate in the ’60s, Kubota wanted to become a teacher-but not a science teacher. She majored in sociology. But everything changed in her senior year when she took a class from Botany Professor Arthur Kruckeberg.

“The first day of class he said science isn’t a bunch of stuff to memorize. It’s a way of looking at the world and making observations and generalizations from those observations,” Kubota says. “Once I heard that, I switched majors.” Graduating with a degree in biology with such a late start was no easy feat, but Kubota had seen the light. Her grad-school adviser, Education Professor Roger Olstad, also focused her ambitions. The two UW professors became her role models.

After earning her bachelor’s degree, Kubota joined the fledgling Pacific Science Center as an instructor and learned a thing or two about having fun with science. “We had to make the classes interactive and exciting,” she relates. Teaching kids and their teachers during a seven-year stint at the center while simultaneously working on her UW graduate degrees, Kubota developed her teaching style. “You have to grab people and make learning interesting,” she says.

She does this by making learning interactive, by using simulation games to get a point across, by facilitating lively group discussions, by taking field trips, by never answering questions except with more questions, and by any means that works. You won’t find her lecturing at the front of the room. In fact, you’d have a hard time picking her out if you visited one of her classes. She might be listening to a group discussion, helping locate materials for a project or prodding students to dig deeper into their understanding of what it means to be a teacher.

She enjoys the challenge of turning science-anxious pre-service teachers into science advocates through classes that keep everyone engaged. “I believe the students in my classes are rarely bored,” Kubota says. “They are challenged to think, rather than memorize.”

Students appreciate her methods as well as her madness. “When Dr. Kubota entered the classroom she brought with her an energy that was infectious,” writes a former student in support of Kubota’s teaching.

Teachers teach the way they were taught, Kubota notes. She shows teachers-in-training how to make science exciting in their own classrooms. A perfect example presented itself when a former student brought his fifth-grade class to the Bothell campus. Kubota’s pre-service teachers helped the class conduct pillbug races as the culmination of a science lesson.

One of the concepts she wants her students-and their students-to get is that real scientists don’t find the answers in the back of the book. Instead, science is a continual quest for answers that only lead to more questions. “You never get to the end,” she says.

Kubota is in this for the thrills. “When I come out of a class that has really gone well, I’m energized, because to see the students learning-from each other and themselves as much as from me-is so exciting. Helping them to grow and expand on their own thinking is very satisfying. It’s just joyful.” — Beth Luce

Laura Little

Laura Little

Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychology

In every right-brained field of study there is a left-brained course that nobody wants to take-statistics. The word sends shivers down the spines of undergraduates. So when Laura Little tells people she teaches statistics, it’s a conversation stopper.

But she sees statistics as more than numbers and technical recipes. Little sees the underpinnings of what psychologists do. “We try to measure things that are difficult to measure, like intelligence, arousal, inhibition,” she notes. How do we know that we really understand human behavior? How do we prove theories that can be used to help people? The answer lies in statistics.

Trained as a behavioral scientist, Little is also an attorney. She practiced criminal law for seven years before deciding she was more interested in looking at the admissibility of scientific evidence and how it becomes acceptable in the science community. She went back to school and earned a doctorate in psychology with an emphasis on quantitative methodology.

There are close similarities between using evidence to prove a case in court and using statistics to prove your theories in psychology, Little says. “How do we support the claims we wish to make, and by what standards should we deem such claims persuasive?”

When given the opportunity to teach students about methodology and statistics, she knew she had found her niche. Even as a graduate teaching assistant, she began accumulating awards for teaching the courses nobody wanted to take. Today she has a reputation for making statistics come alive and for having a steady stream of students passing through her office for advice on how to cope with the mountains of data they collect in their own research projects.

Little knows that mathematics and statistics are difficult for most students, especially those more interested in content classes such as cognitive psychology, human memory and aggression. But students often aren’t aware of how quantitatively driven psychological research is. She remembers herself as an undergraduate, just wanting to be a sponge and absorb everything.

“That’s fine for a while, but at some point you want students to start asking questions and challenging and pushing a little bit,” she says. “I’m trying to train them to be scientists, not just people who know a lot of things about behavior. It’s very difficult to be a psychological scientist and not be well trained. I treat all my students as if that’s what they want to be.”

A graduate student describes Little this way: “Even though she knows the material very well herself, she knows where concepts become difficult for beginners, and she can tailor her explanations to this level. . She uses gray areas of statistics to spark the intellectual curiosity of the strong students without overwhelming the students who are not ready to deal with such thoughts.”

With a combination of a sincere invitation and a good sell, Little means to convince students of the value of statistics. And it usually works. The same grad student writes, “Every quarter some students end up discovering that they think statistics is pretty cool.”

Another writes, “In teaching a subject reputed to be colorless, tedious and technical, Dr. Little’s sense of intellectual excitement and educational mission is infectious. The classroom environment in her statistics courses is bright, engaged and focused.”

Statistics stretches students’ abilities, Little knows. “It’s good mental exercise. They may be sore, but they’ll feel like they’ve achieved something.” — Beth Luce

Mehran Mesbahi

Mehran Mesbahi

Professor, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Students in Mehran Mesbahi’s Orbital and Spaceflight Mechanics course study Johannes Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion, explaining how planets and comets orbit around the sun. They also learn the human part of the story: how Kepler came up with the laws, how many tries it took before he got it right and how radical his ideas seemed at the time.

Kepler wrote poetry, which Mesbahi reads in class. “He was deeply involved in attempts to understand nature. He was looking for a universal beauty in nature. I think many people connect with that desire. When I attach the theorems to this desire, students remember it,” Mesbahi says. “I truly believe there is beauty in the technical aspects.” He wants students to remember the driving force behind the science, “the human desire to understand nature and its beauty.”

Mesbahi teaches students about the early scientists who formulated the basis of their profession: Copernicus, Galileo, Brahe, Kepler and Newton. “The lives of the scientific giants provide an opportunity for exposing the students to how science is actually done,” writes one of Mesbahi’s colleagues, “not as a glorious, smooth path to a discovery, but often through unusual self-determination, controversies and rivalries.”

Mesbahi introduces the historical, cultural and political background behind science through the use of poetry, literature, movies and newspaper articles. He talks about the long-held desire of humans to travel to other planets. “From our childhood there was always this unknown universe outside the earth-the stars and interplanetary travel,” explains Mesbahi.

Studying Kepler, who left detailed accounts of the many errors he made before arriving at the correct natural laws of planetary motion, offers a chance to show students that making mistakes is part of the process of discovery. “Students should be involved in seeing that engineering is not done in one shot,” Mesbahi says. “What you see as the final structure was destroyed many times before you get the final product.”

In the classroom, Mesbahi draws on his experience working at Cal-Tech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) on projects such as the Cassini mission to Saturn. Although he’s conducting five research projects funded by JPL, Boeing and the National Science Foundation (NSF), Mesbahi is just as committed to teaching. He has gathered many awards for teaching and research, including an award as a teaching assistant at the University of Southern California, an NSF Career Award and last year being voted professor of the year by students in his department.

Mesbahi teaches in a classical style, lecturing in front of the class and using a blackboard, overhead transparencies and PowerPoint presentations, reports his department chair. “But he does so in a way that establishes a unique one-to-one bond between him and each student in the classroom. It is a remarkable phenomenon. . Each of his students, no matter whether the class is comprised of 60 undergraduates or 10 graduate students, regards Mehran as his or her own ‘personal professor’ and trusted mentor.”

Mesbahi’s students appreciate the care with which he challenges them. One student comments, “I have never had a course where the difficulty enhanced the desire for knowledge.” Another writes, “This class was very, very interesting. It stretched my mind beyond repair.” —Beth Luce

Philip Reid

Philip Reid

Professor, Department of Chemistry

In the annals of university teaching greatness, the highest accolades often go to those who teach subjects in arts and letters. But science teachers have a harder row to hoe. Phil Reid is one of those unusual teachers who can make a difficult subject-chemistry in particular-memorable and fun. As one appreciative student puts it, Reid’s talent is “creatively teaching material whose defining characteristic is a lack of room for creativity.”

It’s difficult to jazz up an introductory science course, Reid notes. But he finds chemistry and science “super interesting,” and hopes his enthusiasm rubs off on students. Apparently, it does. Last year he received the department’s teacher of the year award-not the first time Reid has been recognized as an effective teacher. He received several graduate teaching awards while doing doctoral work at Cal-Berkeley. Since joining the faculty at the UW, he has won a Career Award from the National Science Foundation and a Cottrell Scholar Fellowship from the Research Corporation. The two national awards recognize beginning faculty members who excel at both research and teaching.

Reid has a knack for explaining difficult concepts, which he does for students ranging from 450 freshmen in the introductory chemistry class to a handful of graduate seminar students. “One of Professor Reid’s most impressive skills is his ability to clearly articulate even the most difficult concepts,” writes a former honors student.

What he likes most is when his students challenge him. “Science continues to evolve and learn new things. And the way you learn new things is by questioning the old,” he says. “I really love it when they challenge something I put forth in class. Those are the moments you look for, the ones that allow you to teach at a deeper level.”

Reid has had an impact on his department. He has redesigned courses to bring them up to date with current teaching methods and been a leader in using the Internet to augment classes. He and other faculty members have revitalized a robotics colloquium, bringing national speakers to large campus audiences.

Remembering that he got hooked on research as an undergraduate at the University of Puget Sound, Reid invites promising undergraduates as well as graduates to join his research team. “That’s one thing UW has to offer that a lot of other institutions don’t,” Reid says. “There’s a richness of diversity in research going on here.”

A graduate student who worked on Reid’s research team writes, “Phil revealed to me the joys of science, while at the same time providing a candid analysis of good and bad scientific ethics and revealing the contrast between medium- and high-quality technical work. He helped me see truths about the politics of science and academics without souring my outlook.”

Lessons learned in the lab are important, Reid says. “It’s a whole different skill set: How do you define a problem? How do you design experiments that will tell you what you want to know? The struggle of research-it’s not like you come in and flip three switches and boom, there’s the answer. You have to wrestle this stuff to the ground. That’s something you really don’t see in the classroom.”

Reid believes that the University offers students a message of possibilities. “I really respond at a deep level to the students coming here with hopes and expectations,” he says. “You have a responsibility to meet those hopes and expectations with every skill you can bring to bear to help them along on that journey.” — Beth Luce

Julie Stein

Julie Stein

Professor, Department of Anthropology

As a girl, Julie Stein used to dig in an empty lot and pretend to make important discoveries. In college, she discovered geology. “I thought explaining why you found the buried thing was even more fun than finding it. The more difficult the explanation, the better.”

Now she’s a professor and geo-archaeologist specializing in shell middens (prehistoric garbage heaps) who introduces students to the joys of getting dirty. Her fondness for archaeology has not dimmed since childhood, and she shares it with everyone she can.

It takes a certain type of person to enjoy shell middens. “You have to like the challenge of taking a complicated thing apart,” Stein says, adding that she doesn’t much care about the pyramids (they stick out of the ground) or classical Greek archaeology (too weird). But she’s crazy about using the surrounding soil itself to help answer questions about artifacts and try to figure out how the objects ended up there. Not many scientists approach archaeology in this way, and students come from all over the country to take her classes.

“While Julie has proven herself to be a great researcher, her commitment to training archaeology students in geo-archaeology is her greatest strength,” writes one of her former students, now a geo-archaeologist at the University of Illinois, Chicago. “She gets students involved in actual geo-archaeological projects.”

Students work with real artifacts in Stein’s classes. As a curator at the Burke Museum, she uses the collections to introduce students to the thrill of archaeology. They examine pieces, identify the artifacts and find out everything they can about them-how old they are, what they’re made of, where they came from, what they were used for-just as professional archaeologists do. “Everybody likes to discover things,” Stein explains. “If you let them discover it, they remember it.”

Stein has done research on various shell middens in the Northwest, primarily in San Juan Island National Historical Park, where historic military encampments were built on top of Native American sites at least 2,000 years old. She ran a field school there with undergraduate students from 1984 to 1991, excavating the site and cataloging their findings.

Hundreds of visitors to the park would come by to watch, and Stein thought it was a shame they couldn’t be included. So when King County asked her to excavate a shell midden on Vashon Island in 1996 she agreed, on the condition that the public be allowed to help. Working with amateurs “was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done,” she says, “but also one of the most successful.”

In a four-hour session, volunteers would dig a small bucketful of the shell midden, screen it, separate shell and bone fragments from sand, and participate in a whole range of archaeological activities. In the process, they’d ask questions about why they were doing this and what could be learned from it. “That’s where the real education took place. It was wonderful to realize that if you get people to do archaeology, they appreciate and learn so much more about it.”

A few years ago Stein and some students set out to locate the site of Lewis and Clark’s winter 1805 encampment in Oregon by looking for the one thing that would have had the most lasting effect-the privy. Soil samples from the spot should include mercury, used to cure syphilis among the crew, as well as high levels of phosphorous from the excrement. Stein hasn’t found the spot yet, but hasn’t given up. It’s just the sort of complicated puzzle that she and her students enjoy mucking about in. — Beth Luce

Louis Wolcher

Louis Wolcher

Professor, School of Law

Lou Wolcher is famous for his stick figures – drawings and diagrams he uses in his classes, made up of simple shapes and imaginative representations. His Malpractice Mountain drawing, showing the various standards of care for medical malpractice suits, and the Pizza of Federal Jurisdiction, explaining areas of federal court authority, become vivid templates that help students understand difficult concepts. “I just found over the years that it’s very efficient,” Wolcher explains, “and most students appreciate having that kind of visual representation.”

Wolcher has an innate ability to explain complicated concepts. According to one former student, he brings “arcane legal concepts to life with humor, poignancy, movie references, and a splash of colorful language.”

That includes his famous Wolcherisms. Although he doesn’t consciously do it, he often invents phrases that so precisely apply to a concept that the whole school picks them up. “Kill the puppy” is when a case goes to summary judgment and is not allowed to grow into a mature trial. “Poofify” refers to the negation of consent by certain factors, such as fraud or mistakes. And when he can only briefly mention a vast subject in class, he’s giving “a photocopy of a picture of a wax replica of an hors d’oeuvre” of the topic.

These idiosyncratic teaching methods lay the groundwork for understanding legal concepts so the class can move on to the part that Wolcher really likes-thinking. “My main concern,” Wolcher says, “is to get people to think.”

Current events, such as tort reform and the Terry Schiavo case, often serve as jumping-off points to help students discuss the broader implications of legal theories. “What’s really interesting is not how complicated the concepts are, but the social and moral questions that they attempt to resolve,” he says.

One undergraduate student in an honors philosophy class writes that Wolcher “forced us to reconsider our thoughts at the most basic level. Just thinking about the questions Professor Wolcher might pose in response to my paper forced me to question even further.” She adds, “Professor Wolcher encouraged the class to face controversial ethical and moral dilemmas, asking us to dissect and piece back together human nature. No subject was off limits, and he urged the entire class to examine issues from all sides.”

Teaching, research, reading, writing and deeply contemplating what he’s learned are Wolcher’s favorite activities. He instills this passion for academics into his classroom work. “My love has always been philosophy and legal theory,” he says. “That is always present, whatever I’m teaching. It’s one of the things that is a constant anchor for all my endeavors.”

He believes that law school should teach more than the skills of good, competent lawyering. Students, he believes, should take advantage of their last opportunity to really think about things before they have the pressure of jobs, clients and billable hours. “It’s one of the great privileges and great gifts of Western civilization to have this university structure where we do more than just train people to be cogs in the machine,” he says. “We train them to be thinking people and citizens.” — Beth Luce

Excellence in Teaching Award

Mae Henderson

Mae Henderson

Department: Women Studies

Courses Taught: Race, Class and Gender; African American and Native American Women; History of Afro-American Women and the Feminist Movement

Achievements: Henderson, a doctoral candidate in women studies, is the first in her family to attend college. As a single parent, Henderson is known for her drive and dedication in her teaching. She challenges herself and her students with open discussion of discrimination and racial stereotypes, despite possible obstacles and resistance that may keep others from teaching the same material. Absorbing the energy of their teacher, students say they leave her courses with a questioning, open mind and an empowered voice to support the rights of less privileged persons.

Quote: “[This class] really became a source of light for all of us. I am anxious to start my life after college and I’m so blessed to have ended it with this experience. I have so much to take with me and so much to give back.” —Josie Gomez, ’03

Degrees: B.A., California State University, Long Beach, 2000

Jennifer Lavy

Jennifer Lavy

Department: School of Drama

Courses Taught: Introduction to Drama, Play Analysis

Achievements: Lavy, a doctoral candidate in theater history and criticism, continually experiments with new ways to engage her students. Her philosophy emphasizes creating a classroom where students develop their own ideas and interests rather than focusing on what the teacher wants. She is one of the first School of Drama instructors to teach academic classes with new technology, such as the Web and online discussion boards. This year she is leading all post-show discussion sessions for the school’s main stage productions. She is also the founder and co-artistic director of the Akropolis Performance Lab, an experimental company working in the tradition of Polish stage director and theatrical theorist Jerzy Grotowski. Prior to entering the UW’s Ph.D. program, Lavy was the School of Drama’s director of development and a managing director at Seattle’s Freehold Studio/Theatre Lab.

Quote: “She has a depth of knowledge of her field so deep that she may draw parallels between The Simpsons and Ibsen’s A Doll’s House that both clarify the work at hand and enhance student interest. In addition to the breadth and depth of knowledge and the interest she brings . is her ability to draw great new things out of her students.” —student Markus McVay

Degrees: B.A., University of Akron, 1991; M.A., University of Akron, 1996

Marsha L. Landolt Distinguished Graduate Mentor Award

Recognizes an Outstanding Faculty Member Who Advises Graduate Students

Lesley Olswang

Lesley Olswang

Department: Speech and Hearing Sciences, 27 years at UW

Courses Taught: Social and Cultural Aspects of Communication; Clinical Methodology for Documenting Change in Communication Disorders; Clinical Research in Communication Disorders

Achievements: Olswang’s current research focuses on two areas: development of early signals of communication in infants, and social communication deficits exhibited by school-age children. She is a Fulbright Scholar, an Asha Fellow and an affiliate of the Center on Human Development and Disability and the Virginia Merrill Bloedel Hearing Center. She won a UW Distinguished Teaching Award in 1983. Students and colleagues alike most often hail her for her ability to balance her work and personal life while mentoring graduate students.

Quote: “Lesley provided a role model of a woman who could achieve excellence in academia and at the same time prioritize mentorship and teaching. … She required excellence on my part, encouraging me to improve my research and writing and critical thinking skills. She both challenged and led by example, as she demanded the same high quality work of herself.” —student Heather Carmichael Olson, Ph.D.

Degrees: B.S., Northwestern University, 1969; M.A., University of Illinois, 1971; Ph.D., University of Washington, 1978

Sterling Munro Public Service Faculty Award

Recognizes a Faculty Member Who Encourages Community-Based Instruction

David Olson

David Olson

Department: Political Science, 31 years at UW

Courses Taught: City Politics, State Government, Politics of Urban Reform

Achievements: Olson’s experience researching and teaching in state and local government, city politics and public institutions, including the Port of Seattle and Metro, has helped him sponsor hundreds of individual student internships. Olson is credited with being the main force behind the success of the political science department’s full-time Olympia internship program in which 15 to 20 top students work in the Washington State Legislature. Though officially retired this month, he will remain involved with the Olympia internship program and will serve as professor emeritus of labor studies at the Harry Bridges Labor Center, which he helped develop.

Quote: “Professor Olson has exemplified leadership in service learning, public service internships and community partnership projects through his teaching, the system and approach to service learning that he instituted, and the results of his dedication: generations of students who have gone on to become community leaders like me who are now bringing up the next generation of active citizens and social-change agents.” — former student Bea Kelleigh, director, Early Care and Education Coalition; and partner, Cedar River Group

Degrees: B.A., Concordia College, 1963; M.A., University of Wisconsin, 1966; Ph.D., University of Wisconsin, 1971

Outstanding Public Service Award

Recognizes a Faculty or Staff Member Rendering Exceptional Public Service

Bruce Psaty

Bruce Psaty

Department: Medicine, Epidemiology, and Health Services, 19 years at UW

Achievements: Last November, he told the U.S. Senate Finance Committee the painkiller Vioxx was linked to heart attacks and strokes. Despite criticism from the drug industry and government, Psaty has continued to expose the flawed studies of drug companies that gained FDA approval for this and other pharmaceuticals for over a decade. Alerting the public to the hidden risks associated with major prescription drugs, Psaty’s research has saved lives. In his spare time, Psaty has volunteered for 57 national and international medical committees, served on panels and editorial boards for more than 20 medical journals, and worked as a consultant on drug safety for Senate committees on finance and health. He recently helped Sen. Charles Grassle (R-Iowa) draft a bill making drug studies open to public review. Psaty does not accept funding from drug companies for his research, getting almost all his funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Quote: “He has conducted robust research and taken forceful and courageous stands that have protected hundreds of thousands of patients from unnecessary injury or death from dangerous drugs.” — Medicine and Health Services Professor Stephan D. Fihn

Degrees: A.B., Princeton University, 1972; M.A., Indiana University, 1975; Ph.D., Indiana University, 1979; M.D., Indiana University, 1981; M.P.H., University of Washington, 1986

Distinguished Contributions to Lifelong Learning Award

Recognizes a Faculty Member Rendering Exceptional Service to Continuing Education

Maria Gillman

Maria Gillman

Department: Romance Languages, 15 years at UW

Courses Taught: Literatures of the Maya World, Introduction to Hispanic Cultural Studies

Achievements: Students may have difficulty keeping their heads in their textbooks if Gillman is their professor. Teaching at UW’s Intensive Summer Institute for Spanish Teachers since 1998, she serves as on-site co-director in Oaxaca, Mexico, and Antigua, Guatemala. Gillman, who coordinates the third-year Spanish program, provides opportunities for 300-level students to interact with Spanish language and Latino culture outside the classroom. She also introduced the first service-learning program in the division of Spanish and Portuguese studies.

Quote: “Maria is the best! She’s an adviser and very professional and organized but is also very warm and comforting.” — Summer Institute participant Kalya Welch

Degrees: B.E., Escuela Normal de Jalisco, 1974; B.A., University of Guadalajara, 1978; Certificate, Instituto Anglo-Mexicano, 1979; M.A., Oregon State University, 1985

James D. Clowes Award for the Advancement of Learning Communities

Recognizes a Faculty or Staff Member Who Creates Learning Communities Among Students

Stanley Chernicoff

Stanley Chernicoff

Department: Earth and Space Sciences, 24 years at UW

Courses Taught: Introduction to Geological Sciences, The Earth: Its Processes and Hazards, Geology of the Northwest

Achievements: A senior lecturer in the Department of Earth and Space Sciences and the assistant dean for academic support in the Office of Undergraduate Education, Chernicoff’s classes are popular with both majors and non-majors, and he aims to make the UW feel like a small college. To this end, he conducts a discussion group every day after class, and in 2002 created the innovative Center for Learning and Undergraduate Enrichment, a campus-wide after-hours study center where students can study in groups or attend extended class sessions. The program was inspired by study programs he helped guide while director of student-athlete academic services. He also created “Dawg Daze,” a campus welcoming event that opens every school year. For the past seven years, he has also organized and taught the University’s Bridge program, an academic offering for specially admitted students from the EOP program and the Department of Intercollegiate Athletics.

Quote: “Stan’s ability to get to know all of his students on a first-name basis is legendary. This familiarity has allowed many students, who might have remained anonymous in a large class, the ability to participate more fully in the learning community that Stan has created. I have never met a student who did not fondly remember Stan’s classes or the basics of geology that they learned there.” — Robert J. Viens, ’95, ’01

Degrees: B.A., Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 1970; J.D., University of Minnesota, 1977; Ph.D., University of Minnesota, 1980

Distinguished Staff Award

Recognizes Outstanding Service to the University by Its Staff

Jason Boyd

Jason Boyd

Department: Undergraduate Advising

On the Job: Academic Counselor Lead, seven years at UW

Achievements: Boyd’s impact on the University extends far beyond his job description. The pre-med and pre-dental adviser opens opportunities for students by inviting medical school representatives to talk with would-be doctors and by traveling to community colleges to give information to prospective pre-med students. Dedicated to enriching student life, Boyd has taken several steps to improve understanding and safety for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender students, developing a workshop for staff and Freshman Interest Groups and seminars on GLBT issues. When he came to the UW, Boyd, an “enthusiastic hockey player,” took an active role as team manager and academic adviser to the UW hockey team. He is also a member of the UWAA Multicultural Alumni Partnership Board. In 2004, he won both the Adviser of the Year Award and the Office of Undergraduate Education Dean’s Award for Excellence.

Quote: “Without Jason and the amazing work he does, hundreds upon hundreds of students would have felt overwhelmed and lost.” — Andrew Warner, ’03

Douglas Machle

Douglas Machle

Department: Classics

On the Job: Assistant to the Chair, 17 years at UW

Achievements: During his five years as chair of the Department of Classics, Stephen Hinds writes, his recurring nightmare was Machle taking a position elsewhere at the UW. Machle takes on countless roles within classics, including undergraduate advising, graduate student orientation and building management in Denny Hall (including its reroofing). He also serves as the department budget and payroll coordinator and oversees at least 100 student transactions each year resulting from a recent $3-million bequest. As a linguist, he is the ultimate resource for a classics student, speaking Dutch, German, Chinese and Hawaiian and reading French and Italian. “Doug runs the classics department,” says one graduate student, “and there is some suspicion that he runs the universe too.”

Quote: “Taking charge of whatever needs to be done and assisting anyone who needs help, … Machle has been one of the friendliest, most dedicated, and helpful people I’ve ever met, and I know from conversations with my fellow students that they all feel the same.” — student Joseph Groves

Sterling Luke

Sterling Luke

Department: Physical Plant

On the Job: Mason/Plasterer, 15 years at UW

Achievements: Noted for his positive drive to “get the job done, and done right,” Luke has amazed members of the pollution prevention group at UW Environmental Health and Safety with his environmental stewardship. He regularly collects used pressure water, cooking grease and garbage that might otherwise drain into Lake Washington and Portage Bay, bringing the recovered substances to environmental health and safety for treatment and disposal. “As far as I can tell, this is not official policy or even encouraged practice at Facilities Services,” writes Pollution Prevention Supervisor Megan Kogut. “This is Sterling.” Luke does the dirty work of maintaining buildings and public facilities on campus, removing graffiti and even cleaning under cafeteria and medical research building trash bins.

Quote: “Sterling always gets it right. This happens because of his drive and desire to do his job in the best and safest way. His high standards not only impact each of his individual projects, but everyone around him.” — Pollution Prevention staffer John Wallace

Cynthia Fester

Cynthia Fester

Department: School of Law

On the Job: Secretary Lead, two years at UW

Achievements: The founder of the law school’s DIVAS chat group (Definitely Intelligent Very Accomplished Secretaries), she provides secretaries with quick access to commonly used documents and offers monthly staff computer training sessions. Putting the needs of others before her own, she tries to assist fellow secretaries, providing resources and helping them develop new skills. According to one secretary, Fester frequently takes work home and works weekends and holidays “because she often takes time helping us and does her own work later.” Fester also provides the entire secretarial support for the Innocence Project Northwest Clinic, where law students investigate and litigate claims of innocence for Washington state inmates.”

Quote: “She is the ‘assistant’ I have never had before and never expect to have again. She is a researcher par excellence, a superb writer and a highly creative organizer. In the many years I’ve been ably helped by hundreds of staff people, none stands out like Cynthia Fester.” — Law Professor William H. Rogers

Michael Biggins

Michael Biggins

Department: Libraries

On the Job: Slavic and Eastern European Librarian, 11 years at UW

Achievements: Some professors hail Biggins as “the best Slavic librarian in the country” and say they have the evidence to prove it. He is credited with UW Libraries acquiring the largest collection of Baltic publications of any university library in the U.S.-some say it’s the best collection outside the Baltics. UW Libraries recently surpassed the Library of Congress for its Latvian publications, a feat accomplished largely due to Biggins, who convinced the Latvian Studies Association to donate a 12,000-volume collection. Holding a doctoral degree in Slavic languages and literature, he also is an affiliate professor in the Slavic department, teaching translation courses. Biggins is also trying to establish a Slovenian Studies Center at the UW.

Quote: “Michael is a ‘full service’ librarian who goes well beyond our most ambitious expectations, makes a discernible difference in the lives of the people he serves, and is universally admired. Through his outstanding efforts, the Libraries’ Slavic and East European program is the envy of the nation.” —Librarian Joyce Ogburn