If sports medicine had been around in 490 B.C., Pheidippides might have been able to join his countrymen in a victory celebration. Instead, he suffered the ultimate sports injury—death.

A Greek courtier, Pheidippides ran 26 miles from the plains of Marathon to Athens to carry the news of a victory over the Persians. Under tremendous strain, he collapsed and died. While runners go the same distance today in our modern marathons, most are better prepared for the challenge.

Sports medicine research has helped prevent a rerun of the first marathon, which is why our current fitness boom hasn’t had such deadly repercussions. In the past 30 years, there’s been a huge increase in the number of people who seriously engage in sports of one kind or another. In 1966 there were only 12 marathons available in the U.S. with only 1,500 lonely long distance runners around to participate. By 1978 there were 320 marathons, with more than 60,000 participants.

By the 1980s, prestigious races such as the New York Marathon had to resort to a lottery to limit participants. The Boston Marathon, which used to require all entries to have at least one three-hour marathon under their belts, had to lower its qualifying time because so many new, fast runners were crowding the field. Today, fitness-minded Americans continue to spend $3 billion to $4 billion a year on shoes, rackets, balls, Stairmasters, Soloflexes and other exercise and sports equipment.

Physical fitness has charisma—the human body lives to move. And there is no doubt that enhanced physical fitness has improved our quality of life and contributes to our longevity. The downside is we can now live longer with the aches and pains brought about by our passion for sport. While it’s true that the human body lives to move, the human body balks at moving too much, too soon with inappropriate equipment and improper training.

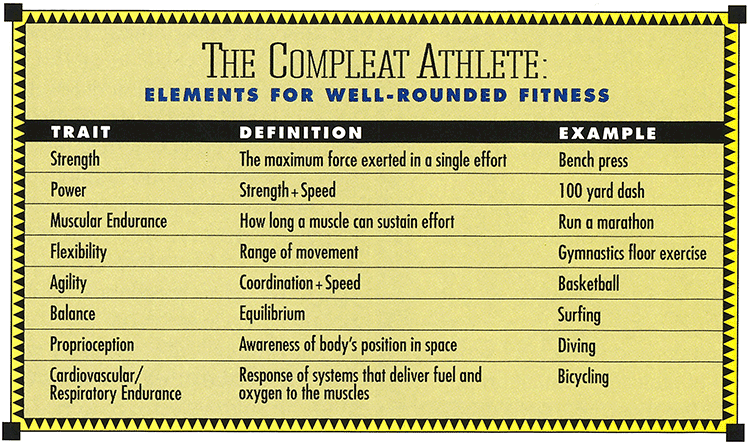

We all know friends who claim that, since they’ve started running, they’ve never been in such good shape. They often say this while hobbling along, babying a sore knee or acute Achilles tendonitis. The truth is, being physically fit involves more than just a healthy cardiovascular system or the ability to pump iron. There is a combination of physical traits that needs to be developed to achieve total fitness. Unfortunately, most weekend warriors develop only a few of these elements. This can lead to injuries that are, for the most part, preventable.

“Most sports injuries come about from a combination of overuse, an inappropriate training schedule, poorly fitting or unsafe equipment, environmental factors and faulty technique,” says Dr. Carol Teitz, orthopaedic surgeon and associate professor of orthopaedics and sports medicine at the UW School of Medicine. Teitz, who wrote the book, The Scientific Foundation of Sports Medicine, has studied a range of athletes and artists, from football players to ballet dancers.

“Other problems develop when an athlete is not strong structurally for his or her sport, or is biomechanically unsound,” she continues.

Teitz, who studied dance as a college student, became interested in the demands that dance and other performing arts place on the human body. In addition to working with ballet dancers, Teitz has treated musicians and other performers who rely on their bodies.

Like athletes, performing artists are subject to overuse injuries and damage to delicate joints because of improper technique, poorly fitting “equipment” and unsafe environments.

“I once had a patient who played a concert bass and had terrible shoulder pains,” she says. “He happened to be smaller than average and bowing and fingering created a terrible strain on his upper back He decided to switch to the cello.”

Her work with performing artists is relevant to other types of athletes as well. In a recent study of stress fractures in ballet dancers, Teitz and her colleagues came up with a warning for all female athletes.

“We found that a combination of strenuous exercise (more than five hours per day), plus a history of amenorrhea (cessation of menstrual periods) in excess of more than six months, was common in all of the dancers who had stress fractures,” she says. “We suspected that long periods of amenorrhea interfered with normal bone turnover (the process of reabsorbing old bone and laying down new bone). This dramatically increased their susceptibility to stress fractures.

“Just remember my last name. It's the acronym for appropriate treatment: Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation.”

Dr. Stephen Rice

“Other female athletes with this combination of risk factors are equally vulnerable to stress fractures and would be wise to drop back their training schedule to allow their bodies time to rest and repair.”

As an orthopaedic surgeon (or “orthopod” in sports med-speak), Teitz appreciates the changes in surgical technique and rehabilitation theory that have greatly speeded up the recovery after injury. At the 1984 Olympics, gymnast Mary Lou Retton competed only six weeks after arthroscopic knee surgery, yet she became the first American ever to win an individual, all-around gold medal.

“Before, with a knee injury, you were looking at a major operation, with large incisions that had to heal, at least five days of hospitalization, and lots of time spent in rehab afterwards,” Teitz says.

“Now, rehabilitation starts at the time of diagnosis. With the advent of arthroscopic surgery, which can be done on an outpatient basis, the patient only has to deal with three very tiny incisions, and can begin using and strengthening the repaired joint almost immediately.”

Of course, if Dr. Stephen Rice had his way, you wouldn’t need rehabilitation therapy as often because you would be wise enough to “prehabilitate.” Rice, a former physician for the UW football team and part of the UW sports medicine faculty since 1977, is a crusader for prevention and management of sports injuries.

Prehabilitation means you get in shape before you start to seriously exercise. Remember the physical traits that lead to overall fitness? Using a well-rounded conditioning program, with various exercises that allow you to develop each of those traits, you can significantly improve your performance in your favorite sport.

Cross-training may be a fad, but it pays off for runners in the weight room and football players in ballet classes. Good preparation will allow you to enhance your athletic performance, decrease your risk of injury, decrease the severity of your injury should you get hurt, and allow you to recover more rapidly after injury. If Pheidippides had had a few more training miles behind him, his first marathon might not have been his last.

Although Rice has worked with athletes of all ages, his particular concern is with preventing injuries in young athletes. In 1978, he developed a comprehensive, nationally recognized program called the Athletic Health Care System that emphasizes cooperation between parents, students, coaches, trainers and the school system to provide the safest level of athletic competition possible. Rice also teaches a basic sports medicine course through UW Extension.

When those injuries do occur, prehabilitation allows an athlete to quickly treat the damage and recover.

“It’s relatively easy to assess an injury to determine if it’s okay to continue to participate,” he says. “You examine the injured area first by observing and then by feeling for swelling and pain. Then check the range of pain-free motion and strength, and determine the stability and general function of the injured area. Finally, you test the function of the injured area specific to the sport. The severity of your injury is dependent of each of these factors. But no matter how minor the injury seems, you should initiate first aid immediately.

“The most important thing is to control the swelling which occurs after injury and causes further tissue damage if left unchecked,” Rice continues. “Just remember my last name. It’s the acronym for appropriate treatment: Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation.”

Appropriate treatment for sports injuries is the key for athletes at all levels of competition. And that treatment should include sports psychology, says Dr. Steven Bramwell, Husky football team physician for the past 16 years and founder and medical director of the Washington Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Clinic in Kirkland.

Physical injuries are sometimes easier to cope with than the psychological depression you may face when injuries take you off the playing field. His work with the football team has shown him that perhaps one of the hardest things an athlete may have to bear is coming back after a severe injury.

“It can be devastating, no matter at what level you compete,” says Bramwell, who played football under Jim Owens and was a member of the Academic All-American Hall of Fame. “For someone who has high goals, and has so much time invested in trying to attain these goals, a major injury can be a severe emotional setback.”

Of course, he continued, highly motivated individuals are quite dedicated to their rehabilitation and can be counted on to follow a treatment schedule quite faithfully—sometimes too faithfully.

“Like anyone trying to get well, they sometimes tend to push it,” he says with a slight laugh. “We have to hold them back—for example, if we give a player an exercise to do for 10 repetitions, we have to make sure he’s not trying to do it for 100.”

Bramwell is well-acquainted with the physical and psychological trauma of serious injury. In November 1991, he suffered severe injuries from a plane crash. He had extensive injuries to his face and head, suffered 11 fractured ribs and had damage to his lungs and hands.

“I was lucky to be around the 1991 Husky Rose Bowl Team when I was rehabilitating,” he says. “Their spirit and general attitude was an inspiration to me.

“The experience also gave me a little more empathy and understanding for what athletes go through when they suffer a severe, perhaps even career-ending, injury,” he adds. “And it’s very rewarding anytime an athlete comes back after an injury, it’s what makes it all worthwhile.”

Whether your goal is a first place finish in the Ironman Triathlon or just to make it all the way around Seattle’s Green Lake, UW sports medicine experts say you must treat your body with respect and care. The phrase “personal best” means more than just a faster time or a further distance—it means to champion the athlete within.

Sports injuries can happen to just about any part of the body in just about any sport. Most of us will likely incur one or more of the following sideliners as we exercise and compete: sprains, strains, tendonitis, torn cartilage, shin splints, baseball or volleyball finger, skier’s thumb, road rash (or road raspberries), blisters and deep bruises. Most of these can be treated with common aspirin and RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevation).

Many of these injuries happen to the soft tissues, the ligaments and tendons that attach our muscles to our skeleton and provide us with an amazing range of motion. The problem with these injuries is that they take a lot longer to heal because the blood supply to ligaments, cartilage and tendons is extremely limited which retards the repair process.

Tissues with a good blood supply, such as bone, muscle and skin, usually heal completely and may be even stronger post-injury. But ligaments and tendons often remain weaker after an injury and may permanently affect the stability of the joint. You may notice that you have a tendency to sprain the same ankle repeatedly.

Certain joints are more vulnerable to sprains and strains as well. For example, your shoulder is the most mobile joint in your body because it has little bony stability. Activities such as throwing, swimming or wielding a tennis racket can place a lot of strain on this intricate joint, particularly if it is suddenly overused (the first softball game of the season or your form is a little off.

Knees are also candidates for premature aging. They take the punishment for all weight-bearing sports, from aerobics to weightlifting. Because the knee’s stability depends on how the foot is planted, well-fitting, appropriate shoes and a safe surface are essential to avoiding injury. Extra shock absorption for sports that involve running also helps.

Although some people may be physiologically more prone to develop certain sports injuries, many of the sprains and strains of being a jock can be prevented by a thorough warm-up before strenuous exercise and cooling down gradually afterward. Slow stretching (not bouncing) before any type of sport helps warm the muscles and wards against sudden pulls and tears. Some athletes like to warm up by riding a stationary bike or lightly jogging. Athletes who work their upper bodies (pitchers, swimmers, rowers) should concentrate on stretching and warming up their shoulder muscles.

Cooling down should become an important part of your workout as well. Stretching, walking and other light movement will help your body return to normal. If you experience joint tenderness, you may wish to ice the area briefly and take aspirin or another anti-inflammatory agent.