The Jacob Lawrence legacy The Jacob Lawrence legacy The Jacob Lawrence legacy

Twenty-five years after his death, the noted artist's impact as a chronicler of the Black experience lives on through the efforts of local arts institutions.

By Rachel Gallaher | March 2025

Despite his celebrity, Jacob Lawrence was known as being humble, generous and hardworking—someone who spent time in his studio every day, eagerly visited school classrooms and became involved in the communities in which he lived. Most of his life was spent on the East Coast, mostly in New York, but in 1971, Lawrence received an offer for a tenured professorship from the University of Washington School of Art. At age 54, exactly 30 years after his notable emergence, Lawrence and his wife, fellow artist Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, left the epicenter of the American art world and headed to the Pacific Northwest.

“Lawrence had started putting out feelers for opportunities and positions pretty quickly after the wake of the 1968 campus protests that led to the formation of many Black Student Unions and the fight for the desegregation of higher education,” says Juliet Sperling, a UW assistant professor of Art History and the Kollar Endowed Chair in American Art. A historian of 19th-century American art, Sperling teaches broadly, she explains, “but my research area is more narrowly focused on art from, and artists that died, before 1900. Jacob Lawrence wasn’t somebody I was researching before I came to UW.”

Sperling arrived on campus in 2020. At the time, Lawrence’s legacy was especially palpable. Three years earlier, the Seattle Art Museum had shown, for the first time in decades, “The Migration Series” as a whole. A year after Lawrence completed the works, in 1941, they were purchased by New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. Because there was no straightforward way to divide the series, the latter museum took the odd-numbered panels, while the former took the even-numbered ones. In 2017, in a celebration of the 100th anniversary of Lawrence’s birth, the two institutions arranged for the series to be shown in its entirety, and Seattle, as Lawrence’s home for the final 30 years of his life, was an obvious stop. Displayed in Seattle Art Museum’s Gwendolyn Knight & Jacob Lawrence Gallery, the exhibition drew large crowds, and an interest in the artist, and his legacy, was sparked anew.

- Jacob Lawrence in 1941, photographed by Carl Van Vechten. Courtesy of the Carl Van Vechten Estate, 1966.

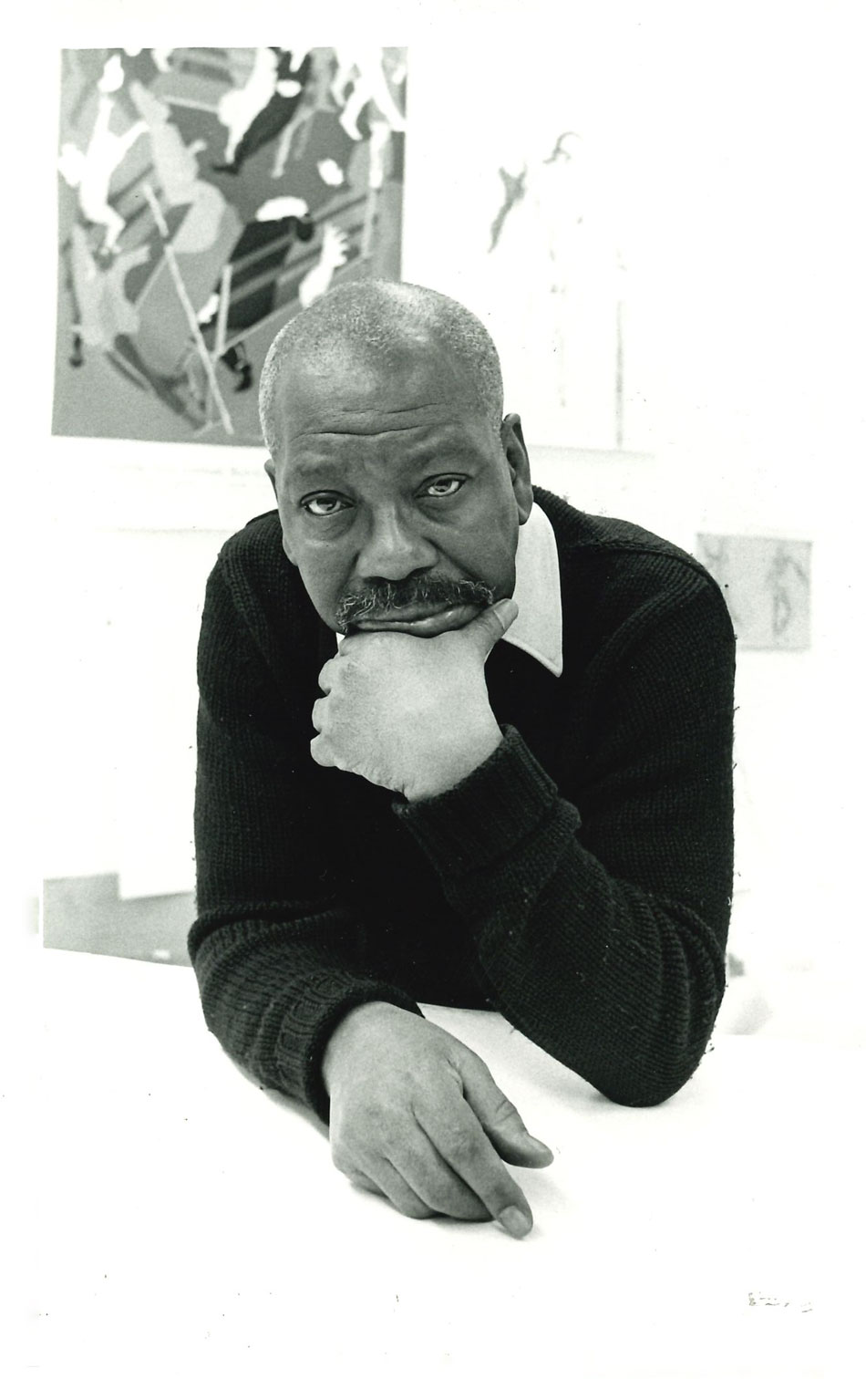

- Jacob Lawrence in 1983, photographed by Joe Freeman for the University of Washington.

While Lawrence’s talent and creativity are irrefutable, locally, his legacy is steeped in his hardworking nature, unpretentious attitude and generous spirit.

“Jacob Lawrence was nationally famous following the exhibition of his ‘The Migration Series,’” says Jamie Walker, ’81, a professor and former director of the University of Washington School of Art + Art History + Design. “It would lead him to amazing things, but I don’t think he was someone who loved or needed the limelight. His work was his passion.”

“He’d had enough of New York,” recalls Seattle-based multimedia artist and photographer Preston Wadley, ’75, ’77, who studied under Lawrence during his time at the UW. “Growing up there, he experienced that whole dog-eat-dog scene for long enough, and he got to the point where he didn’t need to be there—his dealers could handle his work for him. And he liked teaching. He taught me that you can be famous and still be a nice guy.”

In 2020, Walker, who stepped down from his directorship at in June 2024 but still teaches in the School of Art + Art History + Design, suggested that Sperling helm a seminar about Lawrence. In early 2021, “Art and Seattle: Jacob Lawrence” appeared on the course list. “Jamie said, ‘Why don’t you teach a class about him for deep context, along with the promotion of his work?’” Sperling recalls. “I expected to teach a one-off class but ended up finding a secondary area of research.”

“I consider it a strand, all of these things running through my life...I don't separate them.”

Jacob Lawrence

According to Sperling—who led her students in the research and writing of a book of essays titled “Jacob Lawrence in Seattle”—the latter half of Lawrence’s career, namely, the time he spent in the Emerald City, has been largely ignored, truncated or dismissed by critics and art historians. It seems that the Seattle years are seen as a footnote to his lionized beginnings in New York.

In 1941, at just 24 years old, Lawrence opened a solo exhibition at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery in New York’s Greenwich Village. A raw and emotionally arresting showcase of 60 painted panels depicting the post-World War I northward relocation of African Americans from the South, “The Migration of the Negro” (now simply known as “The Migration Series”) would catapult Lawrence to national stardom. Painted in a cubist style using a selective palette—black and brown, rusty red, marigold yellow, teal green, shades of blue—each scene was captured on a canvas measuring 12 by 18 inches, making them sizable enough to catch a viewer’s eye but also requiring a certain amount of closeness to experience fully.

Already a recognized talent in Harlem, where he had lived and studied for a decade, Lawrence’s showing at Downtown Gallery (known for its dedication to living artists, especially creatives such as women, immigrants and Jews) and its resulting contract made him the first African American artist to be represented by a major commercial gallery in New York. The same month of Lawrence’s opening, “Fortune Magazine” ran a multi-page spread about him featuring photographs of 26 of the series’ panels. It was a pivotal moment that would cement the early-career artist as one of the most promising creative voices of the 20th century, and an honest chronicler of the Black experience in America.

Lawrence was commissioned for a celebration of the United States’ bicentennial 1976. He created “Confrontation on the Bridge,” depicting unarmed protestors in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches for African Americans’ voting rights. When they reached Selma, the civil rights marchers were brutalized by police with clubs and tear gas on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society, NY.

“For a lot of art history, they see [the move to Seattle] as the end of his career,” Sperling says, “but mathematically it’s actually the mid-point—he spent the next 30 years making art until his death [in 2000] at age 82.”

That later work, such as the additions to the “Builders” series and the “Hiroshima” paintings (1983), is just as visually striking as his previous paintings, tinged with a slightly brighter dynamism and sense of softness that seems to come with the passing of years. Themes remain consistent and include struggle, hard work, social justice, community and personal freedom. During tenure in Seattle, Lawrence branched out into other creative forms, including public art and children’s books. His large-scale, 1979 mural titled “Games” was originally made for the Kingdome sports stadium but was removed upon the arena’s demolition in 2000. It is now on display at the Seattle Convention Center. Another piece by Lawrence, “Theater” (1985), hangs in the West Lobby of Meany Hall, in good company with works by glass artist Dale Chihuly and Guy Anderson’s “Sacred Pastures” (1978).

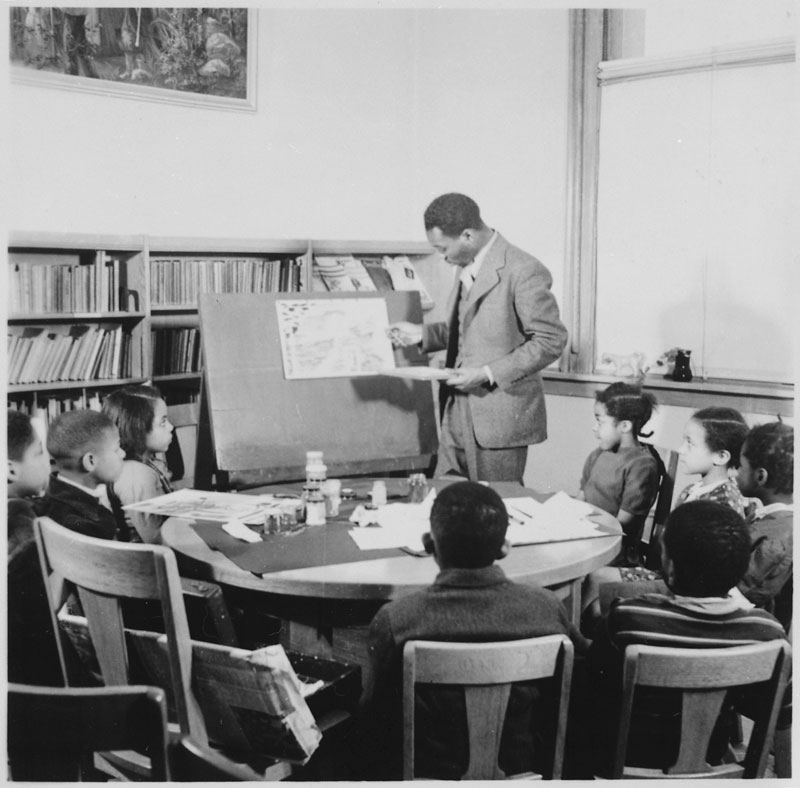

Jacob Lawrence gives a demonstration at Lincoln School. Collection H: Harmon Foundation Collection, 1922 – 1967.

Lawrence always saw himself as a New Yorker, but, as noted by colleagues, students and fellow artists, he settled nicely into his Seattle life, embracing his role as an educator and mentor—without any ego.

“From all I’ve seen in the archives and from talking to people who knew him, he was an incredible man,” says Sperling. “He was beloved by students, active in public school visits and involved in the community at large.”

“He was very positive and supportive,” confirms Wadley, who attended the University of Washington for graduate school based on Lawrence’s presence. “I applied to two schools: University of Washington because of Jacob Lawrence, and the Nova Scotia School of Art and Design for Robert Frank. I got into both, and I was already in Oregon, so it was easier to move to Seattle. My respect and admiration for both artists was the same, so I wasn’t losing anything by that choice, but it changed my life, of course.”

Wadley arrived in Seattle in the early ’70s and joined a cohort of talented young artists, including Michael Lucero, Mary Ann Peters, Sherry Markovitz and Barbara Earl Thomas. Lawrence was Wadley’s adviser. “My area of focus was painting, but I graduated without actually making a painting,” Wadley says with a laugh, noting that he “filters everything through the eye of a photographer.” Despite a difference in preferred mediums, Wadley took a lot away from his studies under Lawrence, who, he recounts, was generous with his time and expertise.

“He had a great wealth of art history knowledge, but he wasn’t a name-dropper,” Wadley says. “If you asked him questions in your history classes, he was open with his answers because he actually lived through those periods he was talking about and he knew the people involved.”

For Lawrence, there seems to have been no “before” or “after,” no hierarchy of where he spent his life. During the research process for “Jacob Lawrence in Seattle,” one of Sperling’s colleagues, Morgan Bell, ’07, ’10, ’11, discovered a recording of the previously unpublished 1978 Distinguished Faculty Lecture that Lawrence gave at Kane Hall. (It was made available to the public for the first time through the project.) At the beginning of his lecture, Lawrence presented a new painting, “The Studio,” that shows him working in his Seattle atelier, with a tableau of 1940s Harlem just outside the window. “I consider it a strand, all of these things running through my life,” he says at one point.” I don’t separate them.” It’s a nod to his approach, his view of his place in the art world and the greater tapestry of history. “You can see where I am in this moment,” he said of “The Studio,” hinting at the multitudes within him, the recognition of history—not just of great artists, but the average men and women who helped pave a path throughout the decades to make his success possible.

Lawrence taught at the UW until 1986, when he retired. In 1993, the School of Art named its first-floor gallery in honor of his impact on his students and the greater community. Despite its legendary namesake, the Jacob Lawrence Gallery went through some rough patches, with meager budgets and a dated, ramshackle presence.

“It wasn’t that dynamic at the time,” Walker, the former art school director, recalls of the years after the rebrand. “The programming didn’t feel professional, the lighting was bad. … We received feedback from the Black arts community saying that it was an embarrassment to the legacy of Jacob Lawrence.”

When Walker was announced as the next director of the School of Art + Art History + Design in 2013, he put the revitalization of the gallery at the top of his priority list. The school created a director position for the gallery and filled it with noted art historian and Frye Art Museum curator Scott Lawrimore.

Painted in 1990, “On the Way” shows a city scene, African Americans moving through the streets in bold colors and flat shapes. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Resident Associate Program, © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society, NY.

“We worked it out that he would take on a space that would honor the legacy of Jacob Lawrence and uphold his values as much possible, while still being student-centered,” Walker says. “On a shoestring budget, Scott was able to tidy up the space a bit and put together significant programming that elevated the presence of Lawrence right around the time ‘The Migration Series’ started to travel.”

One of Lawrimore’s projects was the launch of the Jacob Lawrence Legacy Residency, which continues today and is open to Black artists from around the country at any stage in their career. The recipient holds residency in January to develop new work, followed by a February exhibition during Black History Month.

It was a pivotal moment that would cement the early-career artist as one of the most promising creative voices of the 20th century, and an honest chronicler of the Black experience in America.

Lawrimore headed up the gallery through 2017, then moved on to pursue other projects. His replacement, Emily Zimmerman, continued to evolve the gallery’s mission and offerings with a focus on increased support for BIPOC artists, including an annual curatorial fellowship for BIPOC graduate students. She also served as editor of a biannual print journal, titled MONDAY, that aims at rethinking approaches to arts criticism, and extended the potential of the Legacy Residency. The role includes supporting hundreds of undergraduate and graduate students who exhibit in the gallery. Zimmerman left in 2022 for an opportunity with Arthur Ross Gallery in Philadelphia, and in spring 2024, the School of Art + Art History + Design announced Jordan Jones as the gallery’s next director and curator.

“I was lucky to inherit the newly renovated Jacob Lawrence Gallery space with the start of my tenure,” Jones says. “The new space continues our work to provide a professional-level exhibition space within the School of Art + Art History + Design. It has physically moved from one side of the art building to the other, giving it pride of place and more visibility on the first floor.”

Although it took a while—initial fundraising efforts started strong but flagged when the COVID-19 pandemic hit—the renovated Jacob Lawrence Gallery, designed in partnership with local architecture firm Mithun, opened in spring 2023. Funded partly by the Provost’s Office and the College of Arts & Sciences Dean’s Office (which covered two-thirds of the renovation expenses) and partly by private donors, the new space features bright white walls, original polished concrete flooring, and security and climate control systems that meet American Alliance of Museums standards, so works from other galleries and museums can be displayed on loan.

“It’s been a journey, but the gallery is in place and it’s here to stay for a long time,” Walker says. As visitors enter, they pass a large, in-wall display that includes an overview of Lawrence’s life. “We want people to understand who Jacob Lawrence was, why he was important, and that he chose to spend the last 30 years of his life here.”

“[Jacob Lawrence] shaped a generation of artists coming through the BA and MFA programs at the school,” says Jones, who is currently developing a Jacob Lawrence Mapping Project to better understand the lasting impact on his work and presence in the community. “This project will mark the key sites throughout UW and Seattle that have connections to Lawrence or are places where you can find his work and will collect oral history interviews with the folks who knew him to capture the lasting impact he has had on individuals in our community. This project comes out of my own experience of constantly bumping into a new Lawrence work or encountering someone with a Lawrence story to share while getting settled in the city.”

“The Studio,” a 1977 self-portrait by Jacob Lawrence, features his Seattle home studio with a window looking out to Harlem. Courtesy of Seattle Art Museum, © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society, NY.

At the beginning of 2025, Seattle Art Museum closed “Jacob Lawrence: American Storyteller,” a focused exhibition that brought together works from SAM and local collections and highlighted the artist’s narrative skill (via figurative work) at a time when abstraction ruled the scene. Painted in Lawrence’s spatially flattened style, the works—many dating to the second half of his career—capture the heart of his practice, which relies on story. Each of his pieces holds hundreds of story threads that culminate into something larger: a visual reckoning of themes, including family, community, history and self-determination. With a single painting, Lawrence is able to capture the viewer’s imagination, leading them along different narrative tributaries with roots that extend back hundreds of years. Its figurative nature and simple scenes of daily life—families walking down the street, people gathering or participating in sports—render it more emotionally relatable than, say, an abstract geometric sculpture.

“I think Jacob’s Lawrence’s work has seen a resurgence in popularity because he was interested in reflecting the realities of the society he lived in in a way that was very direct,” says Walker. For Seattle, a relatively young city with a less far-reaching visual arts scene than New York or Los Angeles, that Jacob Lawrence chose to remain here until his death feels like a stamp of approval.

“That has to do with our position in the American art world,” Sperling says. “Incredible art has been coming out of the Northwest for millennia, but historically, it hasn’t always been recognized by the broader art world. Him choosing Seattle to make work in for the rest of his life says a lot.”

For Wadley, Lawrence’s appeal has never waned. When asked why he thinks the late artist’s catalog still resonates so deeply with people, his answer is simple: “Because it’s good,” he says. “Look, as Duke Ellington would say, ‘There’s no new music or old music, only good music,’ and it’s exactly the same with art.”