On a beautiful May morning, Sarah Reichard wondered who could be calling her at 5:30 a.m. She had no idea that the ringing phone was the first warning that her professional life was being turned upside down.

Reichard’s colleague, Linda Chalker-Scott, left a hurried message on the answering machine: “The lab is on fire and I’m going down there.” Reichard remembers feeling sorry about the lab fire, “but the importance didn’t really hit me,” she says. She leisurely fed the cat, then called Chalker-Scott’s husband to ask how bad it was. “He said to turn on the TV,” Reichard recalls. “The first thing I saw was the image of what looked like my office, up in flames.”

Sometime after 1 a.m. on May 21, 2001, members of the Earth Liberation Front (ELF), an underground “eco-terrorist” group, broke into Merrill Hall, the oldest and largest of several buildings at the Center for Urban Horticulture. Part of the College of Forest Resources, the center sits near Union Bay and the Montlake parking lot, a testament to the region’s love of gardening, since all the buildings were financed with private funds.

TV coverage of the fire.

That night, the ELF visitors left a calling card—a bomb made from a bucket of gasoline, a child’s rocket and a kitchen timer. A little after 3 a.m., it exploded in a giant fireball.

The resulting fire burned Merrill Hall beyond repair; severely damaged the Elisabeth Miller Horticulture Library; ruined the work space of 50 research faculty members, graduate students and staff; destroyed one-quarter of the world’s population of an endangered plant species; consumed decades’ worth of academic literature; closed cooperative extension offices; and melted hundreds of slides, including some illustrating the step-by-step recovery of Mount St. Helens.

“It’s still hard to believe that something like this happened to us,” says Reichard, an assistant professor of ecosystem sciences. “We teach about horticulture and sustainable landscaping and conservation and restoration. Who would want to destroy that?”

Today, visitors to the center can see winter color in the Goodfellow Grove, the McVey Courtyard and the Seattle Garden Club’s Entry Garden. They can see people writing notes about the various flowers and grasses in the Soest Garden. People are using the “new” Elisabeth Miller Library and the Hyde Herbarium. The Plant Answer Line is ringing, a Master Gardener is answering a garden pest question; there might be a public lecture sponsored by the Northwest Horticultural Society in NHS Hall; and students are attending classes in restoration ecology in Douglas Hall.

“We teach about horticulture and sustainable landscaping and conservation and restoration. Who would want to destroy that?”

Sarah Reichard, assistant professor of ecosystem sciences

That the center would recover so well would have surprised Reichard on the day of the fire. When she neared the center, three hours after the explosion, 50-foot flames were still shooting into the sky. She found fellow professor Chalker-Scott, and they stood, horrified and unbelieving. “For academics, this isn’t just an office. It’s our world,” Reichard says. “A huge portion of my life is in my office and my lab.” When he heard the news, H.D. “Toby” Bradshaw, a plant geneticist who worked at the center, knew right away why the building was on fire. “I’ve been around enough of these terrorism events to recognize the signature,” he says.

Bradshaw, who has since been appointed associate professor, caught the unwanted attention of radical environmental groups for his work with the genetics of poplar trees. That research, he says, is only a small part of his work, which also includes researching the evolution of monkey flowers and experimental genetics in a mustard plant. He works with poplars because they grow quickly, making them easy to study. He’s looking for genes that, for instance, control the tree’s growth, repel pests and create fewer knots in the wood. As a practical application to his research, plantations of fast-growing, disease-resistant poplar trees can be used to supply lumber and paper as an alternative to logging forests.

Groups such as the ELF oppose genetic engineering of trees, believing that “You cannot control what is wild,” according to the group’s motto. In taking responsibility for the attack, an ELF message claimed that Bradshaw “continues to unleash mutant genes into the environment that is certain to cause irreversible harm to forest ecosystems.”

Bradshaw was using only traditional breeding methods in his own research, though he had about 80 genetically engineered aspen trees, obtained by collaboration with a colleague in Oregon, growing elsewhere at the center. He has never released a genetically engineered plant of any kind into the environment. All such releases require special permits from the state and federal governments. Of the ELF, he says, “They’re unbelievably ignorant about science. We’re not dealing with the brightest pennies in the fountain, here.”

In the courtyard of the Center for Urban Horticulture are (from left) Professors H.D. “Toby” Bradshaw and Sara Reichard, and Center Director Rom Hinckley. Photo by Mary Levin.

Asked to characterize the ELF for a TV reporter, Bradshaw described the group as the Taliban of environmentalism. “They’re fundamentalists who believe that their world view is so correct that it needs to be imposed on everyone,” he says. “And if you don’t subscribe to it, they’ll burn you out.”

Professor Tom Hinckley, the center’s director, arrived at the scene about 6:30 a.m. “I knew Toby’s work, or alleged work, was not well received by some extremist groups. It seemed really obvious,” he recalls. He found the captain of the fire crew and explained his suspicions. Despite investigations by the FBI, ATF and local police, no suspects have been arrested to date.

By afternoon of that first day, the recovery effort was already under way. A makeshift headquarters was set up in the greenhouse. Firefighters had been able to put tarps over most of the library’s collection and, once the immediate danger of fire was past, began hauling books and other materials out to the anxious arms of the library staff.

Community groups offered to share their space in another center building. The UW Physical Plant provided three temporary trailers for faculty and staff and a doublewide for grad students. The University, which is self-insured, spent more than $1.2 million in efforts to help recover materials, arrange for interim work and office space, restore books, demolish the building and provide emergency resources.

On the third day, a few people were allowed into their offices for 15 minutes. “It was surreal,” Reichard reports. The humidity inside the water-soaked building was unbearable. Drenched with sweat, she made her way through the blackened hallways. The paint had peeled, the walls burned through in some places. Fallen, wet plaster lay on the floor and was quickly trampled and turned into pulp.

Confronting the mess in her office, Reichard says, she faced a moment of panic. She gathered up some personal pictures, slips of paper from her bulletin board and a couple of out-of-print books. “Then I just looked around. What do you save? I really didn’t know. I started to cry,” she says. “Then I pulled myself together and just started putting things in a box.”

Volunteers started showing up immediately after the fire. They brought food, flowers, comforting words and, most important, muscle power. They carried the rest of the books and reading materials out of the library, wiped the soot off and loaded them into freezer trucks, bound for restorative treatment in California. They cleaned slides. They helped carry file cabinets and equipment, anything that could be salvaged, and heaped it into piles in the greenhouse. And they offered one thing sorely needed—affirmation that the center matters.

“Adversity tells you what people are made of. This is a good example of the stern stuff that Seattleites are made of.”

H.D. “Toby” Bradshaw, plant geneticist

President Richard L. McCormick declared that “self-appointed vigilantes” would not deter the quest for knowledge, and that the facility would be rebuilt. Newspaper editorials expressed outrage. Legislators promised funds to rebuild. And environmental groups denounced the destruction.

“President McCormick made it clear that the UW won’t tolerate this kind of attack on its faculty and the general principle of academic freedom,” says Bradshaw, who was impressed with the strong community support. “There was a similar kind of thing after 9/11. Adversity tells you what people are made of. This is a good example of the stern stuff that Seattleites are made of. I’m really proud of the University, the Legislature and the community,” he says.

But the hard work of recovery came down to the people who work at CUH. “It was just utter chaos for months,” Reichard says. “That’s what people don’t realize. They still say to me, ‘Is everything back to normal?’ Well, no. I still don’t know where everything is.” Reichard estimates that as much as 5 percent of her things might still be lost.

She did manage to save her extra-large vertical filing cabinet and all its contents. When she opens it and pulls out a file, though, a smoky odor emanates. The sooty dust that covers every file smudges her fingers.

Hinckley shows visitors some of his souvenirs: a page of slides, some melted into their plastic pockets, others blackened by smoke. A book that cost about $85, its pages bulging and crinkly and sprouting pink and yellow mold.

A charred poster annoounces a new course in wetlands restoration. Photo by Mary Levin.

Still, all is not lost. Both Reichard and Hinckley say they were able to salvage more than they expected, including the hard drives from their computers.

Reichard lost a significant chunk of the world’s population of a plant that she and colleagues are trying to save from extinction, the showy stickseed, a relative of the forget-me-not. “It’s very rare. It’s only found in one location in the north Cascades,” she says. A few weeks before the fire, staff member Laura Zybas and Greg Peterson, a volunteer, took 100 cuttings of stem tissue from the existing population and brought them back to the CUH to culture them. The heat, smoke and debris from the fire destroyed all but seven, setting the program back an entire year.

No one lost as many physical possessions as Bradshaw, whose office was a blackened shell. His 22-year collection of resource books, personal items and artwork was incinerated. But, speaking in his new lab, away from the original site, Bradshaw is struck by the irony that the attack—meant for him—has affected him the least. His computer files were backed up in a secure location, so he lost very little of his work.

“None of my data were lost. None of my seeds or DNA stocks or plants—none of that was lost. But some of my colleagues lost huge collections of slides they use in teaching, or they lost living plant material—irreplaceable things,” he says.

He even feels survivor’s guilt because his situation has improved since the fire. “Whereas, for all my colleagues at the center, their lives are immensely worse than they were before,” he notes.

From Hinckley’s interim office, a cramped 7-by-11-foot space in the greenhouse, he surmises an unseen cost, as well. “We’ve been given an extra workload. There’s your normal workload you’re expected to do at the UW, but now you have a recovery load, too,” he says. Additional tasks for faculty and staff include helping with the redesign of the building, which will employ sustainable features, and raising funds for the building. “It has turned out to be a lot of work,” Hinckley notes.

Originally up for tenure last year, Reichard’s deadline to turn in her tenure packet was extended a year. “What I really lost was time,” she says. “It wasn’t until this summer, honestly, that I felt like I was back to the point I was on May 20, 2001.”

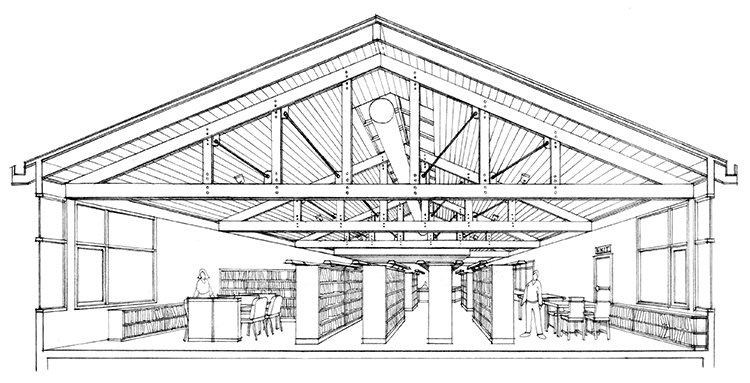

An architectural rendering of library space in the new Merrill Hall, courtesy Miller/Hull Partnership.

But despite the recovery, staff are still jumpy. “For those people who say no one’s ever been killed in an ELF action, all I can say is you should have seen those firefighters standing on the metal roof, trying to ventilate the roof and put the fire out, with fire coming out the holes,” Bradshaw says. “It’s a miracle that nobody was killed. It’s just a matter of time.”

That may soon be a moot point. ELF, which in 1990 burned down a $12 million Colorado ski resort, claimed responsibility for destroying a Forest Service research station in Pennsylvania this summer. And, in a shivery change of attitude that no one at the center has failed to note, the ELF has promised that it “will no longer hesitate to pick up the gun” in future actions.

Bradshaw says he could have predicted this. “Ultimately, the decisions that the ELF are trying to influence are not made at all by people like me. They’re made by politicians and voters. The idea that burning out my lab can somehow set back forestry on a commercial scale just shows an incredible lack of understanding about how the world works. They almost never target the ‘right’ thing, and it never, as far as I know, has the desired effect. That’s why I think you see an escalation in the level of violence in their rhetoric.”

Hinckley sees a parallel between the ELF and those who bomb abortion clinics. “First you picket, then you bomb, then you start shooting people,” he says. He’s not particularly frightened for himself. “But I’m concerned about some people who have been identified by this group.”

“Everyone dug in and showed that they were going to go through the recovery and keep the programs alive and actually see them prosper, take them to the next level.”

Tom Hinckley, director of the center

Bradshaw shrugs off concerns for his personal safety. “I’m just not the worrying kind,” he says. “There are much bigger things in the world to worry about.” Although the University has taken reasonable precautions, Bradshaw says, the cost of absolute security would be too dear. “I would never want to adopt a fortress mentality,” he says. “That’s just antithetical to how public universities should treat the citizens of their state.”

The decision to rebuild the center was made quickly, although working out the details has been an ordeal. The Washington Legislature promptly allocated $4.1 million toward replacing Merrill Hall, but it was soon apparent that that would not be enough. Eventually the University procured an additional $1.3 million, enough to construct a new building of the same size on the old foundation.

In a sense, the new building will be smaller, however, since wider hallways, an elevator, and other factors to bring it up to code will reduce usable space by about 600 square feet.

Rebuilding has presented an opportunity to rethink the design, as well. The new Merrill Hall will showcase sustainable features for demonstration and teaching. All the outreach functions, such as the library, the Master Gardeners clinic and the herbarium, will be clustered together. Private donations and special efforts—such as the sale of personalized leaf-patterned floor tiles—are helping make the new Merrill Hall a place that can better accommodate use by the public. Reconstruction is optimistically slated to begin next spring, with completion by May 2004, the three-year anniversary of the fire. For more about the rebuilding efforts or to make a donation, visit the center’s Web site at www.urbanhort.org.

On the anniversary of the bombing this spring, the center held a celebration, with speakers and guests, donated food and a generous helping of relief. “There were many times during the last year when I didn’t think we had the energy to make it,” Reichard says. “But somehow we made it a year. That really was a turning point for me.”

In the aftermath, “I expended a fair amount of energy thinking about revenge,” recalls Hinckley, but he adds that 9/11 put things in perspective. “I think you begin to realize you’ve been dealt a setback, but you’re still walking, and no one got physically hurt. Time heals wounds.” And there have been some positive aspects: the cohesiveness of the group, seeing the University’s strength in a crisis, learning that the UW Physical Plant is an amazing force, the improvements in the new building, and the faculty’s demonstrated resilience.

“I sometimes wonder where they get the energy and drive to do all the things they do,” he says, including keeping up with class loads and providing community outreach programs. “This might have been a good excuse to retire, to quit, to just drop way back in load and energy,” Hinckley says. “Instead, everyone dug in and showed that they were going to go through the recovery and keep the programs alive and actually see them prosper, take them to the next level.”

It takes a lot more than total destruction to keep plant people down.

Surviving the flames

Founded in 1984 and built with private donations, the Center for Urban Horticulture’s mission is “to apply horticulture to natural and human-altered landscapes to sustain natural resources and the human spirit.” As part of its public service, the center provides meeting space for gardening clubs and environmental groups, educational classes, demonstration gardens, and a place to come for answers: the Master Gardeners clinic on Saturday mornings, the Miller Library or the library’s Plant Answer Line.

On average, more than 12,000 visitors a year use the library, but after the fire, it was forced to close for seven months. “Every single thing needed to be ozinated to take the smell out. And the ones that were wet needed to be freeze-dried. Some needed both,” says Valerie Easton, the library’s manager. “The library was actually the most adversely affected because we are our materials.” About 15 percent of the collection was damaged beyond repair.

Last December the library staff moved as much material as would fit—the things that were most used and least damaged—into a classroom in Isaccson Hall. The rest of the collection is stored at the UW Libraries Sand Point facility.

Fortunately, the old and rare books, some of them dating to the 17th century, were the least damaged because they were housed in a special vault. The books were not singed or water soaked, although they did absorb smoke. They are currently housed in the Allen Library and are being “passively deodorized” to remove the smell without damaging the pages, Easton explains.