When author Stephanie Kallos had to take time away from writing her second novel to promote her first one, the critically praised Broken For You, she felt she needed to make a few apologies first.

She didn’t offer apologies to family or friends, though with book promotions those are always a possibility. No, Kallos went to her computer and fired off a quick note of explanation to fictional characters in her next book — to Larken, an obese art history professor and her brother Kelley, a body-building TV weatherman, among others — whose lives would be suspended while their creator attended to other matters.

Kallos does this sometimes, she says — writes to her characters to prod them into action or inquire into their affairs, as if they were beings separate from herself. Unusual, maybe, but Kallos knows a lot about fictional characters, having been several herself.

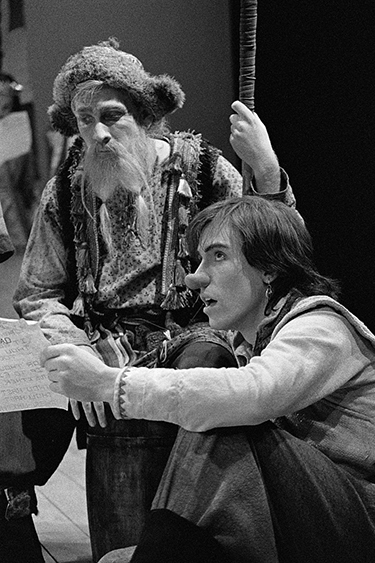

Stephanie Kallos in her back yard. At top, she performs in a drama school production of Chekov’s “The Suicide.”

She’s a former actress and a 1982 graduate of the University of Washington’s Professional Actor Training Program (PATP). She spent about 20 years acting — filling characters created by other writers with her own life’s breath — before stepping back to consider other paths. And though she has left acting behind for the life of a parent and author, glimmers of her stage past shine through her fiction. Kallos appreciates the connection; much that she learned in the theater comes in handy in her writing, she says. Kallos is but one of scores of PATP graduates who, after years or decades pursuing work on the stage or in film, have moved on to careers outside of entertainment. Though their stage days are behind them, many of these alumni say they still benefit, directly or indirectly, from skills they learned in the program.

“As an actor you inherit a tiny bit of text from the playwright and fill in the internals,” Kallos says. “That’s all that novelists do. We are responsible for the prose part of the character and the dialogue as well, but the big release you get is the ability to dive into somebody’s head. And that’s the part of acting I liked the most,” she adds. “The inner life.”

Writing fiction, she says, is like “cultivating a benign form of schizophrenia.” She says she doesn’t plan every nuance of her characters’ destinies; in fact, it sometimes seems more the other way around. “Characters come in mind and they frequently have their way with me.” The actors training she got at the UW helped make such explorations possible — understanding of a character’s “inner life” is needed as much by authors as by actors.

The PATP has been preparing young actors for entrance into the entertainment world for nearly four decades. Started in 1970 by Seattle theater icon Gregory A. Falls (who went on to found Seattle’s A Contemporary Theatre), it is an intensive, three-year M.F.A. program designed to ready students for acting careers in theater, television and film. Taught by instructors with solid professional experience, the program gives students skills in acting, voice, movement, research and analysis, and even stage combat. The program has been rated as among the best professional training schools in the nation, and accepts a mere 10 actors every year of the nearly 1,100 who apply.

The PATP has produced many working actors and theater professionals, employed from Hollywood to Broadway and virtually all points in between. “We try to create actors empowered to be artists in their own right,” says Sarah Nash Gates, executive director of the UW School of Drama. With such training, she says, they can become good craftspeople who can work collaboratively or on their own. Mark Jenkins, who runs the PATP, calls the training “the basis for a lifelong inquiry, curiosity and the discipline to keep training.”

But for every star PATP alumnus, such as Kyle MacLachlan of Sex in the City or Jean Smart of Designing Women, there are many others who ultimately veer away from acting. It’s not surprising, given the difficulty of the profession; unemployment rates in both Actors Equity and the Screen Actors’ Guild, the two main actors unions, usually run well above 80 percent.

Dwight Smith in a drama school production of “A Winter’s Tale.”

Like Kallos, 1990 PATP graduate Dwight Smith also found a different profession — he became a minister. Smith is lead pastor of the Oasis Christian Fellowship, a small church outside Seattle. And though he still does the occasional acting gig when he can — voice-overs, films, plays and commercials — his service to his congregation is more than just a day job, it’s his life.

Raised in a Christian home, Smith says he got into theater partly because it brought him social attention in high school — a tale many actors tell. But when he reconnected years later with the church, it didn’t feel like a major change, he says. “It wasn’t that dramatic in terms of my world view and Biblical view.” He says the two pursuits share a common theme of “conveying truth in a transparent manner,” which he calls “really the essence of acting.”

Smith, who calls upon skills from both the theater and the church to write occasional pieces for Drama Ministry Magazine, says that “the problem sometimes with the church is that we have decided that a lot of art with a capital A is somehow not about God.” He adds, “Anything that is truly art, from my viewpoint, is about God. True art is about God.”

If author Kallos’ exploration of fictional characters might run more deeply due to her PATP training, so too does Smith’s feel for people’s motivations in pastoral counseling. It might sound like actor-talk for Smith to say “You can’t activate a negative intention and make it believable,” but it’s a helpful way to understand human behavior. In Smith’s view, an angry, potentially abusive husband rarely intends to be so. “He’s making a choice based on some form of internal motivation,” Smith says, “and it’s the only tool he has in his box.” As a counselor, Smith says, he might ask, “What is that choice really getting you? What’s the ‘win’ in that for you?” It’s what actors and directors do when they probe a character in a play.

Dwight Smith now spends his time at the pulpit rather than in the spotlight.

Smith says his church colleagues tend to admire the interpersonal communication skills that came with his acting training. “The tools you learn in a seminary setting help you be a good theologian,” he says, “but don’t necessarily translate into being a good pastor or shepherd.”

Library science called to 1991 PATP graduate Joel Summerlin after he spent several years in the Seattle theater scene. Ultimately, he says, the negative aspects outweighed the positive in his stage life. “For any art you go through a lot of dreck to get to the good stuff. I was finding the ratio of things worthwhile to things that weren’t worthwhile wasn’t high enough.” He returned to the UW in 1998, earned a degree from the Information School and is now a taxonomist, cataloging photographic images for the Seattle-based Corbis Corporation.

“I’ll always feel glad I was an actor for a while,” Summerlin says. “It’s hard to draw lines between the things I learned in the PATP and the skills I now use in my current career, but at the same time I don’t think anything anyone learns is useless. I’m a firm believer in a liberal arts education. It’s not about using things on the job, it’s about being a well-rounded person.”

Inevitably, of course, the PATP’s range of training helps some more than others in the world beyond acting. Andrew Boyer, a 1995 graduate of the program, performed in the 1990s in New York, but was ultimately worn down by the hand-to-mouth actor’s life. Working with fellow actors in their 50s brought that into focus, Boyer says in an e-mail from London, where he now works as a securities lawyer. “I realized that it was a very real possibility that in 15 more years, when I would be 50, I could still be working hard for no pay and hoping to get noticed too. That was an unacceptable future for me.”

So he went back to school, faced down the bar exam and began his new career. The switch wasn’t easy, he says, “It’s a long path and I don’t recommend it.” And though Boyer says his script analysis skills may help him unravel the thick language of statutory law, the connection pretty much stops there. Of the many things he studied in the PATP — “the yoga, the Suzuki training, the jazz dance and stage combat, the singing and voice work, the tightrope and trapeze classes, the philosophy of connecting mind and body” — few pertain to his current work. Boyer wrote with some finality, “The PATP trains actors, and being a transactional lawyer is simply not anything like being an actor.”

If there is a hint of sadness in Boyer’s story, it should come as no surprise. Nearly any former actor will tell you, leaving the theater — packing away the well-worn makeup kit, headshot and résumé, hanging up the tap shoes — can be a heartbreaking decision. Summerlin says it well: “It was a tough time, having that realization. There was a lot tied up in that — a feeling of failure, that I made the wrong decision, what have I done?” It took some time, he says, but “Ultimately, I did make the right decision.” Still, there always remains the question: Would these former actors return to acting, given the right circumstances? Answers were mostly variations on the theme of a door that is closed just now, but perhaps not locked for good.

Pastor Smith says, “I’m doing exactly what I want to do.”

Boyer, the London-based lawyer, is still working through the emotions of his life change. “I still believe that entertaining people and lifting them temporarily out of this difficult world is a noble calling. … It breaks my heart a little if I think about my former love of theater. Maybe someday I’ll direct something,” he says.

Kallos quit acting about nine years ago. “I don’t miss it very much. The only time is with Shakespeare — that’s the only thing I ever really miss. I’m so lucky I got to play the roles I was right for.”

“When we started in the PATP,” Summerlin says, “(then-program director) Jack Clay, early on, said, ‘If there’s anything else in the world you can do, go do it.’ I think it’s pretty good advice in a lot of ways.”

He didn’t take that advice, of course. He stayed, graduated and enjoyed acting for several years, as did many others. And though it didn’t last forever, they wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

On the scene: 10 famous PATP graduates

- JOHN AYWARD, ’70: After many years lighting up Seattle stages with his characterizations, Aylward took his talents to California, where he has appeared in dozens of movies and TV shows. Most notably, he played Dr. Donald Anspaugh on several episodes of the hit TV drama ER.

- PATRICK DUFFY, ’71: A well-known TV performer for decades, Duffy is best known for his ongoing portrayal of Bobby Ewing in Dallas from 1978 to 1991. He also played opposite Suzanne Somers in the popular sitcom Step By Step from 1991 to 1998.

- LINDA EMOND, ’86: A veteran stage performer, Emond appeared on Broadway in Tony Kushner’s Homebody/Kabul as well as 1776 and Life (x) 3. She also has appeared in several TV shows, including Law and Order, Third Watch, Wonderland and The Sopranos.

- HARRY GROENER, ’76: A three-time Tony award-nominee for his performances on Broadway in Cats, the Gershwin musical Crazy for You and a revival of Oklahoma!, Groener also is known to a generation of Buffy the Vampire Slayer viewers as the evil Mayor Richard Wilkins III. He has a recurring role in NBC’s Las Vegas and appeared in such films as About Schmidt, Patch Adams and Road to Perdition.

- LINDA HARTZELL, ’73: A key participant in Seattle professional theater over the years, Hartzell has been artistic director of the highly praised Seattle Children’s Theatre since 1984. She has directed 40 plays for SCT, 33 of which were world premieres. She also is a member of the College of Fellows of the American Theatre, and was honored with a Distinguished Achievement Award from the UW College of Arts and Sciences in 1994. “Of all my awards, that’s the one I cherish most,” she says.

- RICHARD KARN, ’79: Karn played Al Borland, the wiser and more carpentry-friendly sidekick to Tim Taylor (Tim Allen) in the popular sitcom Home Improvement from 1991 to 1999. Karn took over as host of the game show Family Feud in 2002. He also hosts the Richard Karn Golf Tournament each year in the Seattle area, with proceeds going to cancer research.

- KYLE MACLACHLAN, ’82: MacLachlan may be best known for his wry, deadpan portrayal of Agent Cooper in David Lynch’s enigmatic TV series Twin Peaks and the mother-dominated Trey MacDougal in the hit series Sex and the City. MacLachlan is also known for his film roles in Dune, Blue Velvet and The Doors.

- JOEL McHALE, ’00: A former member of the troupe of Seattle’s Almost Live sketch comedy TV show, McHale is now the host of The Soup on the E! channel. He has been featured in commercials for Burger King and other products, as well as a role in the hit movie Spiderman 2.

- PAMELA REED, ’75: A veteran film actress, Reed has been featured in dozens of theatrical and TV movies, including Kindergarten Cop, Mr. Bean, Proof of Life and The Right Stuff. Reed also has appeared on many TV shows, including The Simpsons, Judging Amy and L.A. Law. Over the years, Reed has been a strong supporter of the UW School of Drama.

- JEAN SMART, ’74: After many stellar theatrical performances in Seattle and with the Ashland Shakespeare Festival, Smart embarked on a successful career in TV and movies. She has been featured in the films Garden State, The Kid and Bringing Down the House. On TV, she is best known for her roles on the sitcoms Designing Women from 1986 to 1993 and the current show Center of the Universe with John Goodman. Smart won two consecutive Emmy awards for guest roles on the TV show Frasier, and was nominated for a Tony for her portrayal of the sexy actress Lorraine Sheldon in a Broadway revival of The Man Who Came to Dinner.