Thousands of people cross UW’s Red Square on their way to classes, meetings or for an afternoon stroll. They sprint or saunter, but are they conscious of the bricks beneath their feet or the buildings that frame their journey? “Architects speak to society. We use space and materials to create a sense of history combined with the present and possible visions for the future,” says David McKinley, ’53, co-architect of Red Square. “We’re interpreters for who people are and what they might become.”

UW architecture has been designing dreams for a century. The program welcomed its first class of a dozen students in 1914. Now named the College of Built Environments (CBE), more than 250 graduated in summer 2014. CBE consists of four departments—architecture, construction management, landscape architecture, urban design and planning, as well as the Runstad Center for Real Estate Studies. Students also enjoy expansive study-abroad opportunities and hands-on learning through the Furniture, Storefront and Neighborhood Design/Build Studios.

Graduates have made their mark on skylines around the globe, including the enduring legacy of New York’s World Trade Center by Minoru Yamasaki, ’34. The most indelible influence, however, is University of Washington architecture’s shaping of Northwest soul and style. A family visit to the Pacific Science Center’s arches or Seattle Aquarium, a romantic dinner at Canlis restaurant or concert at KeyArena: they all happen within the framework of UW creativity.

“People often don’t consciously understand how much space and the meaning of architecture influences their daily lives. There is a humanistic side to architecture that is largely unknown,” says David Miller, chair of the UW Department of Architecture. “We seriously consider the complex array of social, ethical and ecological issues in order to enhance the human condition.”

“UW architecture began 100 years ago as a small school that has grown to include many disciplines with national and international focuses,” adds McKinley. “It’s absolutely marvelous!” A century later, the world looks different but the vision remains the same: create connections by design.

***

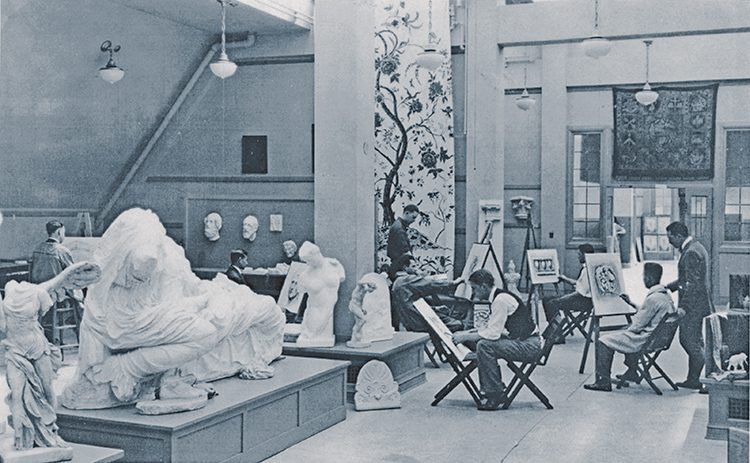

Students practice in the Main Freehand Drawing Studio in Education Hall, later renamed Miller Hall, in 1925.

The UW campus itself is a testament to the architecture department’s evolution. In fall 1914, Carl F. Gould taught UW’s first-ever architecture lecture, thus launching the department. It focused on the residential house because it was offered as part of the home-economics program.

If home is where the heart is, Suzzallo Library became the UW’s center. Gould, representing the firm of Bebb and Gould, was hired as principal architect in 1915 to create the layout that became known as the Regents Plan, from which the campus grew. Gould envisioned the library as the “soul of the university.” Opened in 1926, it was placed at the central plaza now known as Red Square. From the north, it connects the liberal arts quad with its iconic Yoshino cherry trees to the science quad on the south encircling Drumheller Fountain.

Gould was ultimately principal architect for 18 UW buildings, using the Collegiate Gothic style for which the campus remains known today. Many buildings remain in use such as Anderson, Eagleson and Raitt Halls plus Henry Art Gallery. Gould served as the first architecture chairperson from 1915-1926, a time of expansion for the campus and the department. The early curriculum was heavily influenced by France’s École des Beaux-Arts approach, which emphasized classical Roman and Greek styles.

Suzzallo Library, the jewel of the UW campus, under construction during the 1920s. Pictured with it at top are a student painting by T.T. Matsumoto and a classroom scene from the 1957-58 school year.University of Washington Libraries Special Collections

“The approach to American architecture education from the 1890s to late 1930s was based on an idea of eclecticism,” says Jeffrey Ochsner, professor of architecture. “Architects sought an appropriate historical source and creatively adapted it to current projects.” Amenable to the fashions of the times, the department was molding history as well. “The influence of the UW architecture department in this region is extraordinary. I would call it hidden in plain sight because many people don’t realize the significance,” says Ochsner.

“One of the department’s legacies is a focus on local contributions,” says Kathryn Merlino, associate professor of architecture. “We’re a Pacific Rim area and we do global outreach. However, a big strength is supporting the longevity of our own environment and education at the UW.”

“The school has always changed and responded to architectural styles and movements over the course of its history,” says McKinley. “However, the education always attempts to bring out original thinking within each student. That continues to this day.” The architecture department boomed. It employed around four full-time faculty throughout the 1930s. That number jumped to 17 by 1950. Jane Hastings, ’52, remembers classes held on Saturday nights and campus barracks erected for a bursting-at-the-seams student body following World War II. Thousands of returning veterans used the G.I. Bill—1944 legislation providing educational benefits—to enroll in school.

“The University was in a state of shock. The G.I. Bill was brand new and they didn’t yet have the facilities or programming to accommodate everyone,” says Hastings, founder of the Hastings Group firm. “We learned as much from each other as the faculty. There was a wonderful sense of camaraderie.” The veterans weren’t the only new kinds of students: in her incoming freshman architecture class, Hastings was one of two women with 200 male classmates. She ultimately became Washington state’s eighth licensed, female architect.

Resources also expanded. The Urban Design and Planning Department was founded in 1941. A proper library collection opened in 1949 as a branch of the UW Libraries. “We had about 3,000 volumes to start, all organized by card catalog. We were originally in the Architecture Hall and it was kind of our orange-crate and apple-box phase (before moving to Gould Hall in 1971),” says Betty Lou Wagner, ’51, retired head librarian of what is now known as the Built Environments Library. It also established a rich tradition of student ink and watercolor renderings. In 2006, more than 1,100 historic images were transferred to the UW Libraries Special Collections.

This rendering shows Gould Hall facing west across 15th Avenue N.E. Due to open this fall, the new Gould Pavilion features three multipurpose galleries, a studio/classroom, 1,000 square feet of new instructional space and an exhibition gallery.

For the past 43 years, Gould Hall has been the physical and philosophical home of the College of Built Environments. Daniel Streissguth, ’48, and Gene Zema, ’50, were part of the original architectural team for the 1971 building. Faculty members Grant Hildebrand, Claus Seligman and Robert Albrecht assisted with the design. Named for Carl F. Gould—architecture’s first department chair—the building contains offices, classrooms and library. The hall was designed with wide walkways and shared open spaces to encourage communication and cooperation between programs.

Gould Hall is undergoing a $1.6 million renovation this year. Reconfiguration of the interior will provide an extra 2,500 square feet of usable space. One welcome addition will be exhibition space to showcase student and faculty work. The galleries will be dedicated to honor distinguished architecture alumni: Jim Olson, ’61; George Suyama, ’67; and husband-and-wife Norman Johnston, ’42, and Jane Hastings, ’52.

“I’m grateful to be acknowledged,” says Suyama, founder of Suyama Peterson Deguchi. “It’s recognition that what we’ve done for the past 45 years is valued and understood by other people.”

Architects throughout the world recognized that the end of World War II inspired a new world view—both philosophically and structurally. Germany’s Bauhaus style reached the U.S. and was adopted by universities across the nation. Hastings and her contemporaries called it “glass-box” modernism. Architectural hallmarks included functionality, unadorned designs, the use of steel and glass and an emphasis on craftsmanship and incorporation of other disciplines. UW reflected this when Urban Design and Planning combined with Architecture to form their own college, signaling a more inclusive, cross-disciplinary approach. “There was an emphasis on modernization across the broader culture after the war,” says Ochsner. “The whole character of things changed, including in architecture.”

The inauspicious street-view of the Fauntleroy residence of George Suyama belies breathtaking brilliance inside. Suyama designed his house utilizing classic Northwest elements. It incorporates itself into the landscape and showcases magnificent views. Minimalist in nature, the 1,800-square-foot home celebrates wood materials and expansive glass walls. Beyond its function as a home, it is a symbol of how the identity of the architecture of the Pacific Northwest and UW architecture was established. The residence received the prestigious 2003 Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects Seattle Chapter.

“Architecture in this area has notoriety in terms of using Northwest materials,” says Suyama. “We capitalize on the Northwest’s soft light and expansive views. One of the biggest things we consider is climate. It’s appropriate to live with a sense of the inside and outside coming together.” According to Ochsner, the Northwest School firmly established itself between 1945 and 1975. In some aspects, it became a regional interpretation of modernism and the Bauhaus movement due to its minimalist approach. In 1960, the college’s scope further evolved with the founding of the Landscape Architecture and Building Construction (now Construction Management) departments.

The Neighborhood Design/Build Studio run by Steve Badanes and Chad Robertson created the Danny Woo Community Gardens: Garden Gathering Place in Seattle’s International District.Steve Badanes

“The Northwest School had a very strong reputation in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s,” says Miller. “Characteristics include wood construction, repetition of columns and beams throughout the primary structure, transparency in the building by using glass, generally smaller structures—one or two stories—and often with a courtyard and overhangs.”

Some of the Northwest School’s characteristics sprang from necessity. Hastings and her 1950s contemporaries often employed wood and shingle materials because they were not only inexpensive but also attractive and readily available resources. “We discovered the best buys because we were often working on tight budgets for people of modest means,” recalls Hastings. “That wasn’t true for architects in other areas, but it actually turned out to be to our advantage because we created new styles.”

Over time, sustainability also became a valued Northwest quality. The 1960s saw an increased awareness of environmentalism, a movement that came to be called the “Green Imperative.” The energy crisis of the 1970s further raised awareness of how structures influence and interact with their surroundings.

“Things really got going in the 1980s and the UW was doing some groundbreaking work nationally,” says Miller. That continues today. “The Integrated Design Lab (a 10,000-square-foot facility that partners with local and regional utilities) works on more efficient lighting for buildings. We are also working on using more passive technologies to reduce energy consumption: natural ventilation, day lighting and solar tech.

The Northwest School is now an established approach. Books have been written, classes are taught and awards won. The root, however, may still reside more with individual character than classroom education. “The first people who built here were frequently loggers and fishermen. They knew the right tools and materials to use when building their own homes. It’s kind of natural that the spirit of our area keeps progressing on its own,” says Hastings.

***

For 88 years, Suzzallo Library is awakened every morning by the sun tiptoeing up its facade and illuminating the 36-foot-high stained-glass windows. In contrast, Suzzallo’s modern, front landscape—the bricks of Red Square—shine brightest during rainy days. Laid in 1969, their color burnishes into a fiery hue. Regardless of age, season, fashion or department, the heritage of UW architecture shows a common purpose—serving the community. It strives to reinforce connections between the department and the regional, national and international academic communities.

“At our centennial, we contemplate our legacy and how to continue moving forward with a sense of continuity between past and present,” says Merlino. “Understanding where we’ve been helps determine where we want to go in the future.”

The Master Architect studios are a hallmark of the department’s design curriculum. Pritzker Prize winner Glenn Murcutt and several leading Scandinavian architects have taught studios over the past five years. The college is a leader in historic preservation as well as innovation. Victor Steinbrueck, ’35, a longtime UW architecture professor, was a renowned advocate for safeguarding Seattle character and landmarks such as Pike Place Market against destructive development. “I think it’s fair to say there has been a strong history component for a long time,” says Grant Hildebrand, UW professor emeritus of architecture and art history. “We invented a course called Architectural Utility that was unique among architecture schools. It brought into the curriculum things that history had forgotten, such as low-income housing projects.”

Contemporary programs, such as the Neighborhood Design/Build Studio, put such knowledge into action. The Design/Build program gathers teams of undergraduate and graduate students during spring quarter to collaborate on projects for communities in need. They have created everything from playgrounds to picnic areas for Seattle nonprofit groups. Budgets range from $7,000-$20,000, with money from fundraising, City of Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods and the Howard S. Wright Endowment. “I love this program because it’s a mix of dreamers and pragmatists,” says Steve Badanes, director of the Neighborhood Design/Build Studio and holder of the Howard S. Wright Endowed Chair. “It’s an exciting approach for students to take responsibility for the entire architectural design and building process. Students learn that architecture can make a huge difference in the lives of people who can’t afford it. These projects wouldn’t happen if we weren’t there to do them. My goal is to make students a different kind of architect and show them alternatives to a traditional career.”

Badanes understands the combined power of creativity and construction. He led the group of UW students responsible for creating the Fremont Troll. Public art proposals were put to a public vote and the troll overwhelmingly won. Larger than life, the Seattle favorite officially occupied his home under the Aurora Bridge in December 1990.

“I looked at the site and immediately thought of the old Billy Goats Gruff story. The students and I went to the library and started collecting pictures of trolls,” says Badanes. “The Troll became an icon. It’s wonderful to build something that makes so many people happy.”

Students get their hands dirty as they construct a Design/Build Studio project, the Wellspring

Family Services Playhouse, which came to life to serve kids in Seattle’s Rainier Valley.Steve Badanes

Badanes also co-founded the Mexico Design/Build program in 1995. For a decade, he and students worked south of the border on projects such as schools, clinics and libraries. “What’s amazing is that most of our students tend to stay in the area after graduating,” says Badanes. “Design/Build is an incredibly exciting way to contribute to the local ecosystem. It shows that community-type work can be rewarding. You’re really using your skills for what you should be doing—helping others.”

Traveling abroad has also been a hallmark of UW architecture education. While many students have traveled to Scandinavia, India, Japan, Denmark, Australia and other countries, it’s the Architecture in Rome program that is the most well-known and long-running opportunity for students to see the world from a different perspective. Graduate and undergraduate students study fall quarter at the UW Rome Center based in the 17th century Palazzo Pio. “It’s important for students to interact with a city that has so much history and tradition,” says Trina Deines, associate professor emeritus and former program director. “They learn that the idea of a city is a sacred institution and something to treasure and guard.”

Architecture Professor Astra Zarina founded the program in 1970. On average, 25-30 students participate every fall quarter and interact with the city through drawing, painting and exploration. They also conduct Urban Design Analyses, whereby they observe an area and how people interact with the environment, buildings and each other.

“Studying abroad is an important opportunity. Students learn that human beings have remarkable similarities no matter where they’re from. It strengthens them, gives confidence and helps them be stronger participants in their professional lives,” says Deines.

One of the best ways UW architecture students learn their craft and theory is by participating in the Furniture Studio. Using modern-day applications, students learn how to preserve traditions by designing and fabricating their own, heirloom-quality pieces. Andy Vanags, senior lecturer emeritus, founded the program in 1988. The old-school craftsmanship has won the program more than 50 awards.

“Very few architecture schools teach furniture in a serious way,” says Ochsner, who authored Furniture Studio: Materials Craft, and Architecture. “The influence is significant on making students consider what goes into making something and how materials are used and put together.”

Miller is impressed that current students express interest and passion for design—for addressing “grand challenges” such as sustainability and serving underprivileged groups. They walk through the door ready to find answers.

“Moving into the future, we need to be active players and advocates for a more just and equitable society. We have to be evermore conscious to help architecture play a leadership role in making the world a better place,” says Miller. “The UW has a tremendous reputation and it’s an honor and privilege to be part of the legacy.”

Other College of Built Environments milestones

50 Years | Construction Management

Mercer Court Apartments under construction. The facility opened in 2013 and houses students near the University Bridge in the UW southwest campus. Architect: Ankrom Moisan Architects.Joshua Polansky

The Department of Construction Management celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2014. The program teaches students the managerial and technical skills needed to determine the budget, resources and labor required for successful projects ranging from buildings to bridges, roads to utility plants.

“The program is unique because there has been a very strong connection with local industry since its inception,” says John Schaufelberger, dean of the College of Built Environments and former chair of Construction Management. For example, the Industry Advisory Council was established in 1991 and comprises 30 private-sector representatives who provide input. Students are required to complete 60-day paid internships and some have included working on UW projects such as the Husky Union Building remodel. About a third continue working for the same company after finishing the internship.

In 2010, the department opened a 28,000-square-foot education facility in Sand Point. It provides space for hands-on learning through a virtual construction laboratory, areas for frame construction, classroom space, a library and more. “Over 50 years, I estimate that close to 60 percent of our graduates have ended up working in the Northwest,” says Schaufelberger. “The local landscape would look quite different without the UW Construction Management program.”

20 Years | Community, Environment & Planning

CEP students learn how to be leaders and planners in local and global communities.An Huynh

Community, Environment and Planning (CEP) welcomed its first students in 1994 and is celebrating its 20th anniversary by continuing to offer groundbreaking education based on the principles of planning. CEP is unique among undergraduate majors in that it is self-directed, diverse, and intensely focused on holistic growth through a collaborative process of experiential and interdisciplinary learning. Students develop skills, techniques, and knowledge necessary to be active leaders and conscientious planners in local and global communities.

“CEP has gained distinction as a model for a highly personalized, collaborative, and active educational experience within a large research institution—a CEP education is fully lived, not passively taken,” says Dennis Ryan, founder and past director of the CEP program. The faculty, staff, and students believe that professional practice, personal formation, intentionality, communal learning and stewardship, the core values of the program, are necessary to confront the grand challenges of the 21st century.

While housed in the Department of Urban Design and Planning, CEP encourages active engagement from all areas of knowledge and thus CEP students come from varied disciplines and draw upon the entire range of courses, faculty, and programs at the UW. As part of the program, all students create individualized study plans and complete a senior capstone project. Capstone projects give students a chance to dig deep into a topic they are passionate about. They combine students’ interests and creativity with academic inquiry and professional practice. Recent examples have included the mathematical modeling of Ultimate Frisbee scoring, applying Dutch principles of bicycle infrastructure to Seattle streets, and creating new forms of K-12 education based on permaculture principles.

CEP students seek out and take full advantage of the interdisciplinary nature of the program and their work demonstrates it. “Our students are quite idealistic,” says Christopher Campbell, chair of the Urban Design and Planning Department and director of the CEP Program. “When they leave, they’re ready to build partnerships and imagine solutions that make the world a better place. I can’t wait to see what the next 20 years will bring for CEP and its students.”