You might liken it to a Hollywood tale, complete with heroes, villains, sudden plot twists and a happy ending. With all the hardships and detours along the way, our story might even deserve the title of a summer blockbuster—Mission: Impossible. But after 10 years in the making, the final reel is ready to run, and on Sept. 25 the doors will open at the permanent site of the University of Washington Bothell.

The setting for this epic is a sylvan hillside on one of the last undeveloped pieces of property in the “high-tech corridor” northeast of Seattle. A set designer couldn’t ask for a more dramatic locale: Douglas fir trees tower 100 feet into the air on a ridge overlooking one of the most ambitious wetlands restoration projects in the Pacific Northwest.

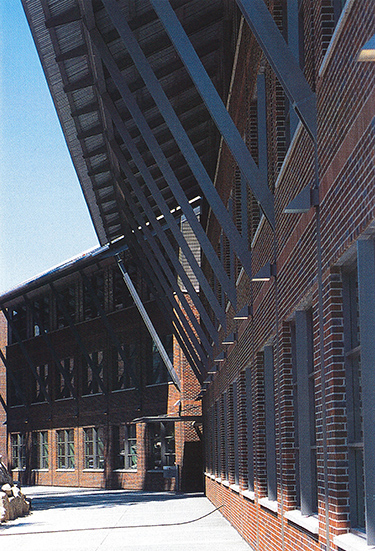

Among these century-old trees, three buildings nestle into the hillside, clad in a rich brown brick that blends with the natural setting. Each structure has a dramatic sloping roof that juts beyond the edge of the building, creating an overhang supported by steel struts—a deliberate reference to the massive timbered lodges found among the lakes and mountains of the Pacific Northwest.

The southernmost building serves the nearly 1,500 juniors, seniors and graduate students who attend UW Bothell to get degrees in liberal studies, nursing, business, computer software and education. To the north is the home of a brand-new institution, Cascadia Community College (CCC), which offers innovative courses for freshmen and sophomores leading to an A.A. degree as well as technical and vocational programs. Between the two is a shared facility that houses the library, media center and student services.

“I love this plan. It's incredible. It's dynamic. The whole look gives me a sense of freedom and creativity.”

UWB Chancellor Warren Buck

“I love this plan,” says UWB Chancellor Warren Buck. “It’s incredible. It’s dynamic. The whole look gives me a sense of freedom and creativity.”

While the final outcome is getting raves, there were times when opponents of satellite campuses called UW Bothell a flop. At one point in its history, a powerful state senator tried to close UWB. Two years later, the governor proposed taking it away from the UW and making it an independent, four-year institution. Even the site was controversial. This was not the place the UW intended to build its third campus, and its original plans never considered sharing a site with a community college.

That UW Bothell finally has a place to call home is the happy ending to a long saga. The problems with UWB’s early years can be summed up with a real estate mantra: “location, location, location.” When the state established five “branch campuses” in 1989 (two for the UW and three for WSU), it set four of them in established cities with a powerful business communities and vocal political support: Tacoma, Vancouver, the Tri-Cities and Spokane.

Then there was the fifth new campus—called UW Bothell/Woodinville—set down provisionally at the end of a business park off the Bothell-Everett Highway. There was no daily newspaper to champion the new campus, no business roundtable to drum up support, and not much interest among the local politicians. “It was clear to me when I took the job that many people right here in the area didn’t know that UW Bothell existed,” says UWB Dean Emeritus Norman Rose, who took over the institution four years after it opened.

Steel struts support the sloping roof of the UWB building in a deliberate reference to the look of resort lodges found in the Pacific Northwest.

When the UW and WSU sold the Legislature on branch campuses, they told lawmakers there was a huge need for upper division and graduate-level courses. While the state’s community colleges did a fine job offering freshman- and sophomore-level classes leading to an A.A. degree, there was a tremendous demand for upper-division courses. These new campuses would help satisfy this need.

But when UWB opened its doors in 1990, there were 143 students when the target was 400. “If there was this huge unmet need, then you’d expect people would be coming out of the woodwork to apply,” grumbled State Sen. Dan McDonald, ’65, ’75.

During the 1991 legislative session, the head of the Senate Higher Education Committee did more than grumble. Sen. Jerry Saling introduced a bill that would have closed UW Bothell permanently. The bill never made it out of committee, but the threat did its damage. “Faculty morale was very, very bad,” says Rose. “Prospective students wondered if there would be a campus to go to in the fall.”

By the fall of 1992, enrollment grew to 439, but that was still 33 percent below that year’s target. Then came another blow to UWB’s stability. At his last press conference before leaving office, Gov. Booth Gardner, ’58, proposed the creation of Cascade State University, turning UW Bothell into a four-year institution with its own board of trustees. The idea came as a complete surprise to lawmakers and the state’s higher education planning agency.

While Gardner’s plan had little political support, more damage was done. “Phone lines are flooded with calls from students asking if they will be able to complete their degrees, wondering about registration, or even withdrawing their applications for admission,” then UW Provost Laurel Wilkening declared.

If Saling and Gardner are the “bad guys” in this saga, Rose is one of the heroes. A longtime UW chemistry professor, Rose had won a Distinguished Teaching Award and chaired the Faculty Senate before taking over UWB in 1994. Once on board, he tirelessly recruited new students and top faculty while trumpeting the strengths of his campus to any and all community groups.

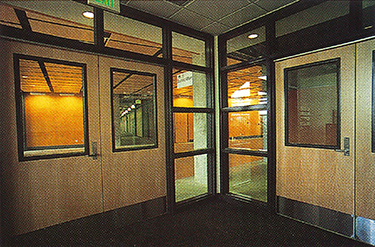

Blonde wood paneling is found in the main reception areas of the campus. Yellow plaster decorates the walls of UWB while blue plaster is the color for CCC.

He and other UW officials convinced the Legislature to add other degree programs to the original liberal studies B.A. By 1998 Bothell was offering degrees in nursing, business, education and computer software. “Bothell looked more like a multiple service university,” Rose explains.

Enrollment started growing by 14 percent each year. Instead of being the “branch” campus that missed its targets, it became the campus with the best enrollment record. “We moved from worst to first,” Rose says. The dean emeritus says many others deserve credit for the turnaround. “The faculty and staff worked very hard,” he says. UWB alumni were also crucial in spreading the word.

Today, even in its temporary quarters, UW Bothell is thriving, with more than 2,500 alumni and 49 faculty. While some students are returning adults who need to complete their college degrees, others are transfers from the community college system or even the Seattle campus. “Our students are so proud and happy to be at the UW Bothell campus,” says Chancellor Buck. “Our class sizes are not huge. Our faculty are very, very good teachers. When students graduate, they tell me they got just as good an education here as anywhere else.”

But while Rose and others were building the academic programs in the ’90s, UWB still didn’t have a place to call home. Originally the UW proposed building its own campus on the site of a golf course north of Woodinville. But Snohomish County officials wouldn’t allow major development on the site, and in the meantime state planners decided a new community college was needed in the area.

Rather than build two separate campuses, the Legislature chose “co-location.” UWB and a new community college would share one site and common facilities, such as student services, a library and parking. The state also decided to buy property at the intersection of I-405 and State Route 522, the Truly Farm, for the new campus, even though some of the property could never be developed due to wetlands.

“It is a really unique site. We will have a fairly large patch of restored habitat in the midst of an urban setting.”

Lyndon Lee, wetlands ecologist

Some UW administrators were not thrilled with the Truly Farm site. They knew that getting permits to develop the property would depend on wetlands approval from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The property had long been on the market—there was even a proposal for a shopping mall, but the wetlands scared developers away. One regent complained that the site was “half swamp.”

The UWB chancellor bristles at the description. “It is an asset as opposed to a liability,” says Buck. “The irony—and this is as good as irony gets—is that the ‘swamp’ is going to be a marvelous, marvelous site for study,” adds Rose. About half of the total campus, 58 acres, is set aside to become a restored wetland.

Someday giant trees will stand over a meandering stream—North Creek—in a setting reminiscent of the landscape prior to European settlement. Taking land that has been logged, drained, grazed and farmed and turning it back into a riverine setting will cost $7.2 million.

“It is impossible to re-create what was there 100 years ago,” says Lyndon Lee, ’83, a wetlands ecologist who oversees the restoration. The project will reconnect the creek to its original flood plain, establish a mosaic of native plant communities and become an attractive place for salmon, birds, beavers, raccoons and maybe even the occasional black bear.

“This is a big deal,” says Lee. “It is a really unique site. We will have a fairly large patch of restored habitat in the midst of an urban setting.” Technically, the state did not have to set aside this much space. By moving beyond what the law required, “the state not only did what they had to do, but it took the next step.”

Buck and Rose say someday scientists from around the nation and the world will come to study the wetlands as they now travel to the UW’s Friday Harbor Research Station in the San Juan Islands. “It is going to be a UW laboratory for the whole system,” says Buck. Already the UW has awarded a $365,000 Tools for Transformation grant to faculty at all three UW campuses to study ecological restoration at the site and at wetlands close to the Seattle and Tacoma campuses.

And while some regents and administrators had problems with the site, the architect who designed the campus, Rick Zieve of NBBJ, says it is a great place for a college. “A site without a challenge is a site not worth building on,” he declares.

He is thrilled that the farm owners never cut down the 100-foot fir trees that cover the hillside. “The size of the trees makes the buildings feel like they’ve been there a long time,” he explains.

Built at another time on another site, the UWB/CCC campus would have looked like an office park surrounded by an ocean of cars. But planners insisted on a pedestrian friendly campus with accessible buildings of a modest scale.

So this first phase of the UWB/CCC campus is organized along a wide pedestrian ‘promenade’ that parallels the contour of the ridge overlooking North Creek. Not only does this walkway provide a natural orientation, it also allows disabled student access to all buildings at the same level.

The three buildings hug the hillside, so that what would be four- or five-story structures on flat land appear from one side to be three-story units. “We didn’t want buildings that were oppressive,” says Zieve.

The shape and materials of the three buildings changed dramatically during the course of the planning. An earlier firm had proposed flat roof structures with metal siding. Chancellor Buck dismissed this as “a Quonset hut look” and Zieve agrees. “It looked like a commercial office park,” he says.

After comments from several focus groups of UWB and community college faculty, NBBJ took a different approach. “They felt it should have the richness, quality and character of the main campus,” says Zieve. He borrowed two basic elements from classic UW buildings such as Suzzallo Library and the Quad: bricks and a sloping roofline.

While the body of these buildings is poured-in-place concrete, they are covered with a brick skin. “Masonry throughout history has signified solidity and dignity, especially compared to metal siding,” notes Zieve.

The sloping roofs inspired Zieve’s team to arrive at an overall design concept for the campus, what they are calling “academic lodge.” Since the hillside was covered with trees, and the design called for sloping roofs, why not borrow elements from a classic Pacific Northwest lodge made of wood timbers?

“We took the notion of a large, expansive roof with an expressed structure holding it up. In our case, it isn’t wood beams but steel struts that are holding it up,” Zieve explains. “The result is a lot of visual interest and texture.” The overhanging roof also has a practical function: it protects part of the outdoor promenade from the region’s rainy weather.

Many lodges have front rooms with large windows overlooking a natural feature. The new campus also borrows this concept with its library reading room, a glass-enclosed space that juts out of its building and overlooks the wetlands. At night freeway drivers will see it lit up, a symbolic beacon of learning for busy Eastside commuters.

So far, the design has gotten raves from those who will live in it. “All that reading room needs is a hearth and a fireplace. Up there, you feel connected to the cosmos,” says Buck.

“I think they got it right,” adds Rose, “Not only the style, but the way they laid out the beginning of the campus.”

Inside, each building is fully wired for current and future technologies. The CCC building has a special distance learning classroom with interactive video technology that is jointly used by both programs. The UWB building includes general classrooms and faculty offices as well as specialty labs for its master’s in management and its bachelor of science in computer and software systems.

Space shared by both programs includes the library, media center, student services areas and science labs. Brian Hall, an associate in one of NBBJ’s planning studios, estimates that the state saved 10 to 15 percent in construction costs by locating the two institutions on one site. It will also see savings in reduced operating expenses. “You start to see some economy because of the scale—parking, for example,” he says.

While not as expensive as the Seattle campus, UWB and CCC students will have to pay for parking. While the parking garages are large, they also have wire mesh screens covering their concrete. In a few years they will be covered with green vines, blending into the surroundings.

Transportation alternatives are encouraged. There will be frequent bus service and the Burke Gilman Bicycle Trail is being extended from its current terminus in Bothell to the campus.

Zieve says that UWB students will come to have as much feeling for their campus as other Huskies have for the Seattle campus. “When we first toured the site, we realized how lucky we were to be building at this place. You could see it was special.

“What we want to see is that emotional attachment. It has the potential to be a place that people really love,” says the architect.

For Rose, it completes the plan the state launched 11 years ago to serve the demand for higher education. “It is the final branch campus to find a permanent home. This is of enormous significance. It is the culmination of an effort that the Legislature began in 1989,” he says.

For Buck it is the next big step for his campus. “It will help us become even stronger in the near future, enhancing our community support,” he says. Ten years from now, he sees a fully developed campus with 8,000 UWB students. “We’ll have a performing arts center and maybe a light rail line coming to campus,” he suggests.

Buck’s vision gets even stronger for the next 100 years. “UCLA started out as a branch campus of Berkeley,” he likes to say. “One hundred years from now, we’ll have Ph.D. programs, our own big time sports teams and maybe even a branch campus on the moon.”

UW Bothell facts

Founded: Oct. 1, 1990

Projected Fall 2000 Enrollment: 1,485

Academic Offerings: Junior- and senior-level classes leading to a bachelor’s degree in liberal studies, business administration, nursing, and computer and software systems. Master’s degrees in education and management. Teacher certification for K-8 levels.

Student Demographics: About 60 percent are 26 and older, 78 percent are working more than 20 hours per week; about half are taking 12 or more credits; 63 percent are from King County and 35 percent from Snohomish County; 37 percent receive some form of financial aid.

Alumni: 2,500 represented by the UW Alumni Association

Campus: 127 acres (58 acres are a wetlands laboratory); cost of land: $22 million; Phases One and Two construction cost $197 million to build 411,000 gross square feet and two parking garages. Completion dates: Phase One, September 2000. Phase Two, September 2001