Last fall Beth and Brian Knudsen traveled to the South Pacific's Marshall Islands to adopt three boys, but there were many things they didn't know.

They didn’t know that the boys were brothers, or that their birth family included six older children. They didn’t know the boys’ exact ages. They didn’t know how the first meeting with the children’s birth family would go. And they certainly didn’t know the complete status of their health.

The information from the adoption agency that referred the three boys to the Knudsens was sketchy-just the boys’ ages (which turned out to be incorrect), some growth measurements and a letter saying they were in “good health.”

Before becoming an instant family, the Knudsens wanted to know as much as possible about these children. They turned to Dr. Julie Bledsoe, a pediatrician who runs the Center for Adoption Medicine, a clinic at the UW Medical Center-Roosevelt. She is the first pediatrician in the Northwest-one of only a few dozen across the United States-specializing in international adoption medicine. Using information provided by orphanages and adoption agencies-which might include medical records, birth histories, photos or videotapes-she tries to determine the health status of children for prospective parents.

“Every country is different in terms of the amount of medical information available and the kinds of health problems children may be at risk for,” Bledsoe says. Currently, most of Bledsoe’s patients are from China, the former Soviet Union and, increasingly, Cambodia.

“I didn’t know much about what problems were prevalent in the Marshall Islands,” Bledsoe says. “I told the Knudsens about common conditions and gave them some prescriptions and my standard talk on risks.”

“She always has good advice, not only medical, but in general. She understands what it's like.”

Beth Knudsen

For the trip to pick up their new sons, the Knudsens packed a barrage of medical supplies: prescription antibiotics in powder form, over-the-counter pain relievers, bandages and thermometers. If needed, they could begin treating minor conditions right away, per instructions from Bledsoe.

When the Knudsens arrived in the tropics, the boys-Brenny, 7; Peter, 4; and Mike, 22 months-did appear to be in relatively good health. Mike had an ear infection, which they treated with an antibiotic, and Peter had a skin rash, to which they applied a cream. Both cleared up quickly.

The other medicines they had brought along, for pink eye, parasites, scabies, diaper rash, lice, dehydration, fever and assorted ailments, were not needed, so the Knudsens left them behind with the adoption agency.

On the family’s return to Seattle, Bledsoe gave each of the boys a thorough checkup, including blood tests. She discovered that all three has been exposed to a the hepatitis B virus and while the older two are free and clear, the youngest needed some medical treatment.

While the virus was a concern, the three Knudsen brothers are doing well and adjusting to their new home. “They’re small for their ages,” Beth Knudsen comments, “but they’ve already grown a lot.” Brenny, who was enrolled in first grade soon after arriving here, grew 2 inches in his first three months in the United States, and Peter grew an inch and a half.

“Julie has just been fantastic,” Knudsen adds. “She’s familiar with Third World conditions and she knew just what we needed.” Bledsoe’s gentle bedside manner was a big help, too, since the children were not used to doctors.

“She always has good advice, not only medical, but in general. She understands what it’s like,” Knudsen says.

Bledsoe and her husband, Dr. Brian Johnston, who is also a pediatrician, adopted an infant Korean boy, Sean, now 2 1/2. They know firsthand what adoptive parents experience, as is often the case with pediatricians specializing in this type of medicine. “We call ourselves ‘owner-operators,’ ” Bledsoe says.

The Knudsen and the Johnston-Bledsoe families are part of a burgeoning trend toward international adoption in this country. It began in the 1960s, when American families began to adopt Korean and Amer-Asian orphans. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, several factors contributed to a dramatic boom in the numbers of children adopted from other countries:

- The number of babies available for adoption in the United States declined to very low numbers.

- Americans learned of the plight of thousands of abandoned orphans in Romania after the fall of Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989.

- Similarly, in the last decade, Americans became more aware of China’s “one-child policy,” which has resulted in girl babies being abandoned in alarming numbers.

- The advent of the Internet has made it easier to find information about international adoption, read personal stories and talk with people who have already had the experience.

The numbers tell the tale: U.S. State Department records show that in 1991, just 62 Chinese children were adopted by American families and brought to the United States. Last year, there were 4,206 Chinese adoptees. During the same seven-year period, the number of international children adopted by Americans almost doubled, from 9,050 to 15,774.

The current crisis in Kosovo has prompted hundreds of calls to the state department about the possibility of adopting war orphans, according to the Associated Press. But authorities discourage adoptions-at least for the next few months. “It’s too early to tell if the children are truly orphans or are just temporarily separated from their families,” U.N. refugee spokeswoman Jennifer Dean told AP. “We do not advocate for international adoption of refugee kids, but rather to reunite them with relatives so that they are in a safe, familiar environment.”

International adoption is complex, expensive and different in each country of origin. The process can cost up to $30,000 and consume as much as three years. The confusion and paperwork vary from country to country. And the U.S. medical community is just beginning to recognize that there is a gap between most pediatricians’ knowledge and the needs of these families.

Some of the early work in this area came out of the International Adoption Clinic at the University of Minnesota. In 1991 researchers there called for internationally adopted children to be routinely screened for hepatitis, tuberculosis, parasites, cytomegalovirus, HIV, retarded growth, hearing and vision problems and other medical conditions. Screening for these conditions was not common practice at the time.

The Minnesota researchers tested 293 children adopted from overseas and found that 57 percent had at least one “important medical condition.” Of these maladies, 81 percent were “silent diseases” not found by physical examinations, but by simple, non-invasive screening tests. Infectious diseases made up the majority (73 percent) of the conditions. More than a third of the medical problems could be corrected, the report concluded, and a failure to detect them might have entailed long-term consequences for the child or other family members.

One common silent disease is hepatitis B. Worldwide, it is the most common chronic viral infection, affecting more than 300 million people, according Adoption Medical News, a newsletter for physicians practicing international adoption medicine. The virus is a major cause of death in regions where it is endemic. Over a lifetime, about one-third of chronically infected people die from hepatitis B or one of its complications, which include progressive liver disease, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The highest rates of infection are in Asia and Eastern Europe, especially Romania.

Tests for hepatitis B done in a child’s country of origin are highly unreliable, the newsletter states. Results are often false or confusing. To further complicate the issue, testing done outside the United States might actually cause children to be exposed to the virus or other blood-borne infections, such as HIV, because needles are often reused.

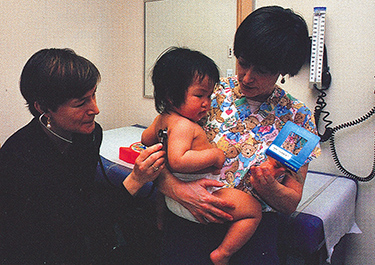

Adoption medicine specialist Dr. Julie Bledsoe (left) examines little Paige Lockridge as her mother, Terrie, looks on. Photo by Mary Levin.

Although detecting medical problems after the adoption is imperative, most of Bledsoe’s work, and the trickiest part, occurs before parents ever meet their adopted children. Each week Bledsoe reviews between 10 and 20 sets of records for prospective parents. Since medical standards and procedures vary from country to country, she must interpret medical terminology that the average pediatrician is unfamiliar with.

“You have to take everything on the medical record seriously, but everything is also suspect,” Bledsoe says. In many cases records are missing, inaccurate, or simply false. Often vaccinations have been given incorrectly or ineffectively. Bledsoe does what she can to fit together the available jigsaw pieces into a picture of the child’s health.

The best news is that with experience comes knowledge. “The more we do it, the more we know what to look for,” Bledsoe says. For example, she knows that fetal alcohol syndrome is prevalent in the former Soviet Union and that Chinese orphans may have low dietary iodine and develop hypothyroidism.

If measurements of a child’s height, weight and head circumference over a period of time are provided, pediatricians can plot a growth chart to gauge normal development. A growth chart provides great clues, but you have to know what to look for, Bledsoe explains.

“You should use a growth grid appropriate to the child’s ethnic background,” she explains. Chinese heads, for example, are smaller than Caucasians’. Growth patterns plotted on the wrong chart might seem to indicate problems where none exist. “What I always worry about is a family turning down a child on the basis of incorrect information,” Bledsoe says.

Families looking into adoption are asked if they will consider a child with serious illnesses, such as AIDS or cancer, birth defects, or retarded physical, mental or emotional development. Some parents chose these harder-to-place children, as Bledsoe and Johnston did. Their son, Sean, has a cleft palette, requiring several operations to correct.

And then there’s the reverse situation-when people believe they’re adopting a healthy child only to discover there are unexpected problems.

“People live in constant fear of that,” Bledsoe acknowledges. “I explain very clearly up front that I’m going to do my best job to tell them what I think the health of the child is. But there are certain things that we can’t know because we don’t have that information. We can be wrong either way. I try to prepare people for the worst-case scenarios.”

“Birth isn't risk-free, either. At some point, you just have to take the leap.”

Julie Bledsoe

An important fact for prospective parents to face is that no child comes with a guarantee. “It’s not nice to hear that-but birth isn’t risk-free, either,” remarks Bledsoe. “At some point, you just have to take the leap.”

Even with the built-in uncertainties of adoption, most end happily, Bledsoe says.

“One study, sponsored by the Joint Council on International Children’s Services, interviewed more than 700 families who had adopted internationally through agencies all over the country. The survey found that 90 percent of the parents felt they were with the child they were meant to be with-and that’s all comers, even people whose children have major medical problems,” Bledsoe says. “Those are pretty good statistics. It speaks to the fact that bonding between a parent and child goes beyond an illness.”

University of Minnesota pediatrician Dana Johnson, who founded Minnesota’s adoption medicine clinic, agrees. “All children come with problems. Institutionalized children just come with different ones,” he says. “Most families are happy.”

Johnson and Bledsoe, as well as the handful of other pediatricians, are on the cutting edge of transforming our understanding of international adoption. Bledsoe wants her clinic to be a regional clearinghouse of information for adoptive families. She’s building a network of therapists and specialists who are knowledgeable about adoption, gathering books for a library and introducing adoptive families to each other. Bledsoe says she’s planning educational events, such as asking adult Asian adoptees to talk to adoptive parents about their experiences.

The UW also hosts an e-mail discussion group of about 45 physicians practicing international adoption medicine in the United States and Canada who discuss their findings and share information. The group is trying to work more closely with adoption agencies, Bledsoe says.

“We know we create more work for adoption agencies. Our hope is also to identify factors that improve outcomes for orphanages, such as increasing the ratio of caregivers to children. We’d like to standardize how they take videos. It would be wonderful if we could get a trained person to go through a developmental assessment with a child on videotape.”

In addition to assessing a child’s possible physical problems, parents must also consider issues of attachment and developmental delays. Although conditions vary greatly, living in an orphanage is not the best way to get a child started, experts agree. It’s estimated that for every three months a child is placed in an orphanage, he or she will be delayed one month in development.

Johnson agrees that institutionalization is an important factor in the development of adopted children. “A lot of what we knew, but never fully appreciated, is the effect of kids spending their formative years in institutions, as opposed to being with a family,” he says. “Kids that have been institutionalized need rehabilitation time. Our knowledge of the effects of deprivation and institutionalization is important in making initial decisions on adoption as well as in parenting afterwards. And families are more comfortable making decisions when they have more information, so they’re more likely to adopt.”

Although institutionalization is a concern, it’s not insurmountable. “A lot of children do catch up, and pretty dramatically,” Bledsoe says.

Bledsoe points out that some orphanages are adequate-and they are certainly better than no care at all. “It’s very clear there are some wonderful orphanages,” she says. Although there have been no scientific studies yet, Bledsoe has encouraging anecdotal evidence. “In Cambodia, for example, the orphanage setting is physically poor, but every child is with one caregiver, so their attachment issues, their bonding issues and their developmental issues are much less a concern,” she says.

One of Bledsoe’s patient-families appreciates the good start their children received in Chinese orphanages, or “social welfare homes,” as they are called in China.

Sally Yamasaki and her husband, Dan Benson, adopted two Chinese daughters, the first in 1994 and the second in 1998. “We have lots of friends in China and travel there often,” Yamasaki says. “We’re familiar with the culture and the country. That led us to want to adopt from China.”

Both daughters, Lina, 4, and Lara, 1, seem to have been well-cared for. Yamasaki and Benson were even able to visit the social welfare home that Lina came from. “It was a nice place,” Yamasaki says. “There was one child to a crib and 12 to 15 children to a room with four caregivers.” She said there was a playground outside and the home seemed well run.

The couple didn’t have the benefit of adoption medicine when Lina joined the family. Their first experience with this new medical field came with the most recent addition to the family, Lara. “It made a world of difference,” Yamasaki says. What made Bledsoe different from the general pediatrician who took care of their first daughter, Lina, was that Bledsoe is herself an adoptive mother, Yamasaki says.

Yamasaki says the information she and her husband received was comforting. Although they tried to read as much as possible, they could never keep up with all that Bledsoe knows. “She’s familiar with the medical situation in other countries and knows how to interpret a typical medical report.”

When they traveled to China last year to pick up Lara, they were not allowed to visit the social welfare home where she had been living and weren’t able to acquire much information. But Lara’s health was good (she had only a case of dermatitis), she is developmentally advanced and shows no physical delays.

“As time goes on, we just appreciate Julie more. She has a complete understanding of the concerns we have as adoptive parents,” Yamasaki comments.

Besides the physical health issues, Yamasaki says, emotional aspects are also nurtured in a clinic like this. Taking good physical care of a child is one thing; what’s more difficult in parenting is providing for a child’s emotional well-being. “You want to do the right thing,” she says.

Yamasaki is thinking ahead. “When the girls reach puberty and begin their search for identity, I can help them from the aspect of being an Asian American,” she says. “But I’m going to be grateful that they’ll also be able to talk with Julie.”

Yamasaki adds a personal thought. “People who haven’t adopted always think the child is lucky. But we’re all lucky,” she says. “We feel fortunate to be a family.”