Where musical minds met Where musical minds met UW had a big role in sparking the ‘Seattle sound’

In the 1980s, the UW brought together many of the individuals who would go on to music stardom.

In the 1980s, the UW brought together many of the individuals who would go on to music stardom.

Four weeks into the fall semester of 1975, the third floor of the north wing of McCarty Hall virtually shut down one afternoon. That was the day Patti Smith's album Horses came out and, along with about 10 of my friends, I cut class and listened to this tremendous record so many times that the vinyl finally wore out. This was back in the days when wax ruled, and by the sixtieth spin of the day, little bits of vinyl had come off the album and were wound around the stylus. At midnight, the R.A. (the dreaded floor Residence Advisor) finally stopped by to tell us to shut off what was now just distorted noise blasting forth from my tiny Electrophonic stereo.

Though my McCarty Hall antics wasn’t the first time loud, obnoxious rock ‘n’ roll blasted out on the University of Washington campus, by the time the late ’80s rolled around a decidedly different music began to spew forth from dorms and frat houses. It had elements of punk and garage rock, just like the New York Dolls records I’d used to torture my floormates with, yet it was different—a slower beat and heavier bass.

This particular version of garage punk was a hometown brew created by bands from the Northwest; some of the musicians even went to the UW. Though locals hated the name—since it only described about one-tenth of the local bands at the time—out-of-town critics dubbed it “grunge.” The term stuck, and what was simply a happenstance confluence of many divergent talents became a movement. On local independent labels like Sub Pop and C/Z, it was a sound that first took over the “U” District, the Rainbow Tavern, the HUB Ballroom, and eventually conquered the Wal-Mart.

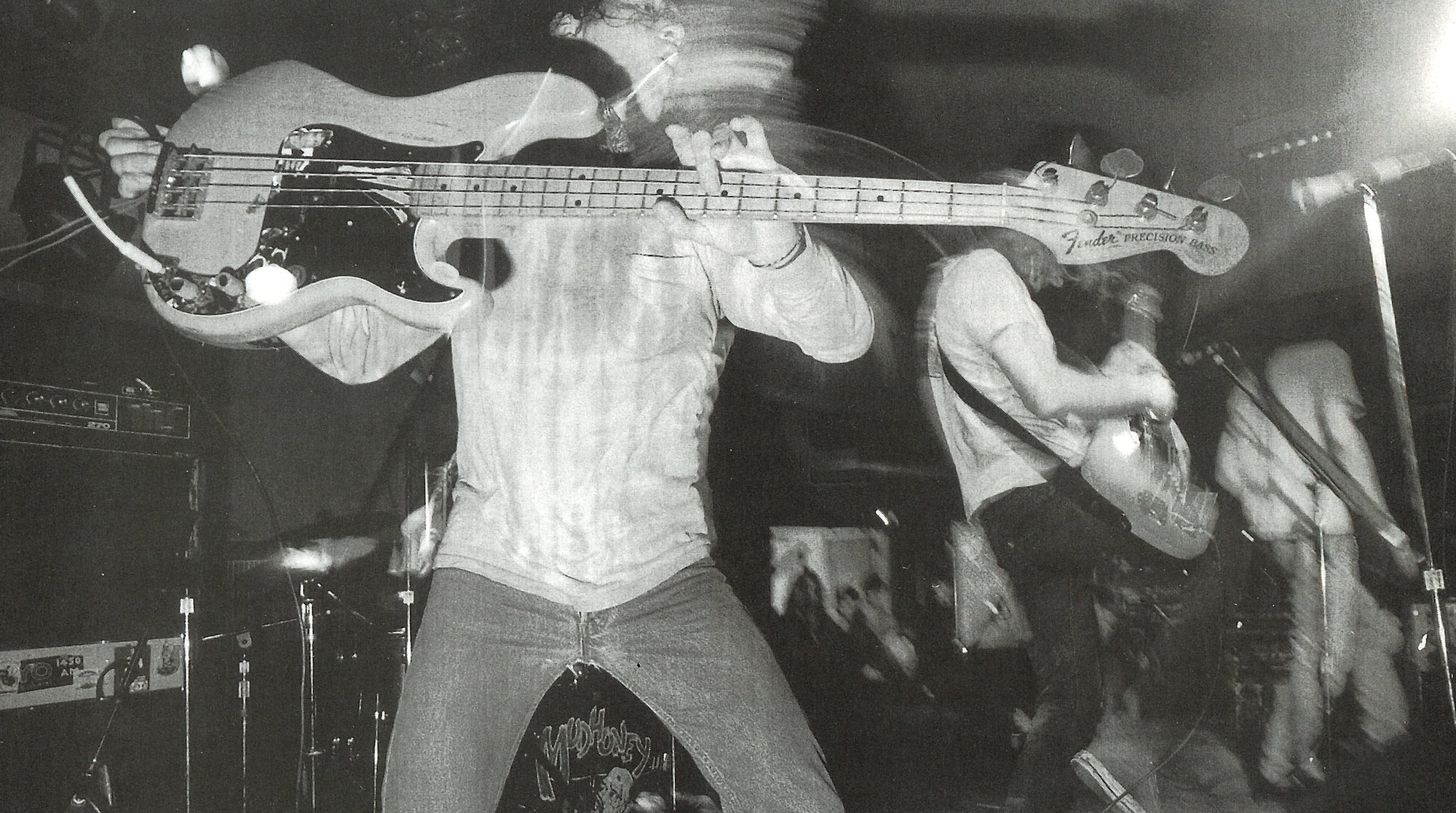

And it even took over Terry Hall. Imagine the chagrin of the Terry/Lander R.A. who had to go tell the kid down the hall to quiet down, but found the offending dorm rat was Mark Arm, already making a name for himself as a troublemaker. Not only did Arm have the nerve to live in the dorms while he attended the UW (at least for a quarter), he went on to front both Green River and Mudhoney (pictured at top), arguably the two most “grunge” bands to ever come out of the Northwest.

Mudhoney. Photo courtesy of Reprise Records.

Charles Peterson, ’87, who himself gained fame and international prominence as the photographer who documented the “grunge” explosion, met Arm when they both lived in Terry Hall. “Mark was in a band called Mr. Epp at the time,” remembers Peterson. “He was totally straight-edge, but he was just as cynical and as smart as ever. I also met Ed Fotheringham (The Thrown-Ups) and Kim Thayil (Soundgarden) around the same time.” There must have been some great parties in Terry back then.

If only because it attracted creative types from around the Northwest who were going to college, the University of Washington ended up as a meeting ground for many of the individuals who would go on to form bands that made an impact. The UW itself didn’t really have much to do with explosion of grunge (during my tenure at least the music department never held a class on “The Appreciation of Sonic Youth”). But it happened to be the Petri dish that served as breeding ground for many of the young, idealistic rockers who populated Seattle in the ’80s. For centuries universities have played this role in society—they are the launching ground for most social and political revolutions, from bra burning to Communism to the counterculture. This time around the ideology was nothing more than a do-it-yourself rock ‘n’ roll attitude with electric guitars turned up as loud they would go.

And no one did it better than Mudhoney, with perhaps at least some of Mark Arm’s angst built up from his time in Terry Hall. But Mudhoney isn’t the only band with ties to the University of Washington. Others include Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, TAD, The Presidents of the United States of America, Mad Season, The Posies, The Screaming Trees, Skinyard, and the list goes on and on.

Though the UW might be known nationally for its research tradition or its football team, almost every major Northwest band of the last decade can be traced to the University of Washington in some form or another, with at least one member attending school at some point (graduating is another matter altogether). And the UW’s role in those who made up the scene but who weren’t musicians—the promoters, radio disc jockeys, journalists or record producers—is even larger, and more significant.

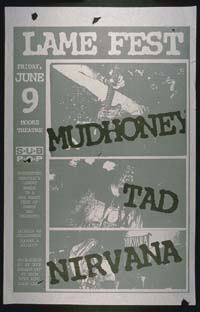

Even the history of Nirvana has a small UW chapter. The band played a show at the HUB Ball-room on Feb. 25, 1989, part of a bill that boasted “Four Bands for a Buck.” It was one of their most infamous local concerts. They not only trashed their instruments, they also destroyed the HUB’s PA system and hence were “banned for life” from the University of Washington, or so said University administrators. Kurt Cobain joked about it in interviews and the line “Banned For Life” ended up as the title of one of their most famous bootleg CDs, recorded at another Seattle show.

Even the history of Nirvana has a small UW chapter. The band played a show at the HUB Ball-room on Feb. 25, 1989, part of a bill that boasted “Four Bands for a Buck.” It was one of their most infamous local concerts. They not only trashed their instruments, they also destroyed the HUB’s PA system and hence were “banned for life” from the University of Washington, or so said University administrators. Kurt Cobain joked about it in interviews and the line “Banned For Life” ended up as the title of one of their most famous bootleg CDs, recorded at another Seattle show.

The UW’s musical roots stretch back far beyond grunge, though, and begin with entertainers like Stan Boreson (class of 1950) and Jimmy Oglivy of Dynamics (1964). Pre-grunge, the biggest band launched from the UW campus was the Brothers Four, who formed at the Phi Gamma Delta frat house and scored a No. 2 hit in 1960 with “Greenfields.” Like Kurt Cobain they wore sweaters, though their sound was decidedly square even in the ’60s.

Also making waves during the ’60s was Larry Coryell, who attended the UW and went on to become one of the most famous jazz guitarists ever, helping to launch the jazz fusion movement. During the psychedelic ’60s, most Seattle bands began at the UW or at least had roots to the student underground movement. The Time Machine, Chrome Syrcus, and the Daily Flash all had connections to the UW and played gigs on or around campus, usually complete with light shows.

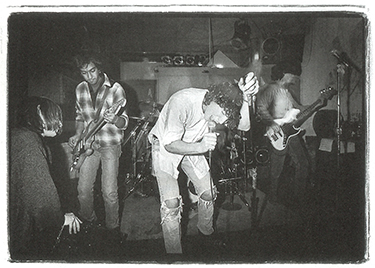

A very young Soundgarden takes the stage at the tiny Ditto Tavern in Belltown in this 1985 photo. UW graduate Kim Thayil, the lead guitarist at the left, has yet to grow his signature beard. Singer Chris Cornell, center, has yet to take off his shirt. Photo © 1985 Charles Peterson.

By the time I began attending the University in 1975 (and working at The Daily), there were only a handful of local bands worth writing about, and most of them were folk or blues. I don’t know if Jim Page ever registered for classes at the UW but I’d say he qualified for an honorary degree considering how many performances he did in Red Square over the years. The Cowboys and The Heats were the big local bands during my undergraduate years, though both had ties to high schools rather than universities.

Kenny Gorelick, ’78, went to the UW during this era. It’s probably safe to say that even including grunge, the saxophonist (who goes by “Kenny G” nowadays) is the most commercially successful musician to ever attend the UW. Gorelick graduated, not as a music major, but with a B.A. in accounting.

What’s thought of as the modern Seattle music scene began in the late ’80s and even Jonathan Poneman—one of the co-founders of Sub Pop records—spent at least some time attending classes at the UW. Poneman, like many of the music fanatics in Seattle at the time, found a welcome home at KCMU, the student-run campus radio station. Also doing a show at KCMU was Bruce Pavitt (who had attended Evergreen State College), and the two formed a partnership that became Sub Pop, the most influential “indie” record label of the last three decades. Many of the bands that went on to sign with Sub Pop were first exposed to Seattle audiences through KCMU.

For several years KCMU was ground central for the Seattle music scene. It was the only area radio station that regularly supported local bands, and, if its listenership was tiny, it was influential in breaking many bands, and not just Seattle bands (KCMU also made the Legendary Pink Dots legendary by repeated airplay). At times the station had more DJs than listeners, but it’s no exaggeration to say that virtually every volunteer who had an air shift in the late ’80s ended up getting a job in the music industry or playing some role in the Seattle scene.

“KCMU helped create a really vibrant and self-aware music scene,” remembers Faith Henschel, ’88, who was music director in the early ’80s. “It gave everyone a sense of community. The time I’m speaking of was before the grunge phenomenon but KCMU was still very sympathetic to local bands.” Henschel has herself gone on to become a vice president of marketing at Capitol Records in Los Angeles.

Soundgarden includes (from left) Matt Cameron, Ben Shepherd, Kim Thayil and Chris Cornell. Photo by Kevin Westenberg, courtesy of A&M Records.

Henschel and KCMU also had a major role in breaking one local band that eventually went on to become one of the biggest successes out of Seattle. Kim Thayil, ’84, and Hiro Yamamoto had moved to Seattle following their high school buddy Bruce Pavitt, who had come to the Northwest to go the school at Evergreen. Thayil wasn’t taken with Evergreen and ended up moving to Seattle to enroll at the UW. It was there that he won a prize on KCMU (listenership was small enough that there wasn’t a lot of competition). “I went down to pick up my prize,” Thayil later told Alternative Press, “and they said, `You’re always around anyway, how’d you like to work here full-time?’ ” Thayil ended up becoming a popular DJ on the station and he also managed to last all four years at the UW—one of the few musicians who finished. He eventually graduated with a degree in philosophy.

Thayil’s band Soundgarden soon linked up with manager Susan Silver (who had also attended classes at the UW) and the group received their first radio exposure came from KCMU. “I re-member the day we got the first Soundgarden single in and how many times we spun that,” recalls Mike Fuller, ’82, another KCMU vet. “KCMU broke that band, at least locally.” Fuller now works as a DJ with Kidstar radio in Seattle.

Thayil’s own show on KCMU is best remembered by other jocks as “eclectic” but it reflected what Henschel describes as “his personal favorites.” It was that ability to go out on a limb—a creativity only allowed at the time on college radio—that helped support a revolutionary new style of music. “When Kim and Bruce [Pavitt] played those sort of records, it helped lead to acceptance of their favorite music and eventually to acceptance of their own bands,” says Henschel.

The list of KCMU volunteers in the late ’80s (most of whom were students) reads like a who’s who of the Seattle music industry in the ’90s. Apart from musicians like Thayil and Yamamoto from Soundgarden, Steve Turner of Mudhoney also contributed, as did Jeff Smith of Mr. Epp, and Scott Vanderpool of Chemistry Set. There were the label mavens like Poneman and Pavitt, plus numerous DJs that eventually tried their hand at journalism: Veronika Kalmar, now man-aging editor of The Rocket; Jeff Gilbert, Guitar World’s Seattle beat reporter; Peter Blecha, now with The Experience Music Project; and Glen Boyd, a journalist and promoter who went on to work at both Nasty-Mix and American Recordings. At the time, the line between being a fan and being a promoter was thin, since both the audience and the stakes seemed so small.

The list of KCMU volunteers in the late ’80s (most of whom were students) reads like a who’s who of the Seattle music industry in the ’90s. Apart from musicians like Thayil and Yamamoto from Soundgarden, Steve Turner of Mudhoney also contributed, as did Jeff Smith of Mr. Epp, and Scott Vanderpool of Chemistry Set. There were the label mavens like Poneman and Pavitt, plus numerous DJs that eventually tried their hand at journalism: Veronika Kalmar, now man-aging editor of The Rocket; Jeff Gilbert, Guitar World’s Seattle beat reporter; Peter Blecha, now with The Experience Music Project; and Glen Boyd, a journalist and promoter who went on to work at both Nasty-Mix and American Recordings. At the time, the line between being a fan and being a promoter was thin, since both the audience and the stakes seemed so small.

As music director, Henschel was part chamber of commerce and part salesperson. She did something few DJs ever do: She started promoting the bands the station was playing to national labels. She put together a tape, prophetically titled “Bands That Will Make Money,” and sent it to everyone she could think of in the music industry both locally and nationally. The tape featured a collection of Seattle bands that weren’t getting attention outside of the area. “She included bands that the station was playing a lot, and that they’d carted up, but that no one else had heard of,” says Dave Rosencrans, ’88, former KCMUer. “And when she sent them out, it garnered a lot of attention.”

Screaming Trees includes (from left) Gary Lee Conner, guitar; former UW student Barrett Martin, drums; Mark Lanegan, vocals; and Van Conner, bass. Photo by Michael Lane, courtesy of Epic Records.

Rosencrans did more than just play Seattle bands on the radio—he also had a job with the ASUW Arts and Entertainment department and was responsible for booking many of the bands that played on campus. During his tenure he was the first local promoter to bring many alternative bands to Seattle including such national luminaries as Billy Bragg, Steve Earle, Game Theory and The Go-Betweens. Rosencrans almost always booked local acts to open these shows and those opening spots were important in the careers of groups like Pure Joy and Chemistry Set.

“Remember these were the Reagan years,” he says, “and not many people were taking chances on underground bands. But because we were a student organization we could take a chance on some more `out there’ bands.”

The job of ASUW concert promoter was almost as important as KCMU in terms of serving as a launching ground for UW students who went on to have careers in the music industry. Rosencrans is now the International Product Manager of Sub Pop, where he promotes some of the bands that he helped get exposure back in college.

Others to hold the A&E job include John Kohl, ’81, and Mark Rose, both of whom graduated from promoting shows at the UW to promoting concerts in the real world. Rose and Kohl both work with major record labels in the high-pressure world of record promotion, but it was experience at the UW that helped them get their start. “I remember walking into the ASUW and saying I wanted to work shows, and they told me I was then the production manager,” says Rose. “I got a little badge. That’s how I got my job when I left the U.”

Kohl remembers his experience at the UW as a chance to experiment in an environment where experimentation was encouraged—a theme echoed by others. “I think the UW brought a lot of creative people into its larger community,” Kohl said. “A lot of people might have come here for the UW, but they stayed and became members of the larger music community.”

The Presidents of the United States of America include (from left) former UW grad student Dave Dederder, Jason Finn and Chris Ballew. Photo by Karen Mason, courtesy of Columbia Records.

Like Rose and Kohl, Mark Gorlick, ’80, started out working behind the scenes in the music in-dustry (in record promotion) while a student at the UW. He’s gone on to make a career of it as a senior vice president of promotions with MCA Records in Los Angeles, perhaps the highest profile job any UW alumnus has within the music industry. “I first worked as a college rep for Columbia Records, and it’s a job I couldn’t have gotten if I wasn’t a student at the UW,” he says. “That opened the doors. I met a lot of people in college radio. I wrote for The Daily. I made connections. Many of those connections I made are with people I still work with 20 years later.”

Gorlick, the local record guy who brought me my first copy of an Elvis Costello album (which changed my life), was at the UW at a time when the local music scene was sleepy compared to the explosion that would occur a decade later. “I shudder to think what it would have been like if all the people I went through school with had been around when the Seattle scene was exploding,” he recalls. “When I went to the UW, the big groups were Heart, Bighorn, Child and Rail. Now we have real bands.”

The emergence of “real” bands also has changed the dynamics of the student rock ‘n’ roller. With so many successful bands in the Northwest in the past decade, more aspiring rockers think of music as an actual career. A decade ago, most of the Seattle scene bands all started off thinking they were going to have day jobs instead of music careers—and education at universities played a role in that. Today, when superstardom seems ordinary, fewer bands in the area seem to have ties to the University because many young musicians expect (sometimes wrongly) that they will be able to make a living from playing music.

Still, as rock ‘n’ roll becomes a real career path, some successful musicians are now starting to think about graduate school. Dave Dederer of The Presidents of the United States went to grad school at the UW, one of the few rockers with such lofty credentials. And drummer Barrett Martin— who has played with some of the biggest groups in the region including Mad Season, Screaming Trees and Skinyard—now says he’d like to go back to the UW for postgraduate study when his music career slows down.

“I’d love to have the time to study anthropology, or sociology, and it seems like it would be a great luxury to have the time spend your life working in that,” he says. Could Eddie Vedder be next, perhaps enrolling to study political science to better handle his fight with Ticketmaster?

The bands that have found the greatest success from the Northwest in the past couple of years no longer reflect such a singular sensibility as grunge, so even though the scene continues, it’s getting less national press. Bands like Foo Fighters, The Presidents of the United States of America, and Everclear represent the second wave of the Northwest scene and they all were played on commercial radio before KCMU.

Yet as time marches on, the history books remind us of a time when you could see Nirvana at the HUB for a buck, when Soundgarden was playing just up the street at the Rainbow Tavern, and when KCMU was the only station worth punching in on your car radio. It was an era of innocence when the measure of success was determined by playing a show at the Scoundrel’s Lair (now a pizza place, across from the Red Robin on Eastlake, and a longtime UW hangout) to 20 of your friends and fellow students.

“I remember back when Bruce Pavitt was doing his Sub Pop radio show for KCMU,” recalls Mike Fuller. “I followed one of his shifts once and when I went in there he was asleep. The record that he’d been playing was stuck with the needle in the center groove and it was going `ka-chung, kachung.’ Bruce was slumped over the control panel snoring. I don’t know how long it had been that way but it could have been hours. And the funny thing was, not a single person had called up the station to complain.”