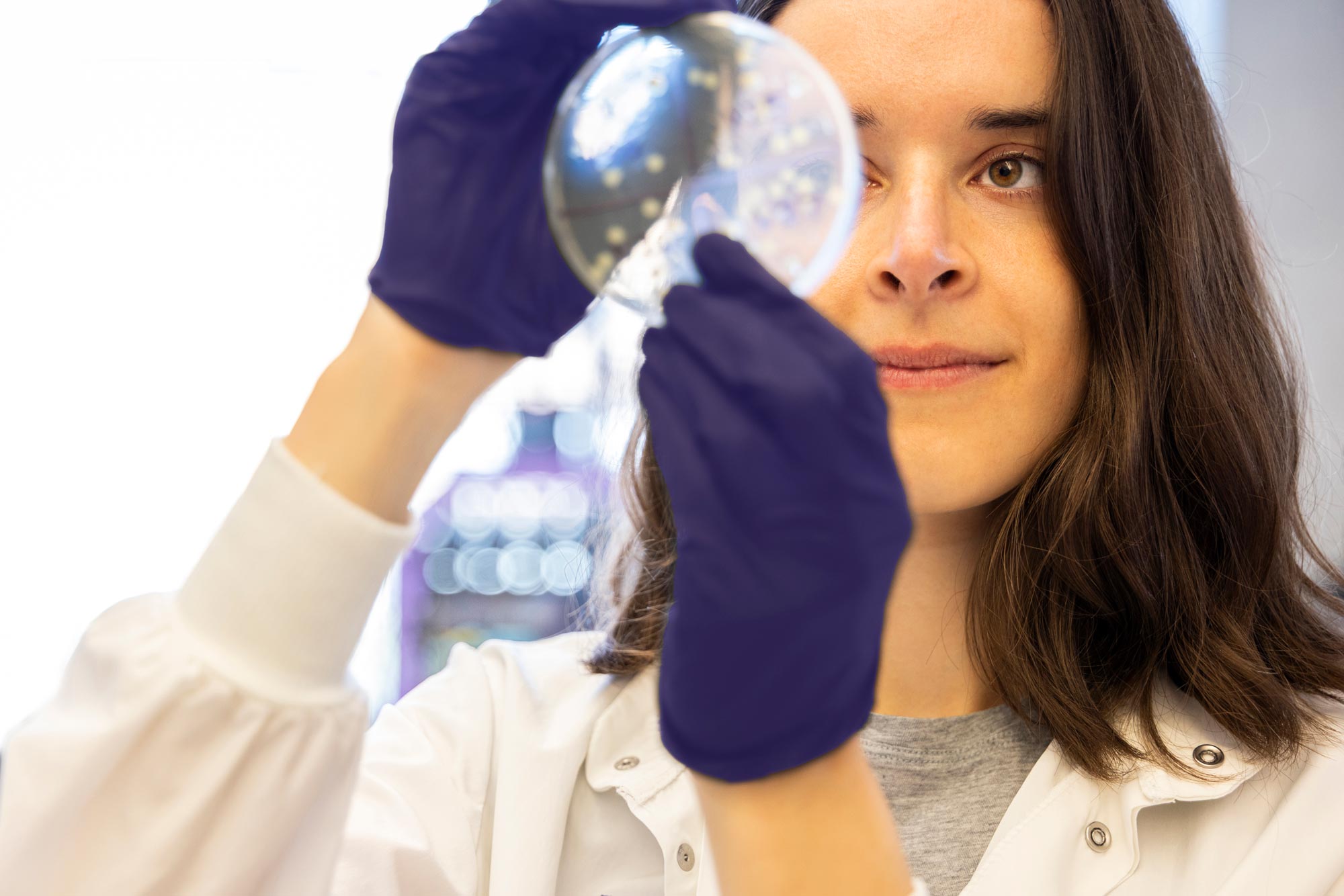

That enormous potential is what attracted Christina Savvides, ’29, to the IPD. She’s working toward a UW medical degree and a doctorate in molecular engineering, thanks in part to the Oren Traub Endowed Fellowship, which supports students enrolled in the UW School of Medicine’s Medical Scientist Training Program.

“I want to be what is called a physician scientist,”says Savvides, who chose the UW for its top-notch program and collaborative research environment. “A core principle is the idea of ‘bench to bedside,’” she explains, referring to a medicine’s journey from being developed in the lab to becoming available to patients. “I want to offer something to patients who have no viable treatment options.” The protein research she’s now working on could be that hope for people with rheumatoid arthritis.

Savvides describes the current treatment options for this painful autoimmune disorder as a “sledgehammer” approach. These medications are not elective for all patients—and for those who do respond, the medicines can cause collateral damage to tissue and organs. Though patients may continue treatment despite the side effects, many are unhappy with their current options. Savvides’ goal is to find the key to target just the immune system “and avoid that destruction.”

The IPD has already successfully created one medicine based on computer-generated proteins: a COVID-19 vaccine authorized in the United Kingdom and South Korea. Other IPD breakthroughs that might save or improve lives include new antivenoms for snakebites, a flu shot you may need only once in your lifetime (currently in clinical testing), antibiotics that combat drug-resistant bacteria, a better vaccine to prevent malaria—the number-one killer of young children worldwide—and more effective cancer treatments.

“One of the challenges in recognizing cancer cells has been they don’t look very different from normal cells,” Baker says. “We’ve recently developed a technology that can measure key markers of cancer proteins. This gives us a whole new way of targeting cancer cells.”

Getting a new medical treatment from a university lab to patients is a complex process, requiring clinical trials and approvals from regulators. Spinout companies play a role by testing and commercializing new medicines so they can get to doctors and the patients who’ll benefit from them. So far, Baker has launched 21 biotech companies, many of them in Seattle—including the single largest new biotech firm in 2024.

And philanthropy remains a crucial piece of the process. “This is a time when people can support absolutely critical research,” Baker says. He notes that, like the visionary philanthropy that opened doors for the IPD’s beginnings, today’s support can push on-the-cusp discoveries forward and transform people’s health and well-being everywhere.

Investing in graduate students keeps discovery moving

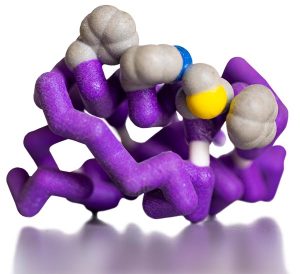

A 3D-printed model of a protein designed using AI-powered tools.

There are UW graduate students like Savvides behind every breakthrough at the Institute for Protein Design—from innovative AI tools to cancer-targeting proteins.

“They drive innovation and discovery in our research group,”says Baker about the IPD’s 92 current doctoral students, who are training to become the future doctors, faculty, researchers and biotech company leaders of America.

For decades, state and federal funding has created a vital pathway for graduate students—but recent cuts are forcing many to walk away from their education and critical research. “It would be an absolute disaster for us and for American science,” Baker notes, “if students cannot continue their education because of funding cuts.”

That’s why the UW is launching a bold, University wide initiative for graduate student support. When you support the Graduate Student Research Resilience Fund, you can make an immediate impact for students like Savvides and the lifesaving work she’s doing at the UW—and keep the discoveries coming.

Learn more about supporting the Graduate Student Research Resilience Fund.