February 2020 might seem a lifetime ago, but that’s when UW Medicine researchers were the first to report community spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States. They knew the discovery had massive implications, even if the general public couldn’t yet fathom them. But what happened next was months, even years, in the making.

Long before the current pandemic arrived, preparation for one was happening behind the scenes—especially in Seattle. Home to cutting-edge hospitals and research engines, the Pacific Northwest is known as a medical powerhouse. Jeff Brotman, ’64, ’67, the late co-founder of Costco, envisioned creating an entity that would unite our region’s research strengths.

Brotman’s friend Dan Baty, ’65, shared that vision. In 2017, thanks to the philanthropic leadership of Jeff and Susan Brotman and Dan and Pam Baty, the Brotman Baty Institute for Precision Medicine (BBI) was launched. It would combine the expertise of UW Medicine, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Seattle Children’s.

Soon after, another local visionary, Bill Gates, stepped up to help the region prepare for the possibility of a pandemic. Fortunately, a few key investigators were already laying the groundwork.

At the Institute for Disease Modeling, principal research scientist Mike Famulare and colleagues suggested a way to monitor the seasonal transmission of respiratory viruses and help prepare for a pandemic. And researcher Trevor Bedford, with the Hutch and Nextstrain, was discussing how to speed up genomic sequencing of pathogens and better map their spread.

The teams eventually joined forces. In 2018, with funding from Gates Ventures (Gates’s private office) and in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and UW Medicine, the BBI launched the Seattle Flu Study.

The new initiative would focus on influenza, in part because many in the field saw respiratory viruses as a likely source of the next pandemic. Sooner than anyone thought, they’d be proved right.

The Seattle Flu Study began to pay off immediately. Researchers discovered that the physical distancing forced by Seattle’s massive snowstorm in early 2019 led to a dip in transmission of nearly all respiratory pathogens.

Soon, a more efficient, convenient approach to testing—“swab-and-send”—was developed by Dr. Helen Chu, assistant professor of medicine in UW Medicine’s Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. When a novel coronavirus emerged in China, the Seattle Flu Study added it to the pathogens the study was testing for.

No one expected what happened next: On Feb. 27 of this year, the Seattle Flu Study team discovered that the novel coronavirus was already circulating in our community. It was the first report of community spread in the U.S. “The Seattle Flu Study was meant to help us prepare for a possible pandemic, but we assumed that would be years from now,” says Jay Shendure, director of the BBI and one of nine principal investigators for the study. “It happened in year two.”

Jiseon Leah Kim, a nurse at UW Medical Center–Northwest, checks a swab sample taken at the hospital’s drive-thru testing site.

The BBI team responded immediately. Investigators worked with the Washington State Department of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Public Health–Seattle & King County to translate their research and resources into effective public-health action. On March 23, with funding from Gates Ventures, the Seattle Coronavirus Assessment Network (SCAN) was launched.

Using the swab-and-send home test developed for the Seattle Flu Study, SCAN has sent more than 17,500 free testing kits to people in the region who are symptomatic and asymptomatic.

If there’s a silver lining to this pandemic, it may be that it has spurred unprecedented levels of collaboration—across health systems, government entities and private foundations. “People are going out of their way to pull down barriers so things can get done,” Shendure says.

Meanwhile, in early January, Dr. Keith Jerome, head of the UW Medicine Virology Division and director of the UW Virology Laboratory, doubted that the virus they were tracking in China would come to the U.S.—but he knew it was better to be prepared. He and his team began working on their own COVID-19 test. In order to get emergency use authorization from the FDA, they needed a sample of the virus. But before they could have one shipped to their lab, the virus found them.

In late February, amid their own internal testing for respiratory viruses, the lab team uncovered the second reported case of community-spread COVID-19 in Washington state—just days after the Seattle Flu Study had found the first one.

“It was clear that the pandemic was going to be significant, and our testing capacity would be instrumental in helping the state weather the storm,” says Dr. Geoffrey Baird, professor and interim chair of the UW Department of Laboratory Medicine. “I also realized how much it was going to cost.”

Because Baird’s department is a prominent reference laboratory, it has a relatively large reserve, which is invested back into faculty, staff, instruments, education and test development. Baird decided to spend down the reserve in order to ramp up COVID-19 testing.

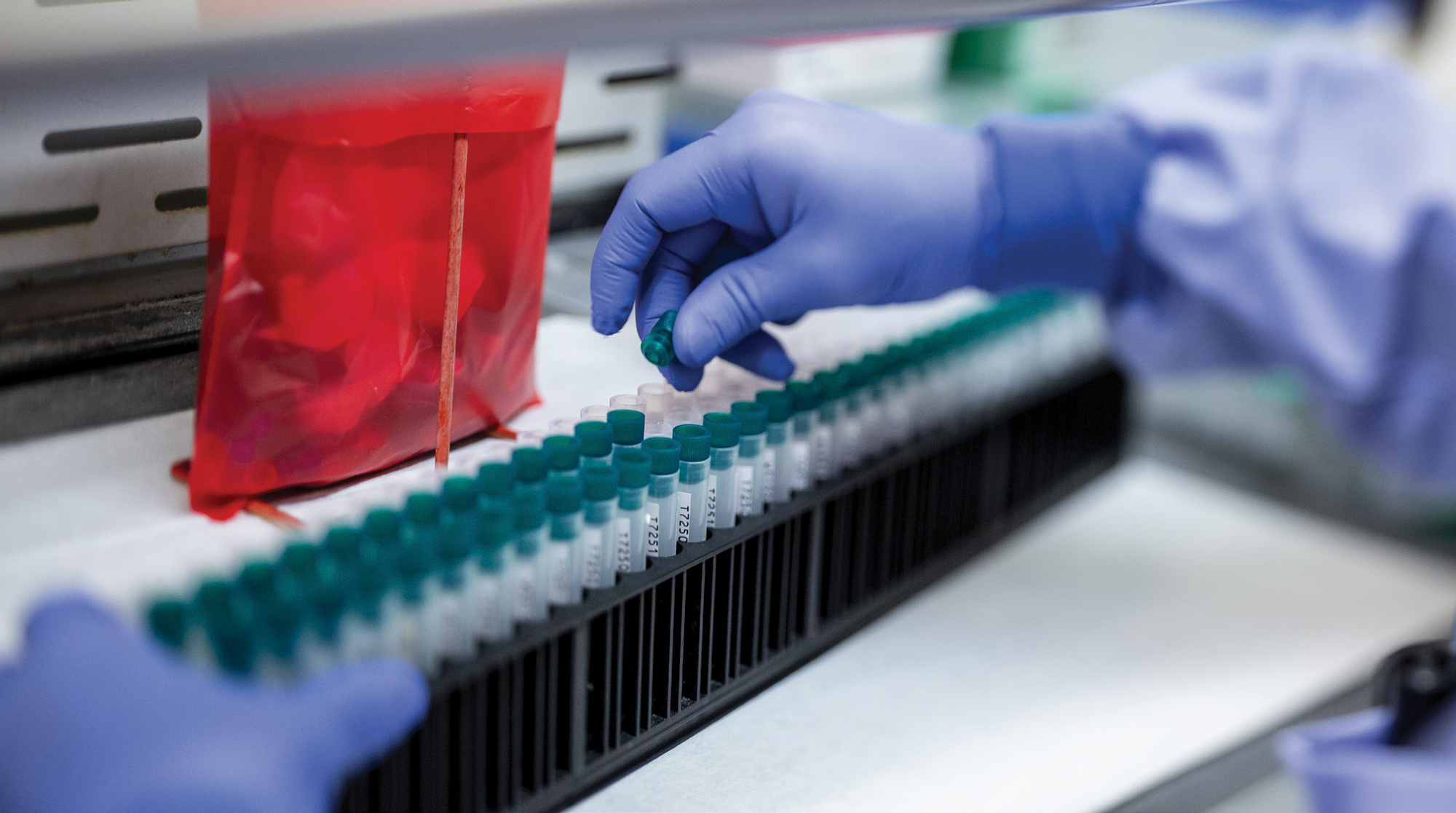

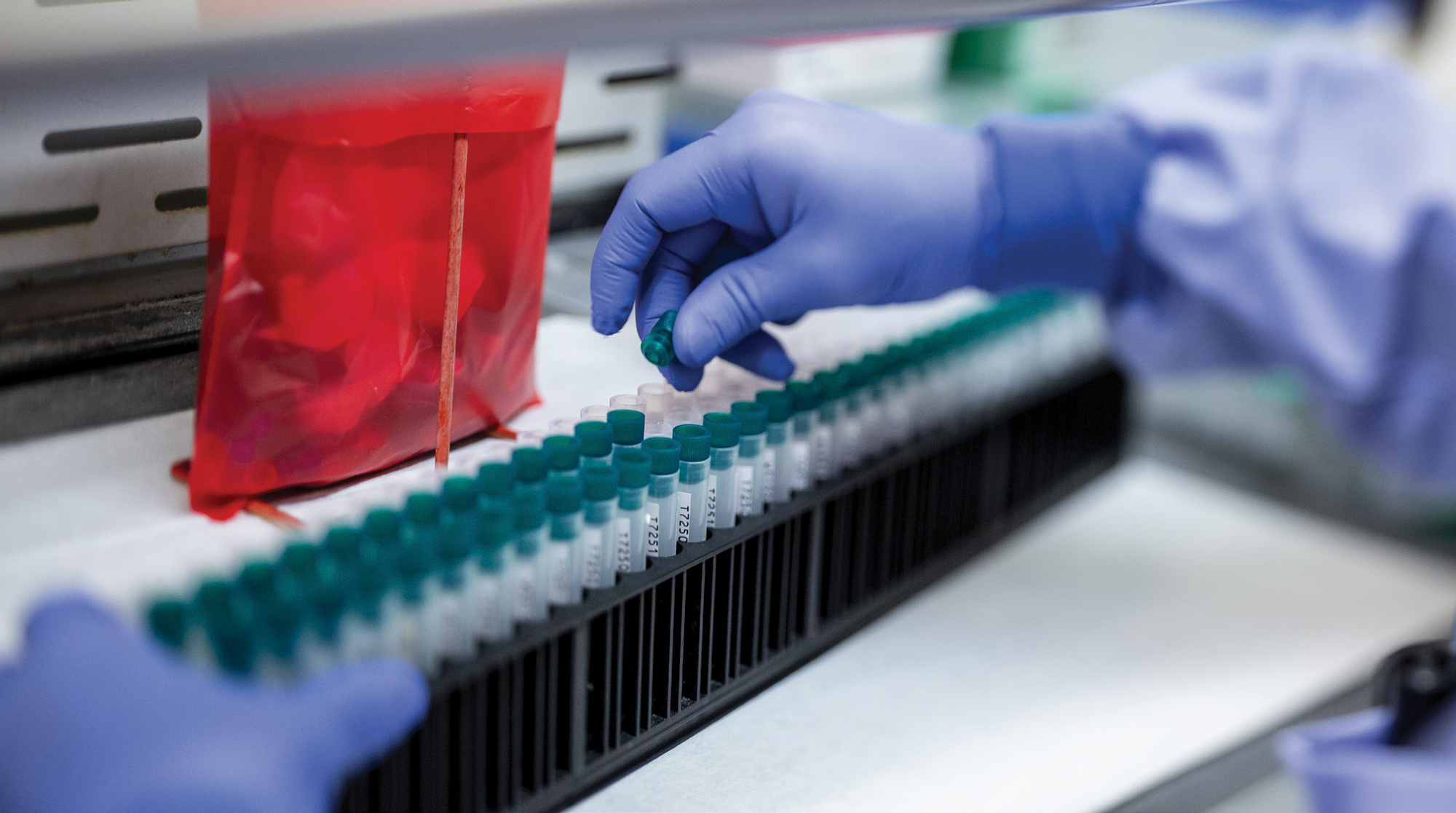

It wasn’t an easy decision, but it was the right one. The UW Virology Lab quickly became the state’s largest test provider, able to handle 8,500 tests a day. For the first few months of the pandemic, the lab provided over 50% of the state’s testing. And while the department’s reserves are depleted, Baird hopes that most will be replenished by federal, state and philanthropic dollars.

Baird had the full support of his colleagues, including Jerome. “This kind of pandemic requires a shift in thinking,” Jerome says. “We will deal with the costs later. Right now, our first obligation is to the health of the people of Washington.”

While the Virology Lab continues COVID-19 testing, it’s also working on large-scale serologic tests—blood tests that show whether someone has had the virus. The lab is also supporting vaccine development and operating a robust genetic sequencing program. In fact, Jerome notes, UW Medicine is one of the largest depositors of coronavirus genomes in the U.S.

“The sprint of our COVID-19 response is clearly going to become a marathon,” says Baird. “The entire UW Medicine health system faces a financial crisis, as do many health systems, and indeed the whole country. So it will continue to be a challenge to fund our COVID-19 response in the coming months.”

Despite the obstacles, Jerome notes that in retrospect, Seattle was actually a good place for the virus to land first. The expertise of the BBI and the UW Virology Lab, along with UW Medicine’s deep strengths in research and patient care, continue to be powerful weapons in the fight to stop the spread of COVID-19. “Between our program getting ready for testing just in case it came here, and groups like Seattle Flu Study looking at the population in a broad way, we were incredibly well prepared,” he says. “We are built perfectly to respond to something like this.”