The people who work in UW Libraries are, by nature and profession, people who want to preserve the knowledge that helps us understand our cultures and histories. After all, that is the Libraries’ mission—to connect people with knowledge. Because of this charge, the UW Libraries celebrated the grand opening of a new Conservation Center last year that has significantly expanded the Libraries’ capacity for conservation.

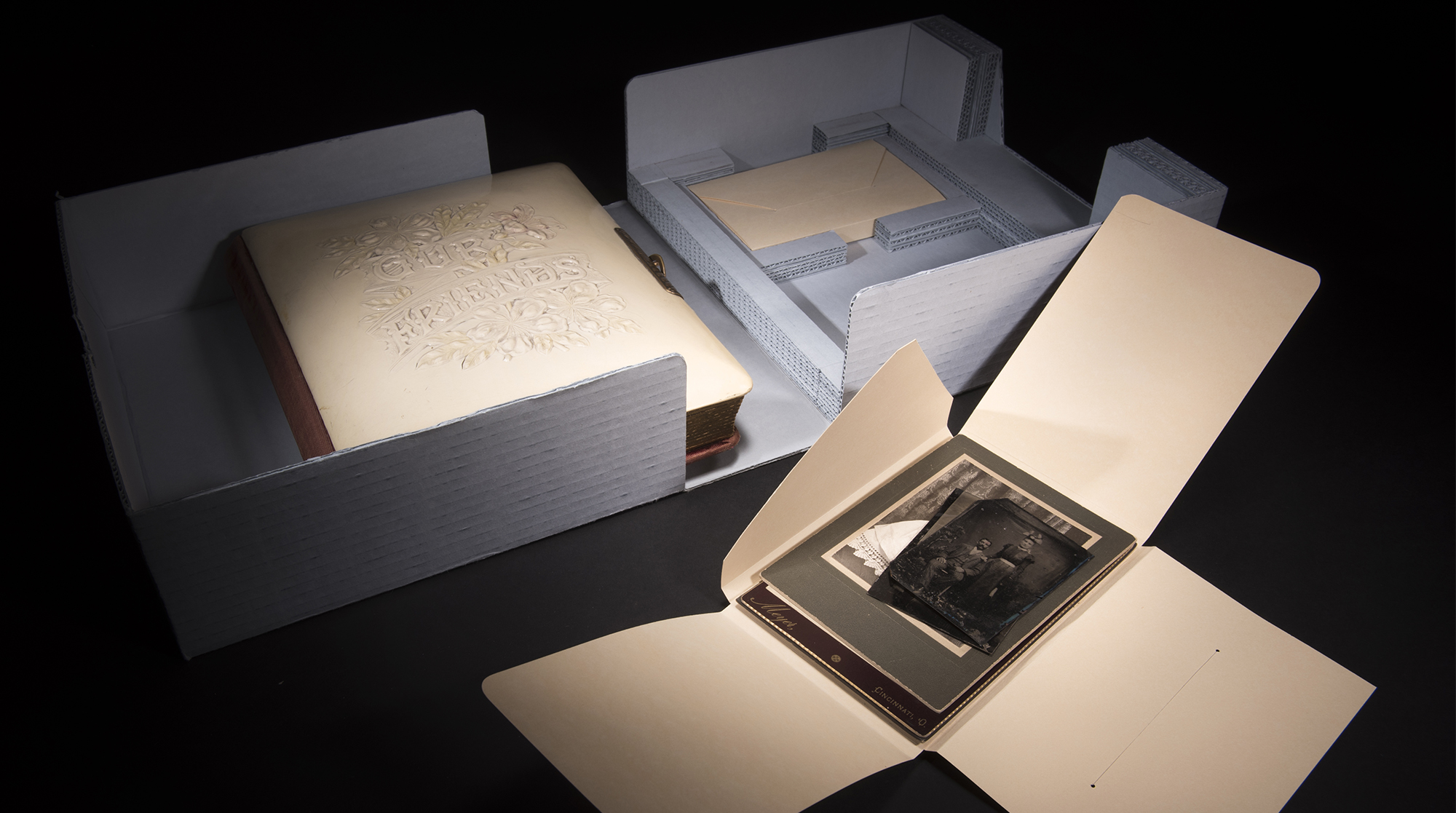

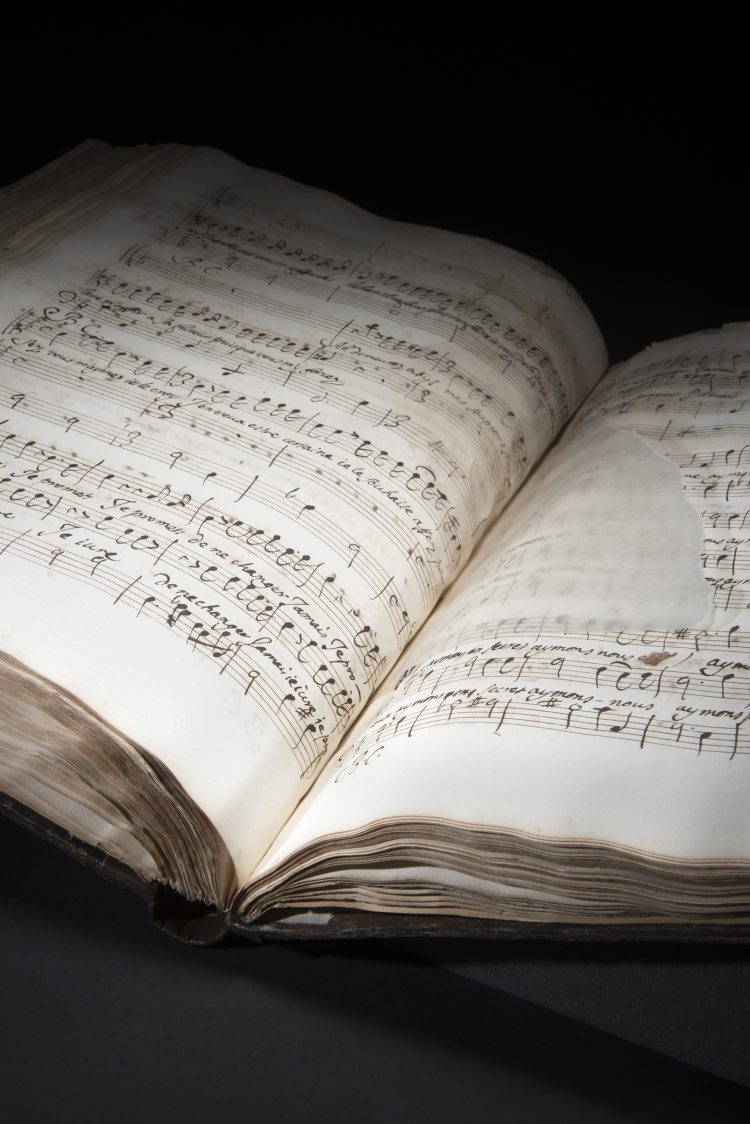

The spacious, new quarters on the fifth floor of Suzzallo Library includes a wet lab replete with fume hoods, humidification domes, suction tables and other sophisticated tools to perform facelifts on rare, older and damaged materials. These new tools allow conservation staff to tackle work they simply couldn’t do in the past due to lack of ventilation and equipment.

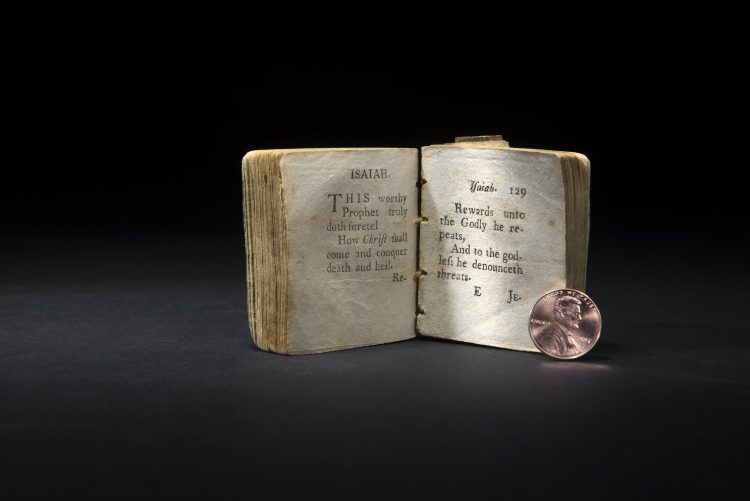

When I visited the center, Justin Johnson was examining a rare 17th century opera score composed by Jean-Baptiste Lully and written in an unidentified hand. Johnson was researching and developing a treatment plan for the manuscript as well as comparing it with others by the same composer to see if he could determine if it was written in Lully’s hand.

Johnson was hired four years ago, thanks in part to a $1.25 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Johnson previously worked as rare book conservator at the renowned Huntington Library. This new position enables the UW Libraries to focus more attention on the conservation of its special collections.

Since then, Johnson has repaired hundreds of rare materials, and more than 800 donors have contributed to an endowment to permanently fund the senior conservation position with gifts ranging from $5 to $437,000. It’s nothing short of a community commitment to the preservation and dissemination of knowledge.

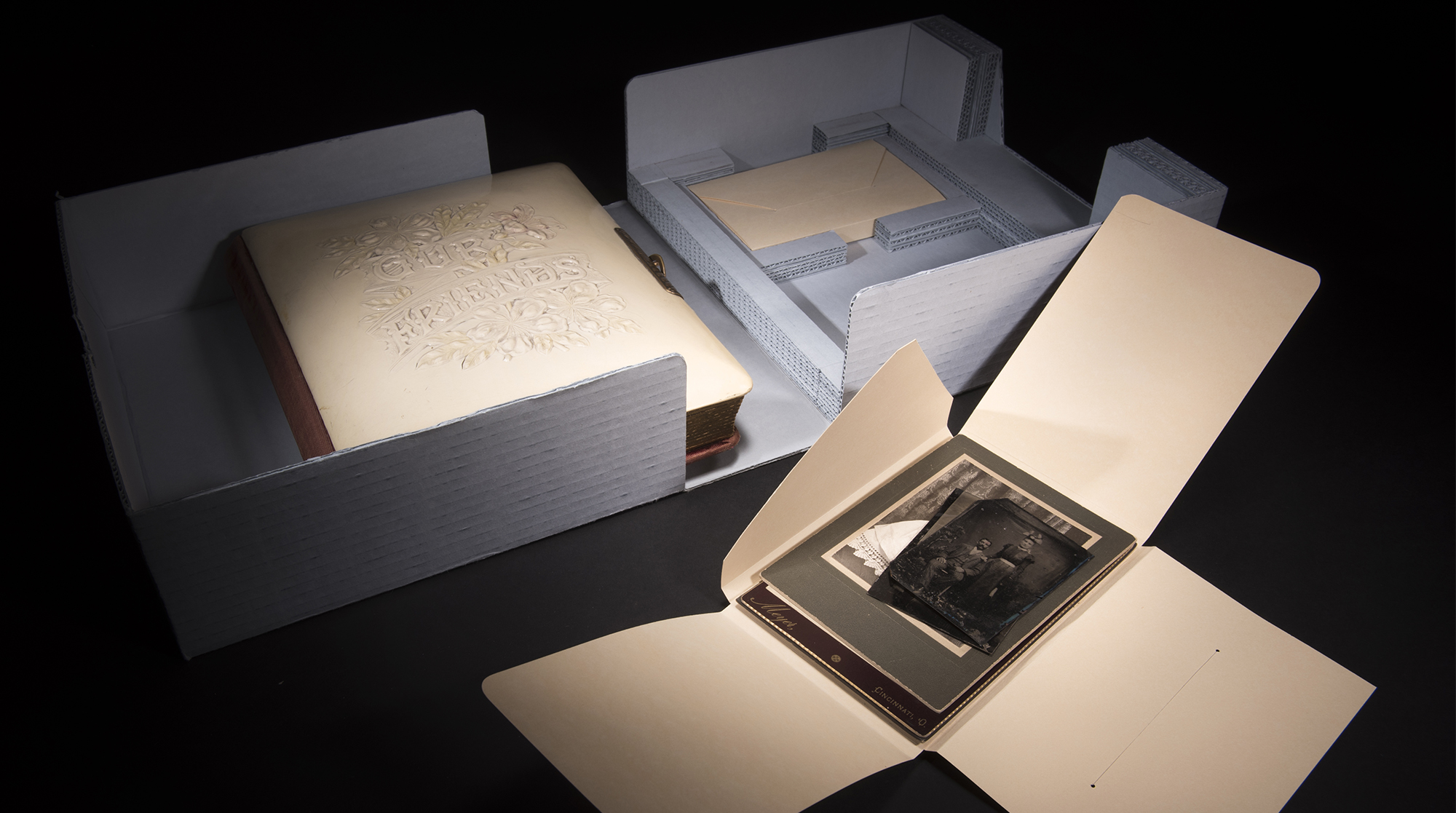

A miniature or “thumb” Bible that was printed in 1794 and dedicated to George Washington needs to have its two-inch-tall cover repaired.

A fundamental text of Western medicine by Hippocrates is ready for resewing on alumtawed thongs.

When it comes to removing old tape, these are the tools of the trade.

A damaged 400-year-old Lully opera score requires careful examination before repair can begin.

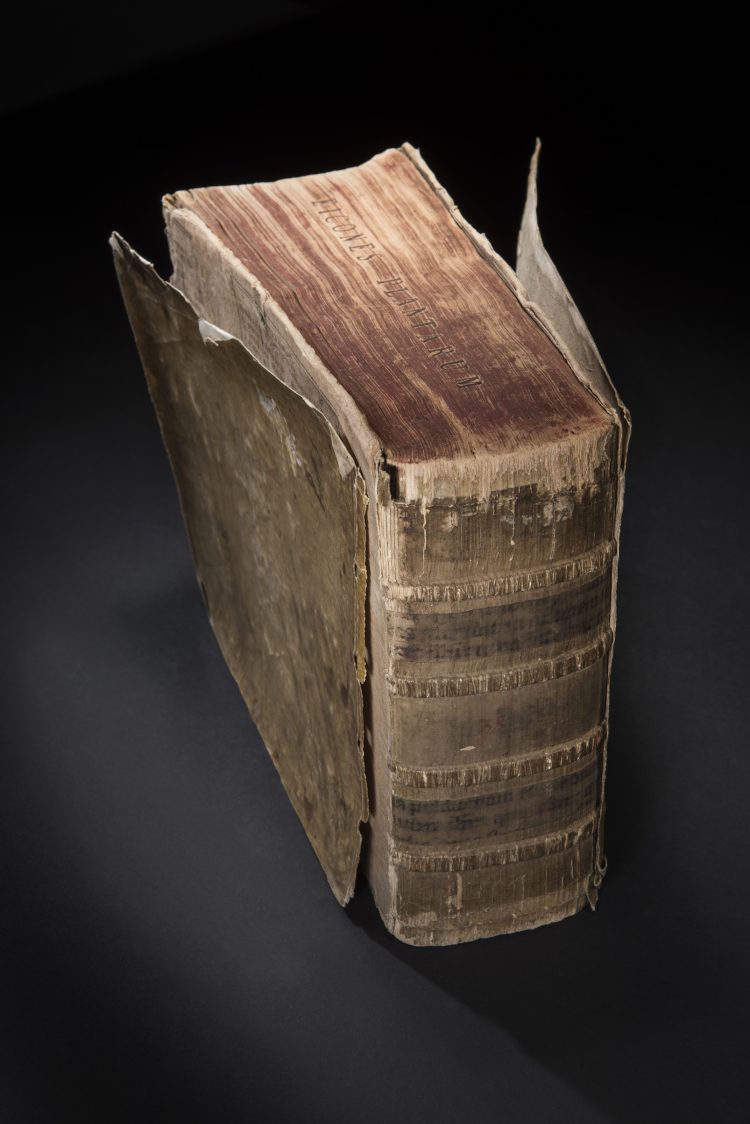

A heavily used late 16th-century botanical encyclopedia awaits repair.

Unfortunately, the 400-year-old opera manuscript was not in great shape, having been previously damaged by water long before it arrived at the UW Libraries. In addition, extensive tears and losses in the pages were repaired by well-meaning individuals who used tape, glue and various varnishes that were readily available to mend the torn pages. In the end, these repairs caused further damage as the adhesives and tapes have discolored or become brittle with age. “Using ultraviolet light,” Johnson explains, “we’re able to distinguish between damage caused by human intervention versus damage caused by old age and exposure.”

A refurbished card catalog now holds small tools used by Preservation Services staff.

Nearby, summer conservation intern Christine Manwiller is hard at work repairing a second edition of Vancouver’s “A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean, and Round the World” that is often used in teaching undergraduates. Carefully, she lifts the leather on the original binding to repair the spine and make the book once again available for use in the classroom.

One student who especially appreciates the new Conservation Center is Sarah Faulkner, a doctoral candidate who is working on her dissertation in English literature. She’s concentrating on the work of women writers who were contemporaries of Jane Austen.

Faulkner depends on access to 200-year-old texts, including pamphlets or texts that were published with books’ original editions (but not in later editions). Until now, some of the texts Faulkner needed were inaccessible because they were falling apart. But the center’s work means she can get her hands on these materials.

Clean, well-lit and spacious, the Conservation Center is far removed from the eras in which so many items now being treated were originally created. Because of the work being done by Johnson and others, books and manuscripts (many over 300 years old) can be safely held and read by students, faculty and researchers.

More than 6 million people walked through the doors of the UW Libraries last year, so the demand is high. Working behind the scenes, conservation and preservation staff will continue to ensure that the library collections are ready and available for these visitors—for new discoveries, ongoing research, or for the simple joy of finding a handcrafted book that was written by candlelight.