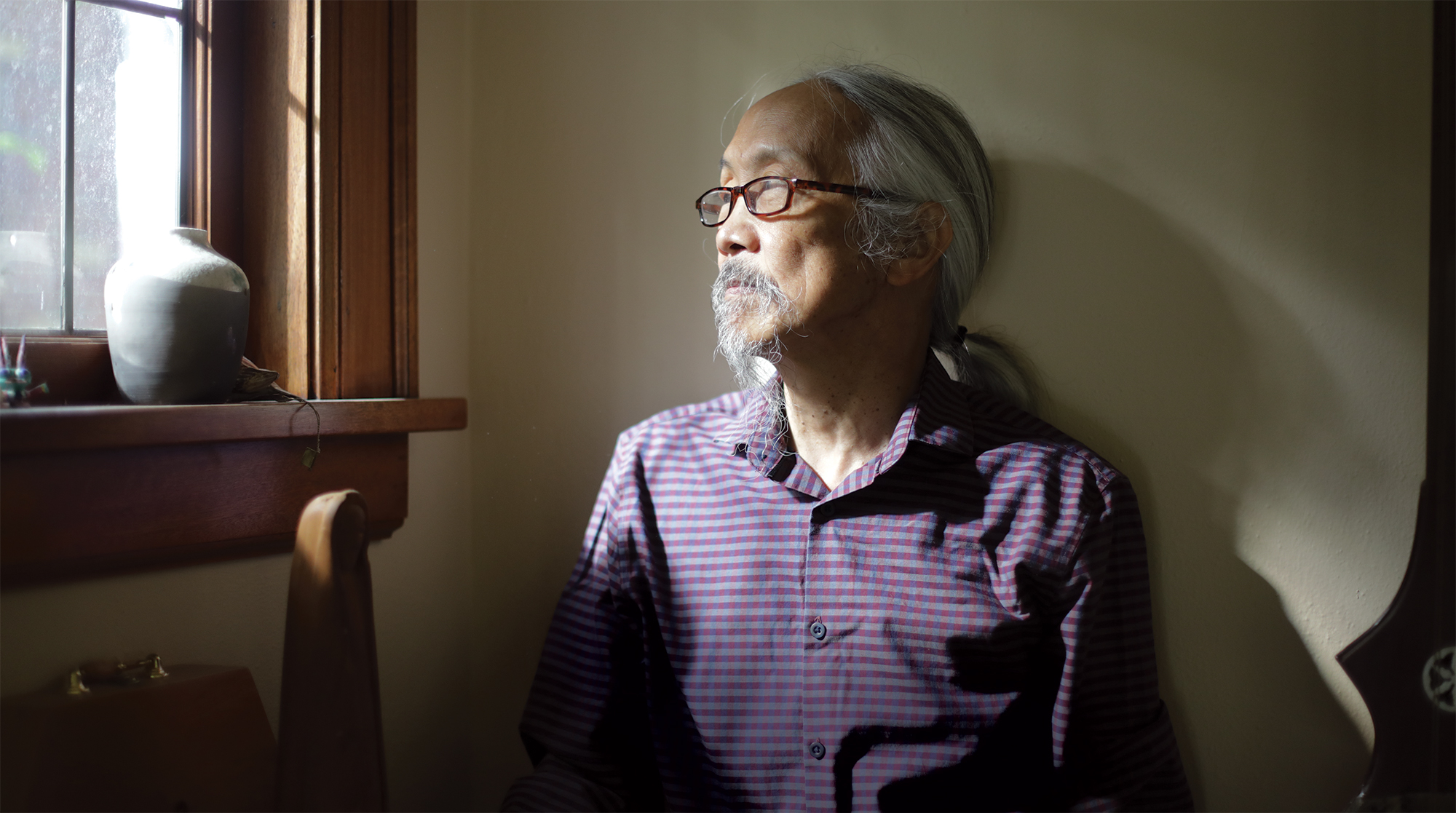

It wasn’t easy for a young Filipino American man with a love of science and a passion for community service to dream big in the 1970s. As an undergraduate at the UW, Fernando Vega once brought home a glossy brochure about becoming a medical technician and showed it to his father. His dad was blunt: “If you’re going to do that, you might as well be a doctor.”

Vega, in his early 20s, began volunteering as a patient advocate at the Country Doctor on Capitol Hill and the International District Community Health Center, where patients were treated free of charge. He observed the doctors as they gave their time to treat any ailment that came through the doors, from sexually transmitted diseases and drug problems to the flu and mental health issues. The doctors seemed to enjoy their work and feel good about helping patients, who were mostly young people who had no insurance. Vega thought, “I could do that – I’d like to do that, become someone like that.”

Even as a kid, Vega was fascinated by the way the physical world works and spent hours pouring over the Time Life Science book series, intrigued by polymers. He loved going on field trips with his father, who worked in quality control for various Alaska canneries. Born in Seattle, Vega spent most of his first six years in the Philippines, where he spoke Tagalog and studied English from his father. Vega’s school years were all in Seattle, where his mother taught in the public-school system. But with roots in two cultures, Vega struggled to find his identity. During his years at Garfield High School, Vega’s community was mostly other kids of color.

In those days, medical school was mostly the purview of white males, but the UW’s Educational Opportunity Program offered Vega a way in. During his senior year at the UW, Vegas was named “Asian Scholar of the Year” at the EOP Banquet. He majored in cell and molecular biology, his grades were good, not great, but his science scores on the Medical College Admission Test were higher than the class average. And, perhaps most important, his motivation was off the charts. Having grown up with community service values of the First Baptist Church, Vega was a firm believer in health care as a right. He was involved as an organizer and advocate at the inception of local free clinics and committed himself to a career helping others.

Vega went to medical school at the UW, where he was the only Filipino American in the class. “It was tough,” he says. “I had to learn to study, develop habits and discipline. I was nervous as hell. Here was this minority student who had the weight of expectations: I could not fail.”

He persevered and became the first Filipino American to graduate from the UW School of Medicine in 1978. One of the lifelong habits he developed there was working long hours, first as a phlebotomist at UW Medical Center Montlake, to help pay his medical school expenses; then, during his three-year residency at Altoona, Pennsylvania, where he also worked after-hours as an emergency room physician.

“It was actually quite enjoyable,” he recalls. “You are on your feet. You take whatever comes off the street. You are with people during a very intense time, so there is a deep connection and then you never see them again. You read about it afterward – what went right, what went wrong. But you are doing something … I felt validated.”

Much as he loved the challenge of ER work, Vega’s goal was family practice. He wanted to get to know his patients over time, to develop relationships and see the benefits of his work. After returning to Seattle in 1981, he opened a private practice at what was then Providence Medical Center (now Swedish Cherry Hill). He signed an expensive lease, bought art for the walls, and waited for patients to flock in, admitting, “I had no idea what I was doing.” As the first few patients ventured in, Vega, ’74, ’78, found he had plenty of time to get to know each one, jotting down their histories, observing their behavior. Taking time to listen carefully became a hallmark of his practice. Still, money wasn’t exactly pouring in, and with a young family to support, Vega had to subsidize his clinic by working as an ER physician at Providence and Cabrini hospitals, as well as at other urgent care centers.

“Half of what we did 20 years ago was wrong. Half of what I do today is wrong; I just don’t know which half.”

Fernando Vega

It was during that time, in the early 1980s, that a pivotal event in Vega’s career occurred. An old church friend asked him if he would be willing to sponsor a traditional Chinese medical doctor at his clinic. At the time, acupuncturists were not licensed in Washington state, so Dr. Amy Chen, recently arrived in Seattle from China, was not able to practice independently. Having her at the office drew a different type of patient to Vega’s clinic, and he began to ask questions. As he witnessed the healing power of acupuncture and herbal remedies, Vega’s mind opened to other medical skills and philosophies. He had come out of medical school feeling like he knew everything. Now he wondered: “What else is there?”

Soon other like-minded physicians joined the clinic, along with a naturopath and a physical therapist, and Seattle Healing Arts was born. Alternative health practitioners and their patients would come to Vega when they needed conventional medical care or a doctor with hospital privileges. Among them was pioneering Seattle naturopath John Bastyr (1912-1995), for whom the burgeoning alternative medicine university, with campuses now in Kenmore and San Diego, would later be named.

Known for his practical approach to healing, Bastyr graduated from a chiropractic college and completed a residency at a Seattle hospital before beginning his practice in the mid-1930s, during the Great Depression. His palpatory skills as a chiropractor and keen observation helped him diagnose illness. “He saw things no one else did,” Vega says. Bastyr grew up in North Dakota with a mother who was an herbalist and a father who was a pharmacist and learned to work with whatever tools he had at hand – physical manipulation, herbs, homeopathy. He treated patients for free if they were short of cash. He delivered many babies during his more than five decades as a family doctor, and in the 1950s, Bastyr helped establish the National College of Naturopathic Medicine in Seattle. The school later moved to Portland.

Across the country, interest in different approaches to medicine was growing. In the 1980s, the American Holistic Medical Association met in Seattle and brought innovative physicians such as Bernie Siegel and Christiane Northrup to town before they became well known. Deepak Chopra and Andrew Weil, then relatively new authors, were also featured. Hearing them, meeting some in small groups and learning about new ideas in medicine inspired Vega: Chopra for his spirituality, Weil for his practicality, Northrup and Siegel for thinking outside the box. For his own edification, and for the historical record, Vega videotaped long interviews with a dozen prominent physicians working outside the mainstream, beginning with John Bastyr in 1994. Still, Vegas resists the arcane classifications – Alternative Holistic, Integrative, Complementary – each with different nuances of meaning. He is content to be considered a family doctor.

“Physicians ultimately learn the most from their practice with patients,” Vega says. Each time a patient would tell him about a technique or method that got results – osteopathy, visceral manipulation, vitamin infusions – he would study it or consider training in it. And, he points out, many ideas considered far-fetched in the ’80s are now widely acknowledged: the importance of gut flora; the effect of diet on inflammation; the use of Neti pots for sinus irrigation. “Half of what we did 20 years ago was wrong,” Vega says. “Half of what I do today is wrong; I just don’t know which half.”

Over the years, Vega has taught classes at the UW’s School of Medicine and the School of Public Health, and medical students and residents still do rotations with him at Seattle Healing Arts. The clinic has moved several times since its inception, first to offices near Green Lake, then to a converted building near Roosevelt, and finally, in 2017, to a medical building at Northgate. A few years ago, Vega expanded the title of the clinic to include Seattle Sexual Health. Vega says taking care of patients’ reproductive and sexual problems has always been integral to his work as a family doctor and that as his patients age along with him, they develop new concerns. But it wasn’t until he included that in the clinic title that some patients felt comfortable opening up, telling him, “Oh, what a relief, I can talk about this.”

In 2004, Dr. Martina Koller joined Seattle Healing Arts and in 2012, she and Vega married, the second marriage for both. Now they spend most of their time together, caring for patients. Even on weekends, they often drive around making house calls to longtime patients or family members who need assistance. Particularly this year, during the COVID-19 pandemic, they have donned protective gear to check in on patients who are housebound, sometimes delivering oxygen or taking nose swabs for testing, listening to lungs, doing whatever they could to keep people out of the hospital.

The world of medicine changed drastically in 2020. The video-screen consultations of the COVID era bear little resemblance to the kind of hand-on diagnostics Vega learned in medical school in the 1970s. He still prefers to start an exam by looking at his patients’ hands, feeling for temperature, tension, muscle strength. He is adept at percussing lungs – an old diagnostic skill now seldom practiced, he says – listening for any muted sound of obstruction the way a carpenter might search for the stud in a wall. Nevertheless, Vega – always happy to explore new technologies – appreciates the convenience and safety of video consultations.

There have been other changes over the years, too. One is the advent of the well-informed patient. Vega says he first witnessed that shift in the 1980s with AIDS patients. Information about the deadly new syndrome was scarce and many doctors were at a loss about treating it, so gay men, in desperation, had to research the latest developments on their own. “They’d come to me with a stack of medical papers,” Vega says, and he would learn along with them. Now, with so much information a click away, patients generally are better informed than they once were, a development some doctors lament but Vega welcomes.

In the decades since medical school, Vega has learned so much that now, at 69, he feels it would be a waste of all that experience to simply retire. About five years ago, he stopped accepting new patients and began thinking about how to transition from the responsibilities of running a clinic to seeing patients part-time. As always, he wants to continue advocating for greater exploration of healing and medicine.

“That’s the value of Seattle Healing Arts,” Vega says. “There are always rifts and arguments between different disciplines, but if you can get through the language barrier in the context of mutual intentions, real discoveries can happen.”