The legacy

of ‘No-No Boy’

The legacy of ‘No-No Boy’

UW professor protects the legacy of ‘No-No Boy’

Decades ago, he built a foundation for Asian American literature; now, a UW professor is still protecting an alumnus’s classic novel.

By Vince Schleitwiler | December 2019

Shawn Wong knows the power of a good story. The longtime English professor has edited anthologies, written novels and helped turn one book into a film. He has taught literature, fiction and screenwriting, and through the Red Badge Project, teaches storytelling to veterans suffering from PTSD and related disorders.

But Wong’s place in literary history was already secured in the 1970s, even before his first novel was published. Along with a small group of writers, scholars and activists, he rediscovered and reprinted overlooked classics by Asian American authors, demonstrating to the world that Asian American literature was a distinct, proud tradition.

So last spring, when the publishing behemoth Penguin Random House released a new edition of one of those books, John Okada’s “No-No Boy,” while ignoring the rights of the Okada family, he knew how he would fight back. On social media, he posted an image of the copyright claim he’d filed in 1976 for the author’s widow, and shared memories of his adventures as a do-it-yourself publisher, hawking copies of the novel from the trunk of his yellow Mustang.

“What Penguin doesn’t understand is that books belong to people, to families as well as writers,” Wong wrote.

The literary community responded, and Wong’s campaign to push Penguin to recognize the Okada family’s rights went viral. Statements of support appeared from prominent writers like Viet Thanh Nguyen, David Henry Hwang and Jamie Ford. Influential booksellers, including the Elliott Bay Book Company and the University Book Store, returned their copies to Penguin and reordered the long-standing edition, authorized by the Okadas, from UW Press.

Within days, articles appeared in the national media, including The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, NBC Asian America and the front page of the Seattle Times. How could they resist a good David-and-Goliath story—one man facing off against a giant multinational conglomerate?

Sure enough, Wong’s campaign succeeded. By the end of summer, Penguin reached an agreement—UW Press continues to sell the novel exclusively in the United States, and, with the Okadas’ approval, both publishers are working together to facilitate international sales.

Stories are powerful. As with most good ones, though, there’s still much more to be told.

* * *

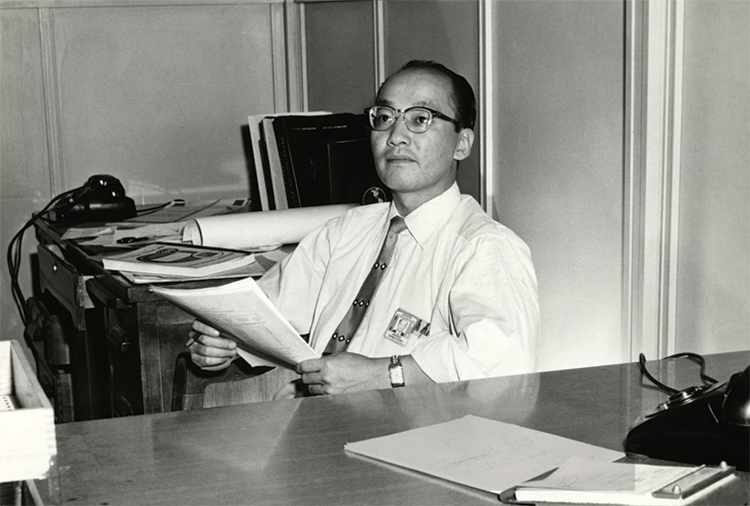

In 1957, the year “No-No Boy” was published, John Okada worked as a technical writer. He died in 1971 and never got to enjoy the success of his book.

In 1971, a 47-year-old UW English alum named John Okada died of a heart attack. A chain-smoking, workaholic father of two, he’d been a “Mad Men”-era advertising copywriter, a technical writer in the Cold War defense industry and a mild-mannered librarian.

Meanwhile, on the side, he’d published a novel with a small publisher based in Japan and Vermont. The Charles E. Tuttle Co. printed “No-No Boy” in 1957 in a hardback run of 1,500 copies and still hadn’t sold them all when Okada died. In the meantime, he had been slowly working on a second novel about the Japanese American immigrants of his parents’ generation, which he left unfinished.

His widow, Dorothy, couldn’t find any takers for his manuscripts, so she threw them out. “I have him in my heart, and I have him in my head,” she explained later. “What more evidence do I need?”

The literary life can be cruel, and not all good stories reach an audience.

Indeed, Okada’s own story was remarkable, as Frank Abe, Greg Robinson and Floyd Cheung revealed in “John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy,” a 2019 American Book Award winner from UW Press.

A once-vibrant Japanese American literary scene had been devastated by the war, and Okada died before he was able to find his audience.

The night after Pearl Harbor was attacked, Okada, then an 18-year-old undergrad, girded himself for the impending war and racist backlash by writing a poem. “I Must Be Strong” was published anonymously in The Daily four days later. That February, the FBI came to the family business—the Yakima Hotel in Seattle’s International District—to arrest Okada’s father, Yoshito. Separated from the family, Yoshito was thrown into a detention center, and eventually sent to a camp near Missoula, Mont.

Meanwhile, Okada, his mother, four siblings and other Seattle Japanese Americans, were incarcerated, first in barracks at the Puyallup fairgrounds, and subsequently at the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho. His family was still there when Okada volunteered for the Army, where he flew 24 missions intercepting Japanese radio communications for the Military Intelligence Service.

Japanese American MIS veterans were sworn to secrecy after the war, so Okada couldn’t tell his own story in his novel. Instead, he drew on the memories of an old classmate from Broadway High and the UW, Hajime Jim Akutsu, one of a number of Japanese Americans who’d resisted the draft while their families remained behind barbed wire.

For this act of conscience, they were tried, convicted and imprisoned, and—despite a postwar presidential pardon—faced decades of ostracism within their community. In “No-No Boy,” Okada fashioned a somewhat different story, of a bitter and confused resister fresh from prison, the slowly dying veteran who befriends him and a community still reeling from the trauma of incarceration.

Good stories Okada had in abundance. But a once-vibrant Japanese American literary scene had been devastated by the war, and Okada died before he was able to find his audience.

Then, a few months later, a scruffy group of young Asian American writers came calling.

* * *

Shawn Wong knew he was going to be a writer while still an undergrad at San Francisco State University. Unfortunately, he later wrote, “I realized I was the only Asian American writer I knew (and I wasn’t very good).”

His mentor, the legendary novelist Kay Boyle, introduced him to a graduate student, Jeffery Chan. Through Chan, he met Frank Chin, another writer. Together, they hunted through used bookstores for evidence of other Asian American writers.

In an anthology of Fresno, Calif., poets, they found Lawson Inada, who was teaching in Oregon. The four of them founded CARP, the Combined Asian American Resources Project, and befriended a who’s-who of 1970s writers of color, including Ishmael Reed and Leslie Marmon Silko.

They also dug up an older generation of writers, including Toshio Mori, Hisaye Yamamoto and Wakako Yamauchi. Soon, they had enough new and rediscovered material for an anthology, “Aiiieeeee!,” which was rejected by numerous presses before Howard University Press’ Charles Harris finally agreed to publish it.

But of all the books they rediscovered, the most influential—the proof-of-concept for their vision of an Asian American literary tradition—was “No-No Boy.”

Tragically, they just missed meeting the author, but they made a pilgrimage to see his widow, and began to spread word about the book like missionaries. When it went out of print, they enlisted the Japanese American community in a letter campaign to get it reprinted.

They targeted the University of Washington Press, which asked them to raise $5,000 to fund the printing. Instead, they decided to publish it themselves. They pooled savings, scrounged money from Okada’s brothers, and took out an ad in a Japanese American newspaper, offering a discount for advance purchases.

“He is so unassuming, it is sometimes easy to forget that we have a legend in our midst.”

Anis Bawarshi, UW English professor

And the readers showed up. The first CARP printing sold out before it arrived, and they ordered another. Realizing they’d missed out on a hit, the folks at UW Press called back, but Wong insisted that the press republish other authors first. They agreed, beginning a partnership that has continued for over 40 years, giving rise to an unparalleled catalog of Asian American classics.

Eventually, Wong agreed to let the press take over the reprint of Okada’s novel, and introduced the press to the Okada family. “We’ve built a trusted relationship with them since we first published “No-No Boy” in 1978 and we’ve run all major decisions by the Okadas,” says editor-in-chief Larin McLaughlin. “We’ve sold over 160,000 copies of the book, and sales since 2014 have increased every year.”

In recent years, the press has been updating its Classics of Asian American Literature line with new editions of authors like Carlos Bulosan, Toshio Mori and Bienvenido Santos. This year, the press released an expanded version of David Wong Louie’s “Pangs of Love,” with a foreword by Viet Thanh Nguyen, and reissued works by Mary Paik Lee. Others are forthcoming.

* * *

Bigger news is on the way. Wong is going back to his publishing roots, collaborating on a new UW Press fund to support Asian American titles. The first of these “Shawn Wong books” will be a reissue of Louis Chu’s “Eat a Bowl of Tea,” with a foreword by novelist Fae Myenne Ng. Meanwhile, in November, UW Press released a third edition of “Aiiieeeee!,” the CARP anthology that reintroduced Okada and others in 1974. Ironically, the release was made possible by a separate decision by Penguin, which ceded the book’s rights.

“Aiiieeeee!” is long overdue for reconsideration by readers and scholars. University of Oregon professor Tara Fickle, who wasn’t born when it was first published, wrote a foreword and has been helping to digitize Wong’s impressive archives. “Working with Shawn and the archive has given me a completely new perspective on the editors and the historical moment that gave birth to this anthology. There are so many more voices here,” she says. “I hope our newest edition really pays tribute to them as well.”

After all these years, now it’s Wong’s own efforts that are being rediscovered. Along the way, he joined the UW faculty, influenced countless students and, with scholars like Steve Sumida and Sam Solberg, helped establish the foundations of the Asian American literary field.

As his colleague Anis Bawarshi explains, Wong’s work has included institutional leadership on equity and inclusion in various capacities, including a stint heading the English Department. “He is so unassuming, it is sometimes easy to forget that we have a legend in our midst,” says Bawarshi, the current chair. “But at a time when we in English and other humanities departments are thinking critically about disciplinary boundaries and their organizing epistemologies—what they include and exclude—Professor Wong has played a crucial leadership role in helping us understand how centering equity can transform and enrich our disciplines.”

One man against a multinational corporation? A struggling author dying in obscurity? Maybe these stories were never as lonely as they seemed. The real story, in 2019 as in the 1970s, is that the audience for Asian American literature is big, passionate and growing.

That’s the power of a good story—it can reveal a whole world that you hadn’t realized was there.

Pictured at top: An illustration based on the original artwork for “No No Boy” when it was published in the 1950s.