Imagine a TV crew interviewing George Washington during the depths of Valley Forge, years before the victory at Yorktown assured American independence.

Or switch channels to see Ted Koppel grilling a French revolutionary a year after the fall of the Bastille but long before the bloody Reign of Terror.

While capturing a dramatic moment during a political revolution, would those crews be able to explain what was happening and predict the future?

A joint U.S.-British television crew is facing a similar dilemma this month as it starts filming a seven-part documentary series on the transformation of the Communist world.

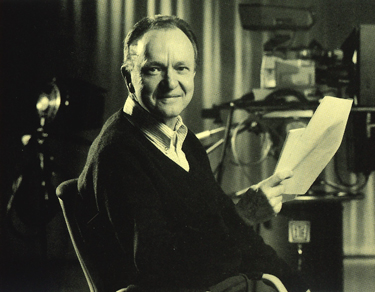

Herbert Ellison

Communism in Crisis: The Second Revolution is the brainchild of UW International Studies Professor Herbert Ellison, who has been trying for five years to launch a series on Marxism in transformation. Now the cameras are finally beginning to roll for a series that will not be seen on PBS or the BBC until mid-1991.

It appears to be an impossible task—making a documentary series about a revolution in the midst of that revolution.

“If we had produced this even a year ago,” Ellison admits, “it would have been out of date very shortly.” He calls 1989 a “year of miracles” and notes that there has been a revolution “from the Yellow Sea to the Elbe.”

But in Communism in Crisis: The Second Revolution, Ellison does not propose to chronicle the events of that year. His is a much more ambitious task: explaining why Communism is in crisis and what might be some of the future alternatives. “The point is not to do a series on the revolution of 1989. It is to do a broad historical series on 20th century Communism.”

Four months before filming started, the East German government opened the Berlin Wall, an event no one predicted. But even if the series had already been finished at that point, Ellison says, it still would have served an important purpose. “For anyone trying to understand what’s going on now, we’re going to provide a very strong historical component.”

“People studying this region always expected this. You just never know when the patience of the people is spent.”

Herbert Ellison, UW International Studies professor

For example, the dramatic changes in East Germany can only be understood by examining the forced Sovietization of the country after World War II and an examination of the slow deterioration of the East German economy. “Many of the problems were evident by the mid-1980s,” Ellison says of that country.

“People studying this region always expected this. You just never know when the patience of the people is spent.”

Still, Ellison admits the sudden opening of the Berlin Wall caught him by surprise. “I don’t think anyone could have expected how rapidly it would come apart,” he says.

If future upheavals occur, they can be included in the series even after the initial shooting, through updating the narration and finetuning the final editing. “We’ll have ample time to integrate the most recent changes,” he says.

Ellison first proposed the series five years ago, when he headed the Kennan Institute in Washington, D.C., but there was little interest. The idea finally got off the ground about a year and a half ago, he added, and since then it has become easier to attract sponsors for the $4-million U.S. contribution.

As the senior adviser, Ellison will co-author most of the shooting scripts, consult with advisers on each program segment, accompany the crew, conduct some of the interviews, and even spearhead the fund-raising efforts.

He will not, however, be the host the way Carl Sagan hosted the TV series Cosmos. “We had a lot of debate about the format,” Ellison reveals. “It is awkward getting someone who appeals to both American and British television audiences. As we began to work on the idea, we realized we would lose so much time having contrived antics for the host, such as climbing over a barricade.”

Instead the series will have an off-screen narrator and will combine current footage with archival scenes. “It’s such a complex subject. Without a host, we’ll have more time for interviews with the ‘real’ actors.”

“It's not often in our lives that there is a great revolution. And this is one of the greatest revolutions in modern history.”

Herbert Ellison

Ellison hopes to line up such luminaries as Mikhail Gorbachev, Deng Xiaoping and Vaclav Havel. Just what makes him think they will sit down in front of his cameras? “They’re very media-oriented. Gorbachev is the most brilliant user of the media among contemporary political leaders. He might well do it, if he thinks this is a serious production.”

Ellison has a panel of distinguished consultants who will guide the filming of each episode. The experts include scholars from Oxford University, Harvard, the University of California, and other institutions plus two UW international studies professors, Nicholas Lardy and Elizabeth Perry.

Ellison is also counting on his advisory committee—headed by Henry Kissinger and including former British Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington—to open some doors that might be closed to other producers. The host for the American broadcasts will be William Luers, former ambassador to Czechoslovakia and currently president of the Metropolitan Museum of New York. During Gorbachev’s last visit to the U.S., Luers was his host in New York City.

The series is an ambitious project—perhaps too ambitious for television. When asked exactly how he was going to explain such concepts as “dictatorship of the proletariat” or a centrally planned economy on television, Ellison replied, “That’s a very good question, and a year ago I wouldn’t have had the slightest idea.”

But since beginning his collaboration with BBC-TV Producer Dale Wolf, Ellison has seen that it can be done. “You have to distill everything to its essence,” he explains. “I have learned a lot about preciseness and economy of language. Wolf can write in two sentences what would take a typical academic two paragraphs.”

As an example, Ellison cited the case of a dissent Lutheran pastor who was freely elected to the Hungarian parliament. The program will follow the pastor in a visit to the parliament and then go with him to his constituency in the countryside. While the viewer watches the dissident interact with everyday Hungarians, the narrator will explain the radical transformation of Hungary’s political system, including the first totally free elections held in a East Bloc country this month.

The series will cover the entire Communist system, not just the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Its programs will examine the condition of private property in China, the clash of values between northern and southern Vietnamese and the Cuban-Soviet relationship.

Following the actual program there will be a short panel discussion on the segment’s topic. It’s another point where current events can update the program content, since the panelists can change during repeat viewings.

In addition to his role as chief consultant, Ellison is also writing a book to accompany the series. “I’ll write it around the same organizational structure, but it isn’t as narrow as the focus of the film,” he said.

Witnessing the change in Eastern Europe after studying 40 years of the Cold War is “a dream come true,” Ellison says. “It’s a new birth of freedom. It’s not often in our lives that there is a great revolution. And this is one of the greatest revolutions in modern history.

“I was deeply moved when I heard about a Czech worker who stood up in his factory and read the opening lines to the Declaration of Independence. We Americans are having our form of government affirmed by people who have been denied that freedom.”

Professor Herbert Ellison becomes dramatic when he discusses the changes in the Communist world: “I think it is a revolution.” The changes are so immense and so shattering that he compares it to a watershed in modern history—the French Revolution.

“You have a political and a social system developed over a very large part of the globe,” he says. “It is an area comprised of one-third of the world’s population.

“Between 1917 and 1950 many countries were brought into the orbit of a system with well-developed ideology, economy, political structure and culture. It was a coherent and unique structure.

“Now that system, for the first time since the Russian Revolution, is being systematically transformed—culturally, politically, economically, socially—the whole lot. That, in my book, is a revolution.”

However, Ellison questions the theory of some commentators, such as Zbigniew Brzezinski, that this is the death of Communism.

“I find it a more dynamic and creative process than that,” he says. “You wouldn’t title the French Revolution ‘The End of France’ or even ‘The End of Monarchy.’”

But he does call Communism a “spent force” in Eastern Europe, noting that the Hungarian party (former named “Communist” but now titled “Socialist”) will probably get 20 to 25 percent of the vote this month. To illustrate the change, he quotes from a Hungarian reformer, who declared, “We don’t want a people’s democracy or a socialist democracy; we want a democracy without adjectives.”

Behind the revolution in Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and the Soviet Union stands Mikhail Gorbachev. How long can the proponent of glasnost and perestroika last in the face of a crumbling Soviet Empire and ethnic strife at home?

“Whenever there is a revolution in progress, there is always the possibility for a counterrevolution. No one can be sure if it will succeed,” Ellison says.

But his own view is optimistic. “They haven’t got an alternative. The people who want to go back, can’t,” he explains. “Gorbachev has modified institutions, transferred power of the party to the government.” For example, the Supreme Soviet used to be a rubber-stamp parliament. Now it has found its own voice. When the Soviet premier submitted names to be confirmed in his cabinet, the Supreme Soviet rejected more cabinet-level nominees that the U.S. Congress has rejected in its 200-year history.

Ellison has great respect for the current Soviet leader. “He is the most skilled political tactician since Stalin.” Though challenged by hard-liners, “at each crucial stage, he wins,” Ellison reports. He also rejects the theory that the Soviet Army could launch a coup, since the army is controlled by the party, and the party is firmly controlled by Gorbachev.

The professor noted that with the exception of Poland under martial law and China in the wake of the Cultural Revolution, Communist countries have never fallen into “a Latin American system of rule by military junta.”

He recites the reply of a young Soviet scholar who was asked what the leaders will do if army generals challenge reform. “We’ll retire the generals,” was his reply, and Ellison notes that Gorbachev has indeed achieved mass retirements.

But during the transition Ellison does see the danger of “a slow drift into anarchy—eventually you might get chaos. A lot of people are worried about that possibility.”

He warns that the transition is enormously difficult, but that the Soviet Union has a tremendous future potential. “It has one of the largest educated populations of any country, enormous natural resources and a great cultural tradition. It has all sorts of things going for it. It’s just that the transition period is very spooky for me.”

Western steadfastness must take some credit for the transformation, he adds. “The containment policy has worked. I’ve heard that comment made to me by many Soviet friends.

“Loyal Communists are very bitter. ‘You forced us into an arms race that bankrupted us,’ they say. This is nonsense. They chose the path of massive armaments to try and break Western willpower.”

But his highest praise is for the reformers themselves. “You can’t forget how enormously important a role the men and women of unbelievable courage and intelligence played, a Sahkarov or Havel for example.”

Asked if he subscribes to a current fad in academic circles—that Western liberalism has “won” and in many respects this is the “end of history,” Ellison responds, “It’s the end of Stalinist Communism, the end of Maoist Communism, the end of a major political movement of the 20th century, but no, it isn’t the end of history.”

Pictured at top: People rally atop the Berlin Wall on Nov. 10, 1989.