Delivering hope Delivering hope Delivering hope

A UW program works to improve maternal health outcomes for Black women and other underserved community members.

By Kim Eckart | Photos by Meryl Schenker | December 2023

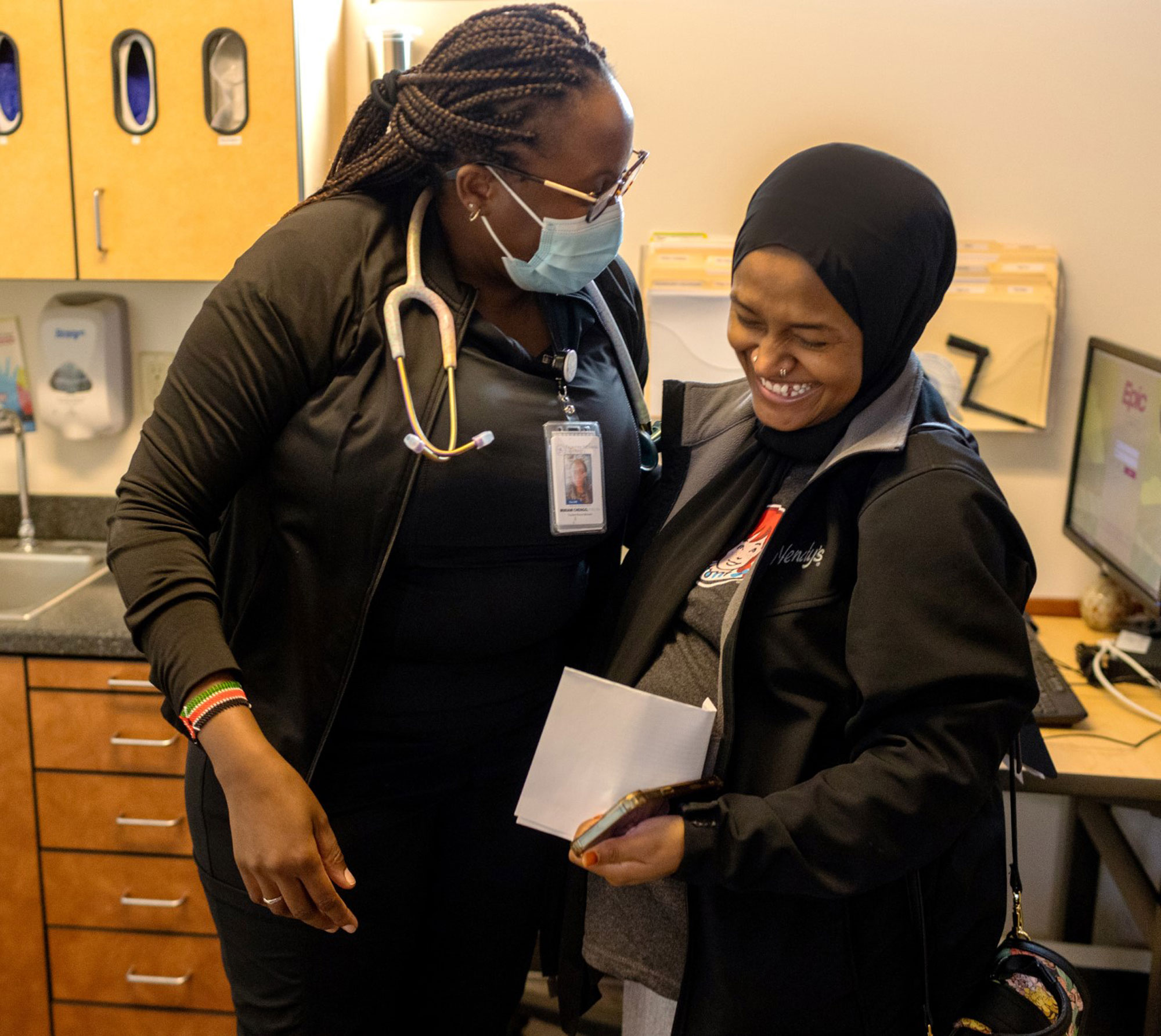

Above: Nurse midwifery student Miram Chengo visits with mother-to-be Fatma, who is enrolled in Heart, Soul and Joy. The mother-to-be was glad to get her own blood pressure cuff so she can take daily readings at home.

Nine months pregnant with her first child, a 31-year-old patient named Mona walks into the Neighborcare Health clinic in Rainier Beach for an appointment with her midwife.

On this visit, she reports a development from earlier that day: Maybe her water broke?

It had. The midwife makes Mona comfortable on a padded, reclining exam table, connecting her to a machine that monitors the baby’s heart rate, and noting that her contractions are few and far apart. Mona can head to the hospital later, she says. She still has the time to gather her things from home.

First, though, at the suggestion of her midwife, Mona signs up for a University of Washington project designed to empower pregnant people to care not only for their own physical health, but also their emotional well-being. Called Heart, Soul and Joy, the research project addresses disparities in maternal health by providing mothers and mothers-to-be tools to monitor their health at home and guidance about mental health, domestic violence, and nurturing joy and pleasure.

“There is a misconception at the heart of research on racial/ethnic maternal health disparities that it’s about problematic Black bodies. But the research should be on problematic health-care systems.”

Associate Professor Rachel Chapman

Ceci Gilmore, ’23, who has a doctor of nursing practice and is the project’s research coordinator at the Rainier Beach clinic, enters the exam room. She shows Mona how to use the free blood pressure cuff, talks about how emotions can fluctuate during and after pregnancy, and that it’s OK for Mona to take time for herself.

“It’s my first baby, and I’m scared to death,” Mona confides. Gilmore, a new mother herself, reassures her: “I’ve been there.”

That sensitivity and encouragement, combined with the tangible tools to monitor one’s physical and mental health, are the foundation of Heart, Soul and Joy. UW students, alumni and faculty across disciplines are working with midwives, doulas and others who provide care to underserved populations to address maternal health disparities. Along with providing patients the resources of self-care and self-advocacy, researchers work with health-care providers to emphasize the value of a patient’s own feelings and observations—authoritative knowledge that is often overlooked. This fall, more than 100 people throughout King County had enrolled in the project that Rachel Chapman, associate professor of anthropology, adjunct associate professor of global health and the study’s principal investigator, hopes can begin to transform the health system.

“This is a story about systems that don’t serve us,” says Chapman, who is African American. “There is a misconception at the heart of research on racial/ethnic maternal health disparities that it’s about problematic Black bodies. But the research should be on problematic health-care systems. How people experience care can be made better, and that can contribute to better policies that unmake those systems.”

The project has wide support from across campus, particularly in the Department of Global Health and the School of Public Health, says James Pfeiffer, professor of anthropology and global health and a co-principal investigator on the project. “Maternal health disparities and maternal mortality are among the greatest challenges in public health we face around the world,” he says. “We believe these disparities are not only urgent in the Global South, but also right here in the United States. We’re bringing tools that are used around the world and applying them locally, with a focus on equitable partnerships with community organizations. And we hope to expand it from here.”

* * *

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Black women are three times more likely to die of a pregnancy-related cause than white women, and the rate of preeclampsia for Black women is 60% higher. But only in recent years has there been an uptick in research and media attention.

Most pregnancy-related deaths are preventable, the CDC points out. The public health agency also notes that while underlying health conditions contribute, so do the social determinants of health, such as the quality of health care and housing and food insecurity, which vary across populations and are rooted in structural racism.

Nonetheless, these tragedies occur across socioeconomic lines. In April 2023, Tori Bowie, an elite Olympic athlete, died of complications during labor. And tennis star Serena Williams has talked openly about nearly dying from a pulmonary embolism after the birth of her daughter in 2017. She described how, in increasing pain, she had to insist her doctors screen her for blood clots. “I fought hard” to be heard, she wrote in a 2022 essay for Elle magazine. “Being heard and appropriately treated was the difference between life or death for me; I know those statistics would be different if the medical establishment listened to every Black woman’s experience.”

These are the stories that make the news. Too often, cases and deaths are just statistics, a pathologizing of a population. That’s where a patient’s authoritative knowledge of self comes in, specifically Black authoritative knowledge, say the UW researchers. Enhancing that knowledge, and empowering the patient to tell a nurse, doctor or midwife that something is wrong, is at the core of Heart, Soul and Joy.

“Being confident in knowing what you know and feeling what you feel, to speak your mind about what you need rather than wait for someone else to make that determination, that is super powerful,” Chapman says. Adds Abril Harris, assistant professor of social work and one of the researchers on Heart, Soul and Joy: “There is a phenomenon of Black women dying. That’s why the Black authoritative knowledge piece is so important for providers to honor, and for us to honor for ourselves.”

Coming together as faculty leads on this project was empowering, according to Chapman, Harris and social work professor Amelia Gavin. Not just as Black women studying maternal health disparities, but as Black women researchers at the University of Washington. “Collaborating with Rachel and her team provided an excellent opportunity to work with researchers of color in examining racial disparities in birth outcomes. It allowed me to explore a core research interest in a more qualitative way with colleagues I admire,” Gavin says.

* * *

Abril Harris, Amelia Gavin and Rachel Chapman are the

UW faculty leaders of the Heart, Soul and Joy project.

The three faculty are committed to approaching the study as a collaboration, among themselves and with the community. Theirs should not be a study that only takes from their participants, treating them as subjects, Harris explains. They’re meeting communities on their terms, and at the same time inspiring and helping student researchers.

Students at all stages of their academic careers have joined Heart, Soul and Joy, from undergraduates to newly minted Ph.D.s. One undergraduate worked on a domestic violence prevention poster that participants receive when they enroll. It features emergency hotline and local service numbers, information that also comes on a card discreetly tucked into a box of lip balm. Another student helped find accessible images and a soothing color scheme for the handout with tips on finding joy—components that would need to translate across languages and cultures. A third, who enrolled this fall in graduate school in public health at Yale University, ran the research team’s check-in meetings and delivered the blood-pressure and health-screening kits to neighborhood clinics.

“This project has taught me how important it is to be informative and to reach people who speak other languages,” says Romina Foroudi, a sophomore public health major who helped develop the project’s messaging around domestic violence. “It makes you question everything you’re doing, because you need to consider what other people will see and get out of it.” As a freshman, she took Chapman’s medical anthropology class and was inspired to join the project. “I want to make sure I’m reaching my communities, especially those that are underrepresented.”

* * *

Before there was Heart, Soul and Joy, there was Mama Amaan. The partnership between the UW and the Somali Health Board of Tukwila piloted the community-based delivery of culturally sensitive pre- and postnatal care. In 2019 and early 2020, local Somali nurses and doulas at five locations in King County provided in-person monthly lessons on physical, mental and emotional health during pregnancy and after childbirth. Chapman led the UW portion of the project with help from alumni and undergraduate and graduate student research assistants.

The issue then was much as it is today: negative health outcomes for women and infants in some of the most diverse neighborhoods in Seattle and South King County, and a health system that leaves many women feeling ignored, discriminated against or profoundly uncared for.

Ceci Gilmore, ’23, who has a doctor of nursing practice from the UW, coordinates the Heart, Soul and Joy program at a Rainier Beach clinic.

But what Chapman and her team learned from Mama Amaan (Somali for “safe motherhood”) was that the value in community-developed and -delivered perinatal care led to a key research pivot during the pandemic. When local quarantine restrictions prevented in-person classes, the team tried a home-based approach that could empower patients to monitor their own health and speak authoritatively with their care providers. Like Mama Amaan, the new Heart and Soul project (as it was first called) mobilized a larger student, alumni and community partner team with funding from the UW Population Health Initiative, the School of Public Health and the Department of Global Health.

The project provides blood-pressure screening kits and a team-developed health screening tool, designed to help women identify how they feel mentally and physically—including whether they feel safe and secure at home. The tool was a card with colors and images to indicate wellness (green), a warning to call a clinic (yellow) or an emergency requiring immediate care (red).

The feasibility study of Heart and Soul found widespread usage of the blood pressure cuff and screening tool. Chapman and the team used the feedback to enhance the tool, adding the piece that everyone affiliated with the project is excited about: The Joy Quotient.

It’s essentially a series of prompts to encourage study participants to think about what brings them happiness—from their five senses to the day’s events. The laminated card, in soothing tones of pink, purple and blue, lists gratitude and calming strategies. And it asks the reader to simply breathe:

“Breathe in, you are enough. Breathe out, you belong in this world.

“With every breath, remember you are full of life.”

This is missing from so much of traditional health care, explains Gilmore, who is also a midwife and naturopathic doctor. “So much of health care can be fear-based. But when you give someone tools, give them the ability to know when to seek help, when to fit in fear, you also can let them know it’s OK to have joy, to do small things for yourself.”

And so, as the post-pandemic, post-pilot iteration of Heart and Soul ramped up and became Heart, Soul and Joy, researchers provided more kits and monitoring tools for patients to use at home, while clinic partners resumed their roles as primarily in-person care providers.

* * *

During the feasibility study, when most perinatal visits were over telehealth, some providers reported that patients were calling in too often with concerns: a higher-than-normal blood pressure reading, for example. For time- and resource-strapped public health clinics, the calls underscored the need for patients to have clearer information.

Researchers considered the act of reporting itself a success: Patients were monitoring their health and taking the next step to call in. Still, the team expanded the health-screening tool, adding more information for midwives and other staff who were in the position of educating patients at the outset, helping them learn more about their own normal blood pressure levels, knowledge that can be lifesaving.

New mother Imani holds Zephaniah, whom midwife Nicola Solvay helped deliver in late September. Imani is one of about 100 new mothers and mothers-to-be enrolled in the Heart, Soul and Joy project to decrease maternal health disparities.

But researchers want clinics to change too. And that means adapting their health-care culture and boosting resources. During a typical 15-minute appointment, a pregnant person might relay any concerns since the last visit and be evaluated. If a translator is present, which allows for vital information to be communicated back and forth, patient to provider, provider to patient, then that allotted time essentially shrinks by half.

“They’re the people who are doing the hardest work with the fewest resources for the most vulnerable communities,” Chapman says of community clinics such as Neighborcare. “And yet they are partnering with us to find out how to do things better.”

Neighborcare Health, which primarily serves low-income and uninsured patients in the Seattle area, was a clinic partner in the Heart, Soul and Joy pilot during the pandemic and continues to enroll participants in the study at five locations. “The tool allowed for us to have a reminder to always screen for safety and well-being when, in the busy visits and the limited time we have, other needs can take priority,” says Nicola Solvay, co-director of Neighborcare Health’s midwifery program and practicing midwife at the Columbia City clinic.

The home-use blood pressure cuffs were a huge perk, Solvay says, recalling a patient whose blood-pressure readings at a clinic visit were normal, but were higher at home. So clinic staff ran some tests and learned that the woman had preeclampsia. “This diagnosis would not have been realized so early had we not had this program,” Solvay says.

She tells of another patient who disclosed thoughts of harming herself, something the woman came ready to discuss, thanks to the emotional health materials she’d been given as part of Heart, Soul and Joy. The appointment “turned into safety planning, and we were able to connect her, at that moment, with our behavioral health specialist down the hall,” Solvay recalls.

Two positive outcomes, in that patients identified and reported a problem, and clinic staff were able to respond immediately. But what of countless other pregnant people, and clinics, without even these tools? “My fear around the world of health care is that we mainly screen, and we don’t have the resources to do more,” Solvay says.

One tangible step, the researchers agree, could be increasing funding for public health clinics across the state so that medical staff have more time with each patient. Another, even more pointed step: Apple Health (Medicaid in Washington state) could cover blood pressure cuffs for every pregnant person enrolled.

“This project isn’t about further pathologizing people,” Harris says. “We’re saying to the systems, what can you do? What can you take away? What can you add to make sure people are healthy when they leave?”

* * *

Back at Neighborcare’s Rainier Beach clinic, Gilmore is enrolling her last new Heart, Soul and Joy participant of the day. She sits with a couple. The woman has just entered her second trimester, and one of the clinic’s midwives referred her to the project.

The husband translates Gilmore’s words for his wife in their native Soninke, a language spoken in The Gambia. From the tips on finding joy to how to use the blood-pressure cuff—wrapped around the upper arm, feet flat on the floor—he communicates and demonstrates all of it.

Gilmore then gives them the joy card and points to the examples of the five senses. “We talk about all the ways people can bring joy back into their lives so they’re not always living in a place of worry or fear and feel empowered,” Gilmore says. “For some people, thinking about the smell of their mother’s cooking brings them joy.”

The man translates, smiles. His wife looks at him, smiles, and they laugh together.