If Dance Professor Hannah Wiley could have one wish, it would be to stage a famous dance called The Green Table by Kurt Jooss, a German choreographer whose work blurred the line between ballet and modern dance. Jooss created his expressionistic work about the origins of war in 1932, in the face of the Nazi menace.

The Green Table is “a timeless anti-war piece” and “one of the best dances I’ve seen in my life,” adds Dance Program Director Betsy Cooper. Yet, it’s unlikely to be staged at the UW because Jooss’ daughter, who currently owns the rights, charges more than $100,000.

Compare that to the UW School of Drama, which pays as little as $375 for the right to do 10 performances of a play, and you can see why dancers are much less likely to get experience with the classics in their field.

Many of those classics are just too expensive—especially for educational institutions—and some are unavailable at any price. Unlike theater or music, in which works are published and anyone able to pay a standard fee can get a script or score and do with it whatever they like, dances often exist only on film or videotape, or in the minds and bodies of choreographers and dancers. That means that in addition to charging a fee, choreographers or their heirs can require that their representatives be present to ensure that a dance is done the way they want it done.

Which makes it difficult to give young dancers anything more than book learning or, at best, a videotape viewing, when it comes to historical dances, a situation Wiley calls “unacceptable.”

“A dance history course if useful, but it doesn’t help you know the work kinesthetically,” she says. “It’s reading about the work. I played the cello in the symphony when I was here as an undergraduate, and we got to play Brahms. We weren’t confined to reading about it.”

That’s why the creative core of the UW Dance Program’s Master of Fine Arts degree is the Chamber Dance Company—a group of graduate students that performs dances by well-known choreographers from Isadora Duncan to Mark Morris. Each year the CDC presents a concert that is entirely made up of these dances, often set by the choreographer or the choreographer’s representatives.

“This institution is entirely unique in that there’s this whopping great dance history experience that happens every single year,” Wiley says. “It’s living. It’s as if we all get to play the Brahms symphony instead of reading about it.”

Staging the concert has always been a challenge, as Wiley searches for important dances that are both available and affordable. The most logical starting point is the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, which has a large collection of dance information—including videos of many modern dances.

Then there’s the Dance Notation Bureau, where one can obtain the notated “score” of a dance for a fee, much as a musical score can be used for a fee. Notation systems meticulously reduce dance movements to symbols, but the process is time-consuming and expensive. As a result, only a fraction of all dances have been notated, and few in the dance world even read notation.

The UW Chamber Dance Company re-creates one of the Paul Taylor Dance Company’s signature works, “3 Epitaphs.”

Photo by Kozo.

Wiley taught herself to read it, but says she is hardly an expert. She has, on occasion, obtained scores to reconstruct a dance. More often, however, she has to go directly to choreographers or their heirs to obtain a dance, with widely varying results.

Sometimes a choreographer will immediately say yes and cite a reasonable price. Bill Evans, for example, only charged $450 for a 15-minute dance called For Betty. Betsy Fisher, who staged four dances by Mary Wigmann, a contemporary of Kurt Jooss, charged only $1,275.

Then there are dances like The Green Table. It’s expensive because the owner requires that two choreographers be in residence for five weeks and a third person for one week to “set the dance” on the CDC, and the UW must pay their expenses.

And money isn’t the only problem she faces in reconstructing dances. Choreographer Daniel Nagrin, for example, required that Wiley and the performers sign a contract promising not to talk to anyone about his dances. Some choreographers are simply reluctant to permit Wiley to have their dances at all. She asked Susan Marshall every year for eight years if she could stage a dance called Kiss before Marshall finally agreed. Lar Lubovitch said no to a CDC performance of North Star for at least as long before relenting when a dancer he knew joined the company.

Choreographers often refuse permission to do their dances out of fear “that their work will be out there and be done badly,” Susan Maguire says. Maguire ought to know something about it, since she is the director of the Paul Taylor School, Taylor2, and supervises reconstructions of Paul Taylor dances. She recently set his 3 Epitaphs on the CDC.

“I have mixed feelings about the situation,” she says. “I think yes if it’s going to be done before the public, then it has to be the best possible performance of that piece given the circumstances. But I wish there were a way for repertory to be made accessible to dancers who are in training for a very modest fee. I mean, how many times have we heard Beethoven played badly but it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t hurt Beethoven’s reputation.”

The UW has an advantage in convincing choreographers to grant permission to do their dances, however. The CDC is made up of professional dancers because the MFA program in dance is designed for professional dancers who are coming back to the academy after a performing career. Most are pursuing the degree in order to transition into education or some other post-performance endeavor, and the Chamber Dance Company puts their professional experience to good use.

Restaging the classics, Wiley says now, was in part a recruiting tool. “I thought that if we were going to create a grad program that would attract mature professional dancers, we had to somehow make it clear to them that their performances would be of master works,” she explained. “I didn’t want to ask them to come here and be in a Hannah Wiley dance.”

Once here, Wiley thought, the dancers would be able to give undergraduate dance students -indeed, anyone who came to the concerts – the gift of seeing historically significant dances. What she didn’t anticipate is how much the graduate students received from the experience.

“Many of these folks who come to the degree program may have danced with one or two major companies, so the work they have in their bodies is the work from that company,” she says. “It actually is transformative in some cases, where people have been locked into a certain vision through the eyes of their mentor, and the historical dances have served as a key to move them beyond it.”

Chamber Dance Company member Chris Kaufman recreates Doris Humphrey’s 1920 classic “Soaring.” Photo by Joel Levin.

Current Dance Director Cooper, who earned her MFA at the UW, came here certain that she wanted to pursue dance history as her teaching specialty—an interest that grew out of a childhood in New York City, where she had had the opportunity to see work by many of the major choreographers. Cooper was excited by the prospect of working with professional dancers like herself and deepening her knowledge of dance.

So when, after teaching elsewhere, Cooper applied for the UW director position, she proposed that a new course be created—called “The Creative Context.” The course, which she now teaches, uses the works being performed in the CDC’s yearly concert as the basis for an in-depth investigation of the socio-political, economic and aesthetic context in which the works were created. Students read and write about the choreographers, they attend a rehearsal and a performance of the concert and they have a conversation with the dancers.

The class introduces a whole new group of students to dance history in a very direct way. Although undergraduate dance majors have always been welcome at CDC rehearsals, most of the Creative Context students are not dancers, Cooper says.

“They often tell me in the beginning that they don’t understand modern dance, that they feel dumb,” she said. “They feel like there’s a message there and they’re not getting it. So we spend 10 weeks demystifying this thing. They learn there might be a message, there might be lots of messages, there might be no message, they’re not dumb.”

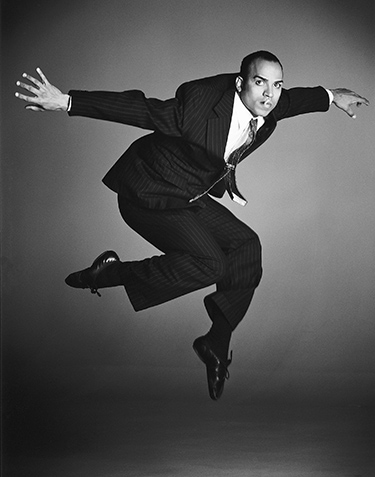

Chamber Dance Company member Hector Vegas recreates Daniel Nagrin’s 1948 solo “Strange Hero.” Photo by Joel Levin

Watching the dances in the studio—where the dancers are in rehearsal clothes and about two yards from those watching—teaches something else, Wiley says. “You hear the breathing, you get the sweat, you see how hard it is. Then I talk to the audience a little bit. Then a couple of weeks later, these same people go to the concert where they can’t hear the breathing, they can’t see the sweat, but they see the totality of it. It’s adding those two experiences together that’s a treat beyond belief. There’s a depth that the people who come to both get to experience that is close to dancing it.”

The CDC has been performing historical dances at the UW for 15 years, and in that time the dance world has begun to pay more attention to the preservation of such dances. The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts has, for example, created the Collaborative Editing Project to Document Dance, which pairs choreographers with videographers to work on recording significant dances in such a way that they can be easily reconstructed.

And the American Dance Legacy Institute at Brown University is tackling the problem of accessibility by inviting choreographers to create “repertory etudes”—short dances based on their signature works. These dances are videotaped and can be obtained by anyone for a modest fee. Each etude package includes a videotape of the dance, including instructional and coaching footage; a CD of the music; a notated score; costume and lighting suggestions; and a resource guide with additional information, such as historical notes, bibliography or improvisational exercises.

None of this will prevent choreographers or their heirs from holding tight to dances or charging high fees for reconstruction, but the recent case of Martha Graham—who died in 1991—should lead them to think about their legacy. The Martha Graham Company was unable to perform her dances for two years because of a disagreement between her heir, Ronald Protas, and the company’s parent organization, the Martha Graham Center for Contemporary Dance, over who owned the dances.

After a lengthy court battle that ended this fall, the center won. The judge ruled that when Graham sold her school in 1956 to a nonprofit foundation, she forfeited ownership of her work in exchange for a regular salary and thus became an “employee for hire.”

No choreographer wants to lose control of his or her work; yet, is it more important to hand the dances down to someone who will make sure they are performed “correctly” for a fee or to make sure the work continues to be performed widely? While acknowledging that choreographers should receive fair compensation for their creations, Wiley and Cooper argue that important dances should be as available as possible for reinterpretation by new generations of dancers.

“Performing a dance is getting to know it in a way that you could look at it 100 times and never know it in that particular way,” Wiley says. “So in their years here CDC members might perform in eight or nine historical figures’ work and that’s a deep, deep insight into history.”

“Dances change every time they’re performed anyway,” Cooper adds. “Even classical ballets like Swan Lake that have supposedly been handed down intact look very different today than when they were created.”

Cooper thinks the dances have value to non-dancers too. “We were studying German expressionism in the Creative Context class one year because the CDC was performing work from that period,” she says. “One of the most gratifying pieces of feedback I ever got was when a student told me she had learned so much about the Holocaust and the rise of the Nazis in that class. I tell them we’re not just studying dance history; we’re looking at human history through the lens of dance.”