Comeback trail Comeback trail Comeback trail

One athlete journeys from injury to recovery with the help of sports medicine experts at the UW.

One athlete journeys from injury to recovery with the help of sports medicine experts at the UW.

Ella May Powell was running drills with her teammates when something popped in her left knee—a different sensation than any injury she’d experienced before. Panic set in.

It was early in the fall of 2020, and the UW volleyball setter had been practicing with her teammates. The familiar thuds of volleyballs and squeaks of shoes echoed throughout the otherwise empty Alaska Airlines Arena.

The team hadn’t practiced much over the spring and summer because of the COVID-19 pandemic and they were thrilled to finally be back on the court together. In Powell’s freshman season, the Huskies had made it to the Sweet Sixteen round of the NCAA tournament. In her sophomore year, they advanced to the Elite Eight. Powell, at the time a junior and one of the best setters in the country, had high hopes for the season ahead.

But on a routine play that day, she backpedaled and twisted to her right to set the ball for a teammate and then came the alarming pop. She hopped awkwardly to the side of the court, tried to take a couple of steps and then sat down, stunned. Tears welled in her eyes. Jennifer Stueckle, the team’s athletic trainer, rushed to her side.

After having knee surgery, Ella May Powell works on her recovery and rehabilitation with the help of Jennifer Stueckle, an associate athletic trainer.

“I wasn’t crying because it hurt,” says Powell. “I was terrified because I knew something was wrong.” An MRI would confirm her worst fears: She had torn her medial meniscus. It would require surgery, and she wasn’t sure when she would play again.

Luckily for Powell, her treatment and recovery were in the hands of a tight-knit team—including UW Medicine’s Dr. John O’Kane, UW Athletics medical director and head team physician; Dr. Mia Hagen, UW Athletics team physician, orthopedic surgeon and surgical director of UW Medicine’s Sports Medicine Center at Husky Stadium; and Stueckle, an associate athletic trainer for volleyball and beach volleyball.

As a field, sports medicine focuses on treating activity-related injuries. And the Seattle area—with one of the most physically active populations in the U.S.—boasts a wealth of resources for those seeking treatment. Among them is the Sports Medicine Center at Husky Stadium, which benefits from what O’Kane calls a triple threat of clinicians: those who serve patients, teach at the UW School of Medicine, and do research to keep athletes safe and healthy—now, and far beyond any amateur or professional career they may have.

UW Medicine’s sports medicine team serves people of all ages and abilities at several locations around Seattle, but UW athletes are most familiar with the Sports Medicine Center, a 30,000-square-foot facility that opened in 2013. Some of the staff also work as team physicians for the Huskies, Seattle Seahawks, OL Reign (the city’s professional women’s soccer club) and Seattle Seawolves (Seattle’s professional men’s rugby team), as well as the Seattle Marathon and several public high schools. The center and its staff also serve tens of thousands of members of the community every year.

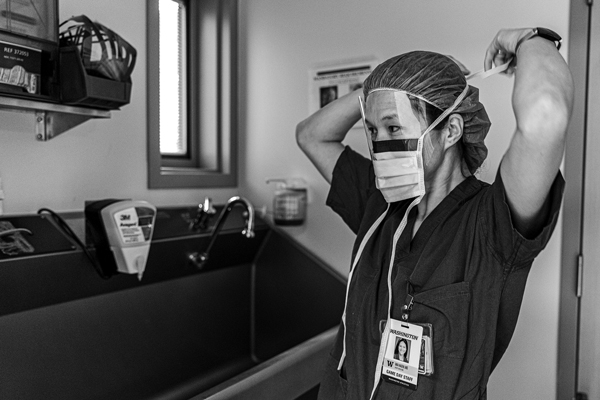

Dr. Mia Hagen preps for surgery on an injured athlete. Her patients include students, professional athletes and weekend warriors.

* * *

O’Kane came to the UW in 1993 for his medical residency, followed by a fellowship. He is now a UW School of Medicine professor and head team physician for the Huskies. He says one of the center’s strengths is its location in Husky Stadium. “We have a world-class medical center literally across the street,” he says, referring to UW Medical Center’s Montlake location. “We have top-quality X-ray, ultrasound and MRI. It doesn’t matter what you need medically. It’s right here because of that co-location.”

Another of the sports center’s strengths, says O’Kane, is how the hospital extends into the training room—every day, a sports medicine physician visits the training room, which is connected to Alaska Airlines Arena and Husky Stadium by hallways and tunnels. After her injury, Powell was evaluated by the on-call physician. A few days later, she returned for an MRI.

Surgeon Mia Hagen consulted with Powell next. She diagnosed a bucket-handle tear in Powell’s meniscus, the cartilage that absorbs shock and helps stabilize the knee. It had torn, flipped over—like a handle on a bucket—and lodged in her joint. Hagen had seen this type of injury before. It typically happens when athletes twist their knees, and because the meniscus gets stuck where it shouldn’t be, it results in swelling and instability, and limits mobility. It rarely gets better without surgery.

Hagen presented two options. The faster fix would involve removing the torn part of the meniscus, which would require a four- to six-week recovery. “But it’s a trade-off,” says Hagen. “It’s a structure that your knee needs, so without an intact or repaired meniscus you could be more likely to develop cartilage damage and arthritis in your knee in the long run.”

The second option would be to repair the meniscus—flipping it back and sewing it into place—giving Powell the best chance of long-term knee health. It would, however, mean a four- to six-month recovery process. Powell, who hopes to play professional volleyball overseas and for the U.S. national team, opted for the latter surgery despite the longer recovery time. “It was the correct choice in my opinion,” says Hagen.

An MRI does not paint the whole picture, though, and Hagen wouldn’t know which option would be the most successful until she could view the inside of Powell’s knee during surgery. And, of course, Powell wouldn’t know her recovery timeline until after the operation.

“I went into the surgery a mess,” says Powell. “Dr. Hagen told me that if I woke up with a knee brace on, it means it was a repair. If I woke up without a brace, it was the quick surgery.” Powell woke up with a knee brace on. She had a long road ahead.

With Jennifer Stueckle’s help, Powell balances on a BOSU ball to strengthen her knee and other leg muscles.

* * *

When Powell plays, she does it all: serving (she holds the Husky record for career aces), diving for digs, setting up her teammates for kills and dropping in deceptive dump shots. It’s hard to imagine her not on her feet. It was far harder for her to work through it.

For six weeks following surgery, she was on crutches and in a brace. Stueckle, the team’s athletic trainer, developed a program of non-weight-bearing exercises to keep Powell’s upper body in shape and build a foundation for the rehabilitation of her knee—including stretching her leg muscles and increasing her knee’s range of motion, and setting a volleyball while sitting on a box. And then, when Powell was able to start putting weight on her leg, Stueckle introduced new, challenging exercises, like standing on an unstable surface with her left leg and working on her sets.

“I had lost a ton of muscle in my quad, calf and hamstring. So the silliest little exercises like leg raises would absolutely gas me. It was a lot of lonely work,” Powell says. But she wasn’t truly alone. Every day before practice, and often multiple times a day, she would meet with Stueckle for her ever-evolving rehabilitation. She also had periodic check-ins with O’Kane and Hagen, who confirmed her knee was improving as expected.

When a resurgence of COVID-19 pushed the 2020 season to January 2021 and the NCAA granted athletes an extra year of eligibility, Powell had renewed hope and a clear recovery target. Still, she endured her share of low moments, including recurring pain in her knee due to a suture. Hagen had O’Kane evaluate the area using ultrasound and inject it with a steroid to decrease inflammation, which solved the problem. Later, Powell went through a two-week slump in which she didn’t feel like she was making any progress, but Stueckle continued to reassure her that she was on the right path. “A big aspect of rehab is educating and collaborating with my athletes,” Stueckle says. “A lot of it is, first and foremost, having that relationship with athletes, building that trust.”

“Jenn has been there with me since day one,” says Powell, who, like the rest of the team, has seen Stueckle in the training room for preventive maintenance and minor injuries since she was a freshman. “She did such a great job handling both the physical and emotional side of my recovery.”

When Powell returned home to Arkansas for winter break in 2020, Stueckle provided her and her personal trainer with a rehab program. And in January, when Powell was back in Seattle, Hagen had her run through a litany of tests and a thorough knee exam—and told her she was physically ready to play. It was just up to Powell to decide if she was mentally ready.

For athletes, the mental hurdle in recovering from an injury is often the hardest, says Hagen. UW Medicine doctors sometimes refer athletes to team psychologists, who help them process everything from the academic and personal struggles to intense pressure and career-ending injuries. That holistic care wasn’t always the case, says O’Kane, speaking of sports medicine practices in general, not specifically at the UW. “It used to be a race to see how fast surgeons could get athletes back out there after injuries like ACL tears.”

In the early 2000s, UW Athletics formalized a partnership with UW Medicine to provide team physician services. To avoid any potential conflict of interest, says O’Kane, the doctors have the final say in whether an athlete is ready to play: “It’s written into our contract.” Today, this type of autonomous health care is a guiding NCAA principle, and while some institutions have found it challenging to achieve, it’s fundamental to the relationship between UW Athletics and UW Medicine.

In her final season, Powell reached 162 career aces, setting a school record and prompting the Seattle Times to call her “the Queen of Aces.”

“Coaches and players are often the gas, and we’re the brakes,” O’Kane says. “They’re the ones who are pushing a little bit, and we’re the ones who are holding back a little bit. It’s a really tight connection at the UW, but the final say about ‘play, not play,’ is with the physician.”

Fortunately for Powell, her recovery had gone smoothly, and Hagen and O’Kane’s reassurance was all she needed mentally. “We don’t see a reason to hold you back,” Hagen told Powell in that final appointment. Powell didn’t either.

Over the next few months, she helped lead the Huskies to a conference championship and to the Final Four for the first time since 2013. “Ella May went from sitting on a box in the fall to first-team All-American in the spring,” Stueckle says.

But Powell wasn’t done. Just months later, she and the Huskies were back again, winning their second-straight Pac-12 title and advancing to the Sweet Sixteen. Powell was named Pac-12 setter of the year both seasons, cementing her spot as a Husky great.

While O’Kane and his team see more than 700 student-athletes for their primary-care needs, and Hagen’s team treats them for musculoskeletal injuries, that’s just part of their caseloads. The rest are patients from the community. (Other specialists at the center, including physiatrists and physical therapists, also treat UW athletes and community patients alike. And a number of UW sports medicine clinics in the greater Seattle area extends that community reach even further.)

UW Medicine as a research powerhouse applies just as much to someone like Powell as it does to anyone else. “There’s nothing about Ella May that resembles most of the other people in the world,” says O’Kane. “But the way you approach her is carried over to the way that you approach other folks.”

Those other folks could include a young soccer player or a senior who hikes. And regardless of who the patient is, the same tools are available, from technologically advanced surgery to nonsurgical treatments like ultrasound-guided procedures, nerve pain reduction techniques and platelet-rich plasma injections to help inflamed tendons and joints. Whether the treatments and technologies are new or have been used for decades, UW Medicine relies on its wealth of research and expertise to ensure they remain safe and effective.

In 2015, Dr. John Drezner, a UW Athletics team physician and director of the UW Medicine Center for Sports Cardiology, was a leader in a Seattle meeting of international experts who used new research to standardize the interpretation of electrocardiograms in athletes. Known as the “Seattle criteria,” it is today used by doctors around the world to improve the screening of amateur and professional athletes and identify potentially life-threatening cardiovascular abnormalities before they strike on the court or on the field. “There is a lot of community trickle-down from UW Medicine’s research,” says O’Kane.

Dr. John O’Kane examines a student-athlete’s knee.

* * *

Powell’s senior season ended on Dec. 2 in an NCAA tournament loss to Texas Christian University. While she now faces the challenge of leaving behind a team and university that has shaped her over the past five years, she looks forward to her future—including volleyball (hopefully for a pro team in Italy, she says) and a career in sports journalism. And though Powell’s teammates and coaches will miss her, her five years of leadership left a lasting impression and nurtured rising stars on a Husky team that has made it to the NCAA tournament for 21 straight years.

When Powell reflects on her UW career, her team’s and her own accomplishments are undoubtedly the high points, but she can’t fully separate them from the many months she spent recovering from her knee injury with the help of O’Kane, Hagen, Stueckle and others.

“I have nothing but gratitude,” she says. “They have trained me to take care of my body going forward. I won’t get the care anywhere else that I did here.”