In 1990, when the UW recommended placing its new Tacoma campus across the street from the old railroad station on Pacific Avenue, some politicians and editorialists said it a mistake. "The area was fairly dangerous after 6 p.m.," UWT Professor Ron Butchart recalls. "It was gloomy and run down. Most of the buildings were essentially abandoned. It was an incredibly depressed area."

“It was a low-end warehouse district. One building was packed with parts for World War II era Jeeps,” adds Branch Campus Projects Director Joe Brawley. One empty building was home to hundreds of pigeons. Another’s roof was so leaky it rotted. “There was nobody there. It was not even a red light district,” Brawley recalls.

Today, University of Washington Tacoma Dean Vicky Carwein can rightfully exclaim, “The siting was absolutely brilliant. We are in the heart of downtown Tacoma. We will become a national model of what an urban, downtown, commuter campus can be in–and to–its community.”

The UW could have built a new campus away from Tacoma’s downtown or it might have torn down what were century-old eyesores for a “modern” campus of concrete and glass.

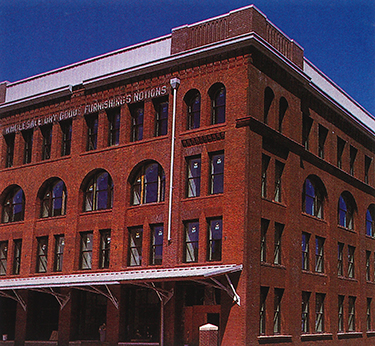

Century-old brick warehouses along Pacific Avenue are now part of the UWT’s academic complex.

Instead, six historic brick structures have been gutted, upgraded to withstand major earthquakes, and wired for 21st century technology.

When its doors open on Sept. 29, UWT will have room for about 1,200 full-time students in a $33 million campus. Architects organized the site around a central plaza, featuring an academic complex born of four old warehouses, a brick storehouse turned into a computer lab and a library with a reading room that once served as a power station.

“What we have done is take 19th century warehouses and turn them into 21st century academic space,” explains Brawley. It’s what architects call adaptive reuse, not preservation. Much of the credit can go to the late, award-winning architect Charles Moore, who also designed the new Chemistry Building on the Seattle campus. He had the vision to remake the district into a model urban campus.

A century ago, these buildings were part of Tacoma’s rise on the bluffs above Commencement Bay. When the Northern Pacific Railroad crossed over Stampede Pass in 1886, a frenzied building boom erupted in the City of Destiny. These brick warehouses were built between 1890 and 1911, some to house canned goods and other groceries, others as general storage facilities.

A photo from the 1920s shows the original use of one campus building: commercial storage.

Butchart calls the architecture “muscular” with touches of Classical and Romanesque influences. “There was a good deal more attention paid to civic aesthetics back then,” he says.

The most striking building is the 1902 Snoqualmie Falls Power Station, which is now the library’s reading room. “It is the jewel of the campus,” Butchart declares. With its Classical Greek influences, its soaring two-story space and rows of arched windows, the old power station has the feel of an academic building. “It reminds me of Jefferson’s ideal of what an academic building should look like,” he says.

Inside there is a mix of Classical and high tech. Students in the reading room can look up at a gantry for a traveling crane, installed 100 years ago to take transformers in and out of the power station. Rather than tear it out, architects left it as an artifact of the building’s–and Tacoma’s–history.

In fact, much of the old has been preserved within the new. Instead of sandblasting bricks to make them look new, the UW is leaving them with a patina of age, old paint and pollution. In many places, old wood beams are exposed, the ancient skeleton of the warehouses.

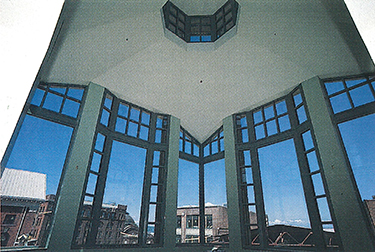

There are some new pieces to the campus as well. Attached to the reading room is a new wing for the library’s circulation department, periodicals and some book stacks. Workers replaced a blank wall on the computer lab building with a new façade featuring banks of windows that overlook the campus plaza.

The view from the library’s tower includes campus buildings and the dome of the recently restored Union Station.

“The plaza should become the public gathering space,” says Butchart. Unlike Seattle’s “Red Square,” this plaza will have grass, trees and shrubs when it’s completed. Someday the plaza will be the starting point for a “grand staircase” that will climb the hill as the campus expands.

Other new touches include two atria–one at each end of the academic buildings. Dank warehouse rooms are now open offices, meeting spaces and classrooms, most with plenty of natural light. New elevators and ramps ensure that 100-year-old buildings provide modern access to all students.

Another new twist is that the University is now a Tacoma landlord. The Pacific Avenue side of campus has ground-floor space for retailers. Among the first tenants are the University Book Store, Starbucks, Subway and Taco del Mar.

“Pacific Avenue could be as dead as a tomb,” warns Brawley. But with the UWT campus, the federal courthouse and the Washington State History Museum lining Pacific, retail activity should flourish. “We’re going to see all the retail space fill up in a year or so,” says Butchart. “It is already transforming the district.”

The red brick facade of one warehouse shows off its “muscular” architecture.

Renting out retail space is symbolic of the UWT mission–not being an ivory tower enclave, but serving as a vital part of the community as it educates “placebound” students at the junior, senior and graduate levels.

Since UWT opened its doors in rented quarters in 1990, “We are absolutely meeting this mission,” says Dean Carwein. The average age of the UWT student is 32, and a majority of the students work as well as attend classes.

The campus has already met its enrollment targets. “When we move, we will be 200 students over capacity,” warns Carwein. “We may have faculty in temporary offices the day we move in.”

Even though these are heady days for UWT, Carwein is not shy about the future. By 2011, there could be 9,300 full-time students at the campus. In the next 25 years, Carwein sees the campus growing up the hill to fill its planned 46-acre site.

One hundred years from now she see a campus of 20,000 students with dormitories and Ph.D. programs. “It will be a four-year institution with a statewide draw, a truly full-service university with some active research programs.”

As part of its philosophy of adaptive reuse, the UW rebuilt an awning that once protected warehouse workers as they unloaded boxcars. Now the awning will protect students as they go between classes. Also note the faded paint at the top of building, advertising its original use.

City officials are overjoyed with the project. “It will not be displacing or destroying the past. It will be respectful of it,” Michael Sullivan, Tacoma’s cultural resources manager, told the press when the project began. Bringing a world-class university to the area can only help in Tacoma’s rebirth. “Access to a state university hasn’t been real easy for us here,” Sullivan noted.

It’s a giant step for a once-sleeping giant. “Tacoma used to be a place you went through on your way to someplace else,” says Butchart, who once lived in Seattle but now calls Tacoma home. He confesses that he was more interested in teaching at UW Bothell than at UW Tacoma when both campuses opened. But a one-day visit to Tacoma changed his mind. “It’s a gritty place that has decided it won’t become another Oakland,” he says.

He sees Tacoma as again the city of destiny. “The naysayers are going to have a hard time 10 years from now.”

A time of sharing: UW Bothell will grow alongside a new community college

The birth of the new millennium will also see the birth of two campuses at one site along the I-405 corridor–the University of Washington Bothell and Cascadia Community College.

Last April, the state Legislature set aside $91 million to design and build facilities near the intersection of I-405 and State Route 522 in Bothell. The new site may open in the fall of 2001, serving about 1,200 UWB students and about 800 community college students.

Legislators were reluctant to build two new campuses in the area, instead directing the institutions to “co-locate” at one central place. According to a master plan, the funds should cover construction of three buildings: one would mostly serve UWB, one would mostly serve the community college, and one would have common places such as a library or student services.

It is too early to tell what the structures will look like, but it is safe to assume they will be a far cry from the 1890s brick warehouses that hold the new UWT campus.

But in many aspects, the two campuses have a lot in common. Like UWT Dean Vicki Carwein, UWB Dean Norman Rose is worried that his campus will be full the moment his students move in. “We have more than 1,000 students right now,” he says.

Rose says there has been remarkable growth at Bothell the last two years, and with the addition of a computer science and engineering degree program next fall, more students are coming.