In the early 1980s, Freeman came to a crossroads. She realized that to truly advocate for snow leopards, she had to move beyond the zoo. With encouragement from her family—and a healthy list of pros and cons scribbled at the kitchen table—she took the leap and founded the Snow Leopard Trust, a conservation organization grounded in science, education and community partnerships. It was a bold move, especially for a woman navigating male-dominated fields and complex international politics. But Freeman was unstoppable.

She traveled the world, particularly to Central and South Asia, forging relationships with local communities, researchers and governments. At home, she coped with chronic bronchiectasis—a lung condition she developed in childhood—but she rarely slowed down.

“She would come home exhausted, sit on the back porch and talk it through with my dad over martinis,” says Harry Freeman. “But she always kept going.”

Today, the Snow Leopard Trust operates in 12 countries, supporting more than 150 Indigenous and local communities and advancing some of the most respected field science in conservation. Its leadership is global, its reach growing. Freeman’s vision of protecting snow leopards in the wild—not just in zoos—has become reality.

Back at Woodland Park Zoo, the work Freeman and her colleagues had started continued. In the 1990s, conservation biologist Lisa Dabek, ’91, ’94, followed in their footsteps. A UW graduate student interested in animal behavior, she was drawn to an equally mysterious species: the Matschie’s tree kangaroo of Papua New Guinea. These cinnamon-colored marsupials, dubbed “ghosts of the rainforest,” had never been studied in the wild. Their fur blends with the mossy canopy, hiding them from both predators and people.

-

-

Lisa Dabek’s work, inspired by Helen Freeman, is why tree kangaroos can be seen thoughout the zoo’s Forests for All exhibit. Photo by Jonathan Byers.

-

-

Dabek was drawn to the cute yet mysterious Matschie’s tree kangaroo of Papua New Guinea. Photo by Jonathan Byers.

Dabek focused her thesis on their behavior and bonded with the animals at the zoo—mothers with joeys in their pouches. Mentored and inspired by Freeman, Dabek launched the Tree Kangaroo Conservation Program, partnering with communities in Papua New Guinea. “I felt I could champion this little-known animal,” she says. She didn’t want to stop the hunting or cultural use of tree kangaroos, she says. “But I wanted to make sure there would always be healthy populations.”

The approach was the same: collaboration, not control. Today, the program trains former hunters as trackers, engages villages in forest protection and uses remote cameras to study the elusive animals.

A new chapter is unfolding at the Woodland Park Zoo with the construction of Forests for All, an immersive habitat that re-creates the tree kangaroos’ arboreal world. Thirty-foot-high netted enclosures, live trees and viewing areas will let visitors experience life in the canopy—echoing Freeman’s philosophy of empathy through experience.

“She was a force of nature,” Dabek says of her mentor. “Feisty, funny, brilliant. She filled my mind with ideas.”

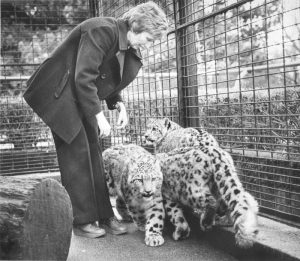

Though Helen Freeman died in 2007, her legacy lives on—not only in thriving conservation programs, but in the way zoos around the world now approach the care and study of wildlife. Her life’s work continues to move outward—from the windy heights of the Himalayas to the cloud forests of Papua New Guinea and the shaded paths of Woodland Park Zoo. A life-sized bronze snow leopard sculpture stands at the zoo in Freeman’s honor, along with a plaque and a replica of her clipboard etched with field notes.

“As the late Helen Freeman left behind a legacy to save snow leopards in the wild, our Helen has also left her own legacy and gave us a peek into the world of snow leopard moms successfully raising cubs and teaching instinctual skills,” said Beth Carlyle Askew, animal care manager at Woodland Park Zoo.

Helen, the snow leopard named in Freeman’s honor, died this spring at age 20. Over her long life, she became a matriarch in the zoo’s conservation breeding program. Her descendants still roam the zoo enclosures designed with Freeman’s ethos in mind—spaces that honor the animals’ wild instincts, dignity and need for rugged terrain. In keeping with Freeman’s belief that the animals should teach, the zoo donated the snow leopard’s remains to the Burke Museum. Her bones are now part of the research collection where they will continue to educate students, scientists and the public.

What began as two frightened animals in a cold enclosure became a global movement.

“Helen was always 10 steps ahead,” says Marissa Niranjan, deputy director of the Snow Leopard Trust and a UW alum. “She believed that science and community could work hand-in-hand—and that you could have a safer population of snow leopards and support healthy communities.”

Thanks to Helen Freeman’s vision, the zoo was one of the first in the country to embrace the full spectrum of conservation: captive breeding, habitat immersion, field research and community-led preservation.

The Snow Leopard Trust, too, has become a beacon of what conservation can be: science-based, community-rooted and culturally aware. With scientists, conservationists and educators working in places including Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, India and Mongolia, it protects not just a species, but a way of coexisting with the wild.

Tree kangaroos now populate through the Forests for All exhibit, and schoolchildren will soon look up in awe, hoping to glimpse the cinnamon-colored ghosts of the canopy. Dabek’s fieldwork is entering a new phase—non-invasive tracking, long-term community partnerships and forest preservation. The children of hunters are now becoming trackers and conservationists. The forests are not empty; they are watching, breathing, rebounding.

Freeman once wrote that “zoos have the power not just to display the wild, but to teach people how to love it.” That lesson endures, whispered in the puffing call of a snow leopard or the rustle of leaves as a tree kangaroo slips across the canopy.