As much as being a black cook aboard a slave ship changes Middle Passage protagonist Rutherford Calhoun, his creator, UW English Professor Charles Johnson, is holding steady through the months of accolades that have followed winning the 1990 National Book Award in fiction.

Since accepting the prestigious award for his fifth book, Johnson has been hurled and twirled around the nation for interviews, writing workshops and autographs. His phone rings with project offers and pleas for endorsements from newer authors. Just when demand might have died down, February’s black history celebration and Middle Passage’s climb to the best-sellers list kept his schedule and suitcase packed. Johnson has been the subject of pieces in the New York Times, the Washington Post, NBC’s “Today” show, and People magazine. Syndicated columnist George F. Will even devoted an entire column to the work.

Johnson’s two children are accustomed to the writing-and-drawing life, so having dad publish another book is nothing new, he says. What is new for Johnson and his family is the steady stream of public attention; the newly lost ability to go anonymously to the shopping mall.

“People come up to me all the time now,” he says. “They’ve seen my picture in the paper, read my book, and want to congratulate me. It has happened in New York as well as in Seattle.”

Established in 1950, the National Book Award for fiction has gone to a galaxy of American writers, such as Katherine Anne Porter, Thomas Pynchon, William Styron, John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates, Thornton Wilder, Alice Walker and Wallace Stegner. One award winner, Saul Bellow, went on to win a Nobel Prize in Literature.

“I've learned to get my work done without external recognition. If I had won the award early in my career, I may not have learned how to do that.”

Charles Johnson

This was a good year for Johnson to join their ranks. The 15-year veteran of the UW English department is on sabbatical and available to respond to the extensive nationwide media attention he’s received. After three years as director of the department’s Creative Writing Program, Johnson will begin, in October, his five-year term as the first S. Wilson and Grace M. Pollock Professor in Creative Writing. It is the first endowed professorship in creative writing in the University’s history.

The timing also was right because Johnson feels psychologically and professionally mature enough to take the hoopla in stride.

“I couldn’t have handled all this in my 30s,” says 42-year-old Johnson. Then, with the faint and knowing smile of an author who has labored in obscurity, he adds: “Well, maybe it would have been OK if I’d won it in my 30s, but not in my 20s. I was too young in my 20s.

“Winning an award like this and being sought after for interviews and endorsements would send a younger writer bouncing off the walls,” Johnson says. “I’ve been publishing since 1965. For 20 years I have been self-generating. I’ve learned to get my work done without external recognition. If I had won the award early in my career, I may not have learned how to do that.”

Johnson endured plenty of bumps on his road to success. He wrote six novels before his first published book, Faith and the Good Thing, was released in 1974. His next work, Oxherding Tale, was rejected by 20 publishers and did not appear until 1982.

He is a Guggenheim Fellow, winner of a Writer’s Guild Award for the PBS drama “Booker” (a look at the childhood of Booker T. Washington), and one of the best short story writers in America according to a University of Southern California survey. He is a regular book reviewer for the Los Angeles Times; and, in 1988, was a judge for the National Book Awards, the year Pete Dexter won for Paris Trout.

“I know who I am today, and not a lot about my life or my work is going to change at this point,” he says. Johnson tags that remark with references to the anchors in his life: his 22-year marriage to wife Joan, to whom Middle Passage is dedicated; his two children, Malik, 15, and Elizabeth, 9; and 15 years teaching creative writing at the UW.

These are the kind of anchors Middle Passage’s irresponsible protagonist, Rutherford Calhoun, didn’t even know he was searching for. Calhoun and Johnson, however, are not totally disparate characters. Both are well-educated black men from Illinois who pepper their lives and conversation with a steady, but understated, humor. They know how to get along, and they know how to fight.

These are the kind of anchors Middle Passage’s irresponsible protagonist, Rutherford Calhoun, didn’t even know he was searching for. Calhoun and Johnson, however, are not totally disparate characters. Both are well-educated black men from Illinois who pepper their lives and conversation with a steady, but understated, humor. They know how to get along, and they know how to fight.

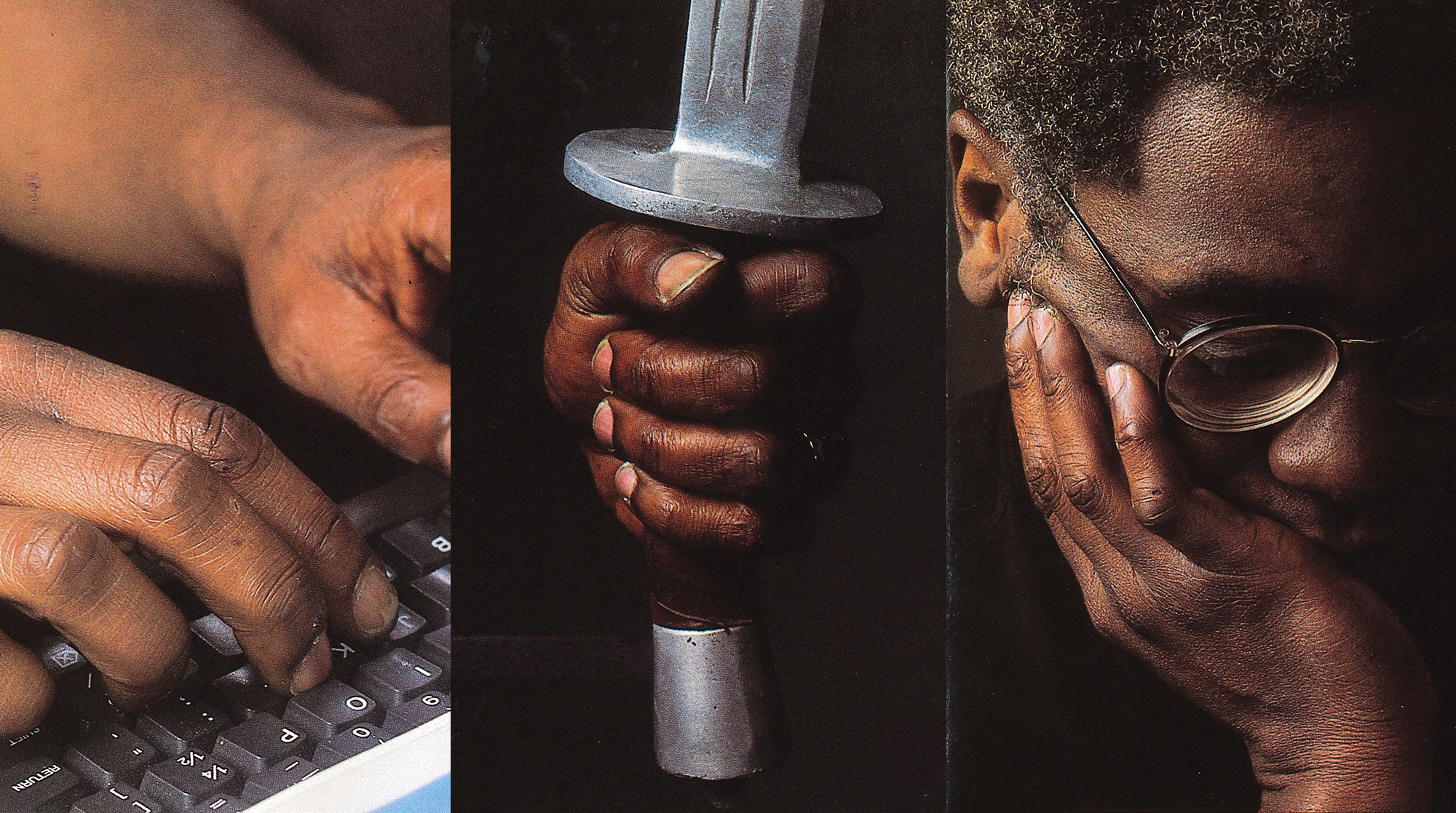

In 1830, Calhoun, a freed slave, unknowingly stows away on the Republic, a slave ship, crewed by a gang of white misfits, where “death climbed in through every portal.”

Today, Johnson navigates the sometimes rough—and predominantly white—waters of American academic and literary circles where recognized black intellectuals are still an anomaly. The last time a male black American won the National Book Award was in 1953 when Ralph Ellison was honored for Invisible Man.

When Ellison won that year, Johnson was a child living in an integrated neighborhood in Evanston, Ill. The only son of a night-watchman father and an artistic mother, Johnson’s home was filled with books and music. His creativity was fed and encouraged. He began writing a journal at age 12 and found a knack for cartooning that led, in 1970, to the PBS series “Charlie’s Pad,” about drawing cartoons.

Still interested in cartooning today, Johnson’s avocations also include Zen Buddhism and the martial arts. (He’s an instructor for Seattle’s Phinney Ridge Neighborhood Center.) He holds both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Ill., but never completed his doctoral studies at the State University of New York-Stony Brook.

Neither Johnson nor Calhoun set out to be unique; their abilities, interests and character took them where they would. Calhoun describes such a life this way: “The voyage had irreversibly changed my seeing, made of me a cultural mongrel, and transformed the world into a fleeting shadow play I felt no need to possess or dominate, only appreciate in the ever extended present.”

In spite of some similarities, Johnson is not Calhoun. Their differences are sharp. Johnson is reliable and consistent; Calhoun unpredictable and selfish. Johnson rests in his marriage and family; Calhoun runs from commitment.

Calhoun has a bitter taste in his mouth for “Da,” the father who abandoned him as a child— the father who couldn’t put his family above himself. This figure is in sharp contrast to both Johnson as a parent and Johnson’s own father, who worked three jobs to provide for his wife and son.

But Da gives Johnson a chance to describe a path that, in Johnson’s view, leads nowhere. “Afterward he’d bring stump whiskey to whomever he’d whooped, saying he was sorry for all the bed-swerving and scrapping and gambling he did—that he couldn’t help it, and besides, it wasn’t really his fault he acted that-away, was it? ‘Looka how we livin’,’ he’d say. ‘Looka what they done to us.’ You couldn’t rightly blame a colored man for acting like a child, could you?”

While race plays a central role in the novel, Middle Passage is a morality play from a human, not black, perspective. Page after page it points out, then shatters, stereotypes. Johnson makes sure all the characters in Middle Passage escape confinement in labeled boxes.

For example, not all slave owners are without merit. It is Calhoun’s white owner who sees that he is educated and eventually freed. And it is a black, mistaking power and property for freedom, who helps the slave trade prosper. The ship captain and shipmates are slaves to their economic plights and moral shortcomings, while members of the African Allmuseri tribe, crossing the Atlantic as cargo, are free. The depth of his characters and complexity of the story reflect Johnson’s six years of research and writing. He puts flesh on our skeletal knowledge of the slave trade.

Johnson knows the pain as well as pride in being described as a good black writer. Johnson is a good writer. He is black. Is that the same as being a good black writer? Would he still be a good writer—the same writer—if he were white?

Johnson’s voice is his own. His images, sometimes garish, sometimes filled with the charm of understated humor, are his. He knows what it is to be black and can articulate it. But he does not speak for his race or want to be bound by it.

“What is a black writer?” he asks. “Take five black writers and you have five different styles; even in describing the same incident, each brings his own perspective. There is no such thing as black writing any more than there is white writing. My topics might be different if I were not black, but my style would be the same.”

Neither Johnson nor Calhoun nor the book are to be stereotyped. Life in the Middle Passage just isn’t that simple. It is about people, some black, some white, dealing with the circumstances of their lives, as Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed, “according to the content of their character, not the color of their skin.”

It’s a fitting introduction to Johnson’s next novel: a story about a Martin Luther King Jr. double, and what happens to him after King’s assassination.

The UW ‘s Creative Writing Program, which Johnson led for three years, is a hub for literature in the Pacific Northwest. It is now directed by David Bosworth, whose first book, The Death of Descartes, won the Drue Heinz Prize in 1981 and his most recent novel, From My Father, Singing, won the Editor’s Book Award.

Each of the 10-member fiction and poetry faculty has won awards for their published work. The literary power packed into the program has made it one of the most competitive offerings in the College of Arts and Sciences. Approximately 55 M.F.A. students enroll each year to train for professional writing and teaching careers. In 1987, the program began offering a master’s degree with workshops in writing poetry, fiction and plays.

The program supports several literary activities open to the public each year. They include the Castalia and Watermark Reading Series, the Roethke Memorial Reading, and the ongoing Reading and Lecture Series. Poetry Northwest has been published at the UW since 1960 and the Seattle Review since 1978.

When Johnson resumes full-time teaching in the fall, he will return as the first S. Wilson and Grace M. Pollock Professor of Creative Writing. The Pollock family has enthusiastically supported creative writing at the UW for many years. Loren Douglas Milliman, Grace Pollock’s father, taught in the department from 1904 until his death in 1937.

The Pollocks established the Milliman Award in Creative Writing in 1973, which has provided many students with scholarships. An additional gift in 1983 endowed the Milliman Writer in Residence, currently held by poet Heather McHugh. A 1987 gift created the Pollock Professorship and consolidated their previous donations into the Pollock Endowment for Excellence in English. This endowment was designed to attract and retain a distinguished writer and teacher in creative writing and generally support the writing program. To help the gift work even harder, the professorship received matching funds from the state’s Distinguished Professorship Trust Fund.

The professorship has already made its mark, since it was crucial in keeping Johnson at the UW. “Charles Johnson received a very generous offer this year from another institution,” notes English Chair Richard Dunn. “Without the Pollock Professorship, and the state match, he would be a distinguished faculty member at another university. Instead, we had the extra support we needed to keep him here.”