Lesley Everett, ’06, had no shortage of assigned reading as she worked toward her B.A. in biochemistry at the UW. Yet somehow, in the past two years, she managed to read the book Mountains Beyond Mountains three times. It’s the true story of Paul Farmer, a doctor who has devoted himself single-mindedly (and, in the beginning, single-handedly) to bringing modern medicine to the worst parts of the world -- something he decided to do when he was still an undergraduate.

Everett, who this month arrives in England to begin graduate work at Cambridge University, says the book is the perfect companion to a college education because it helps students “really think about how they want to use these four years.” She regrets only one thing: “I wish I’d read it when I first got here.”

The UW Class of 2010 will graduate with no such regrets. This fall, every new student will arrive at the UW owning a copy of Mountains Beyond Mountains, courtesy of the Office of Undergraduate Education. It’s the University’s first ever “Common Book” — assigned reading for all freshmen and transfer students, and recommended reading for the rest of the UW community.

“We’re trying to create a kind of a syllabus — a short syllabus — for the entire University,” says Christine Ingebritsen, professor of Scandinavian Studies, who came up with the common book idea while serving as acting dean of undergraduate education. She and her staff put together a yearlong program of activities around the book, including visits from Tracy Kidder, its Pulitzer Prize-winning author, and Paul Farmer himself (pictured above with Alcante Joseph, age 15, in Cange, Haiti). It’s an ambitious effort to give students the kind of shared experience they could easily miss at a huge, heterogeneous research university. It’s also — perhaps even more ambitiously — an attempt to get thousands of 18-year-olds thinking about the world beyond the Ave. and Facebook.com.

Author Tracy Kidder.

“I think that college kids, at least some subset of them, are just hungry for something that resembles meaning in this incredible age of consumerism,” Kidder says. “And honestly, I can’t think of anything more meaningful than people’s health, particularly the health of people who live in countries where the average life expectancy is now falling into the high twenties.”

There is no country in the Western Hemisphere poorer or sicker than Haiti, and no region of Haiti more miserable than its central plateau. Yet this is where Farmer — a Harvard-educated doctor and MacArthur “genius grant” winner — has chosen to spend much of his adult life. When Kidder first meets him, Farmer is living eight months of the year in a tiny house without hot water, working 18-hour days and making house calls that require 10-mile hikes through the mountains.

Kidder, like his subject, is a dispenser of strong medicine. Mountains Beyond Mountains moves briskly from the shocking to the grimly humorous to the heart-rending. In an early chapter, Kidder describes Farmer giving a spinal tap to a 13-year-old girl with meningitis: “The veins stand up on Farmer’s thin neck as he eases the needle in. Wild cries erupt from the child: “Li fe-m mal, mwen grangou!” Farmer looks up, and for a moment he’s narrating Haiti again. ‘She’s crying, “It hurts, I’m hungry.” Can you believe it? Only in Haiti would a child cry out that she’s hungry during a spinal tap.’ ”

Yet for all its bleak realism, Mountains Beyond Mountains is a profoundly hopeful book. Kidder chronicles the growth of the Zanmi Lasante clinic from a dream in Farmer’s 23-year-old head to a network of hospitals providing free medical care to millions of Haitians. It has become such a model of effective medicine, in fact, that treatments developed there and workers trained there are now being exported to other parts of the world. Partners in Health, the Boston-based medical charity founded by Farmer in 1987, has built facilities on four continents — in rural Rwanda, many of the doctors are Haitian. Kidder also follows Farmer to places like Peru and Russia, where he and his colleagues have helped get drug-resistant tuberculosis under control (proving a number of pessimists wrong in the process).

“I kind of reflexively thought, ‘Well, it’s not my place to proselytize for Partners in Health.’ And then I thought, ‘Well, why not?’”

Tracy Kidder

More than anything, the book demonstrates that what Kidder calls “effective idealism” is possible, and that it can be just as infectious as the diseases Farmer treats. Again and again in the book, people come around to Farmer’s way of thinking — even to his way of life. Ophelia Dahl, the daughter of movie star Patricia Neal and children’s book author Roald Dahl, meets Farmer when she’s 18 and almost immediately thinks, “Oh dear, oh good, my life has changed.” Twenty-three years later, she is executive director of Partners in Health.

Kidder doesn’t deny that he, too, fell under the good doctor’s spell. “The fact is that I came to this project with a certain amount of skepticism,” he says. “Over 30 years of doing this sort of thing, I’ve cultivated quite a lot of skepticism. But the thing about Farmer and company was that they weren’t just talking. They were showing me stuff. And what I really like is that I can’t see the ulterior motive. … The focus is on the patients and the potential patients.”

Following the book’s publication, Kidder began accepting invitations to speak at colleges and universities around the country. (The UW is not the first school to make Mountains Beyond Mountains its community reading assignment — more like the thirtienth, although it will be the first to bring both author and subject to campus.) “Once the book was published,” Kidder says, “I kind of reflexively thought, ‘Well, it’s not my place to proselytize for Partners in Health.’ And then I thought, ‘Well, why not?’ I went out into the world and I stumbled onto something that — in my experience, anyway — is extraordinary.”

Ingebritsen hopes the UW community will find Farmer’s story just as compelling. She wants to see students reading and talking about the book in coffee shops along the Ave., and has been planting copies around campus Johnny Appleseed-style. Every new faculty member has one, she says, as does every department chair in the College of Arts and Sciences. She has approved funding for several new courses that will use it as a text, and has established partnerships with First Year Programs, the UW Alumni Association and the University Book Store to help promote the common book cause. Mountains Beyond Mountains will be on the table in honors discussion groups and Freshman Interest Groups, where students will develop questions to ask Farmer during his Nov. 13 appearance on campus.

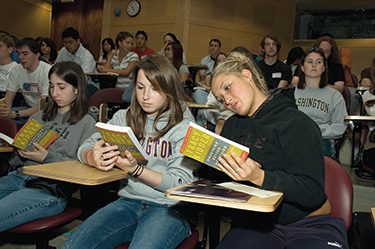

Incoming freshmen inspect their copies of the common book at a June 15 orientation. Photo by Kathy Sauber.

The selection of Mountains Beyond Mountains, Ingebritsen points out, is especially timely because it coincides with the founding of the UW’s undergraduate program in global health. Yet the book is about so much more than medicine, she says. It’s about the marriage of morality, intelligence and passion. Of all its qualities, the one she admires most is its versatility as a teaching tool — between Farmer’s mix of anthropology, epidemiology and ethics, and Kidder’s matchless skills as a reporter and prose stylist, Mountains Beyond Mountains is a one-volume liberal arts education.

“I’m always asked to go out and talk to potential students and their parents,” Ingebritsen says, “and what I tell them is, ‘Find your passion, and a major and then a career will follow.’ And to me, what Paul Farmer’s life represents is that discovery of a passion. That is what I would hope for any student here. And it’s not that I want every student to be Paul Farmer. But I’d like every student to be inspired by him.”

That may be a bit optimistic. When several hundred freshmen received the book at a June 15 orientation event in Kane Hall, they studied its cover suspiciously. The only one who raised her hand during a question-and-answer period seemed to want to know exactly how required this “required reading” was. “If you haven’t read the book, you will feel like you’re not on the train,” Ingebritsen told her.

“What Dr. Farmer did was bring concepts of suffering and structural violence into polite conversation. He also went down there and did something about it, as opposed to just lamenting it.”

Sunil Aggarwal, M.D./Ph.D. student

On the other hand, Mountains Beyond Mountains already has a history of speaking to students at the UW. Jonathan Mayer, a professor of medicine and geography, has been teaching the book since it was first published, and has seen it change lives. His former student Daphne Blake, a 35-year-old senior, says she admires Farmer for his refusal to look at problems in isolation — to see epidemics, for example, as unrelated to poverty. She wants to apply the lessons of Mountains Beyond Mountains to the work she was doing before she returned to school — educating child prostitutes in Thailand. “My plan is to develop programs that do more than just give them condoms,” she says.

Sunil Aggarwal, an M.D./Ph.D. student focusing on medical geography, hopes to be an advocate for the reform of drug laws and the humane treatment of prisoners. “I just try to keep a focus on who are the most silenced voices in our society,” he says. “What Dr. Farmer did was bring concepts of suffering and structural violence into polite conversation. He also went down there and did something about it, as opposed to just lamenting it. He’s a hero, for sure.”

Then there’s Everett, the aspiring epidemiologist, whose graduate education will be financed by an ultra-prestigious Gates Cambridge Scholarship. She idolizes Farmer, but can also relate to him.

“I’m 21,” she says, “and he was about the same age when he first started going to Haiti. And it was at that point that he realized, ‘I can do this here.’ To think that he was able to build those hospitals and lead that huge public health intervention down there, all starting so young — starting with, really, not much more of an education or a background or resources than I have right now — it’s so inspiring.”

Q&A with Paul Farmer, a doctor without borders

Photo courtesy of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Paul Farmer has trouble sitting still. By his second year of medical school, he was already taking such frequent trips to Haiti that his classmates were calling him “Paul Foreigner.” And he still keeps what literary journalist Tracy Kidder describes as “a lunatic schedule.” The easiest way to talk to him on the phone is to catch him in a car, which is what I did on June 15. He’d returned to Boston that morning on a red-eye flight from Seattle. The next morning he’d be flying—to Russia for a week, then on to Rwanda for the rest of the summer. —Eric McHenry

Tell me about the expansion of Partners in Health since the publication of “Mountains Beyond Mountains.”

I’ve got one word for you: Africa. That’s where we belong. That’s where the need is greatest, and I think that’s where we can make our greatest contribution.

What are your projects in Africa? AIDS and tuberculosis?

An even higher priority than that is working with the publichealth sector to strengthen basic, primary health care. Now to Partners in Health that includes AIDS and tuberculosis and women’s health and a whole passel of things. Sometimes we use the cover of one or two diseases to strengthen our work promoting basic rights, because that’s what we’re really about. We don’t always talk that way, but we’re about basic human rights: the right to health care, the right to clean water, the right to primary education. We’re doing all those things in Rwanda.

If you talked about it more explicitly in those terms, would you risk politicizing it in a way that might affect your funding? So you focus on the diseases because it’s more practical?

Yeah. Sometimes I do that. Although I always write about this explicitly in rights terms. But then again, no one but my mother reads my books.

Speaking of books, can you confidently say at this point that the publication of Mountains Beyond Mountains has helped Partners in Health?

Oh yeah, that’s for sure.

Tracy Kidder told me you were somewhat ambivalent about the book. And I’m sure that that kind of publicity is a double-edged sword. In retrospect, does it seem like a project that has dovetailed well with the goals of Partners in Health?

It’s dovetailed well with Partners in Health and its goals, yes. In terms of dovetailing with one’s personal ambitions, I’m glad Tracy told you and not me. I was uncomfortable with it. I took one for the team. But you know, he’s great company, and he certainly introduced the drama of what’s going on with the destitute sick in a way that I could not have done, and, evidently, very few other people could have done.

When you say you took one for the team … ?

I’m sort of joking. Let me put it this way: A narrative journalist has to tell a story that involves a small number of characters, otherwise he or she loses the reader, right? But we are hundreds of us working together. In fact, there are 4,000 people working for Partners in Health now. Most of them are community health workers. Most of them are Haitian. I know what it feels like to work as part of a big team. And some people will read Kidder’s book and say—you know, I think it’s even on the jacket somewhere—“one person can have extraordinary force in the world.” And I say, “No, no, that’s not at all the case. You have to work with lots of people to have impact in the world.” You’ve just returned from a meeting with the Gates Foundation, which has been a big source of support for Partners in Health.

They performed CPR on international health, let me tell you. They really did. They brought it back from the dead. It’s so much better now than even five or six years ago. One of the big problems in international health was that there were so few resources available that people had begun setting their sights lower and lower—people in my field. “We can’t do this. We can’t do that. We can only do this.” Sorry, but you can’t walk into an impoverished village in the middle of Rwanda and say, “OK, what are the cost-effective ways to intervene here?” Sometimes you have to invest very heavily in rebuilding infrastructure and making sure that whatever ails people is what you address. And that’s what we’ve done in Rwanda.

How do you feel about the book being chosen as a “common book”—not just by the University of Washington, but by all these secondary schools and colleges and universities and communities?

I’m very honored, because one, I’m a teacher, and two, I was a student activist. What we want to see is students—high school students, college students—getting involved in these issues. I’m thrilled about that. I decided I would go to Haiti as an undergraduate. And that’s something I really enjoy saying to students: “Hey, you can do stuff in college that can become a whole lifetime’s work for you, if you’re lucky.”