Kilroy was here ... and there ... and everywhere. Anyone old enough to have experienced the American landscape between 1942 and 1956 remembers that Kilroy left his name on rocks, bridges, buildings and—during World War II and the Korean War—even on walls behind enemy lines.

Kilroy may be history but today, in America’s inner cities, there are still graffiti scrawls “behind enemy lines.” Some gang graffiti serves as a billboard announcing to streetwise cognoscenti that “I sell drugs here” or “I shoot people who don’t belong here” or a warning that “You are passing into enemy territory.”

Other gang-related scrawls are simply expressions of a basic adolescent urge to establish groups and set goals. A list of names or nicknames (called “tags” in graffiti culture), for example, may simply mean “We hang out together,” says a UW expert in graffiti.

Whether it’s Kilroy’s name or a gang member’s “tag,” the writers are exercising one of graffiti’s most important functions: providing people with little access to other means of public expression the opportunity to be heard, explains Rick Olguin. An American ethnic studies professor, Olguin became interested in the subject as a graduate student at Stanford University and is now writing a book about graffiti.

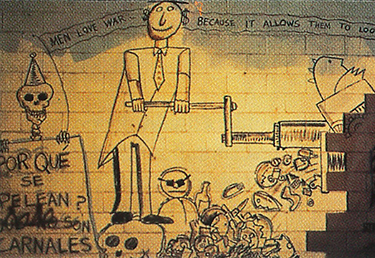

A 1976 photo shows both Anglo and Hispanic anti-war graffiti.

Actually, G.I.s and gang members are relative latecomers to this ancient medium of communication, protest and occasionally genuine art. The catacombs under the city of Rome, for example, bear names and symbols left by persecuted first century Christians.

Olguin describes visiting a ruin in Greece where one of the now-scattered building blocks bears a mark scratched into it by a stonemason 3,000 years ago. “At that moment something really clicked about this universal urge to write graffiti, or for people to write their initials in fresh cement or carve their name in a tree or a desk,” he recalls. “Fundamentally, graffiti is almost the universal way in which people express a fairly universal drive to be remembered.” And because it represents a universal human desire, Olguin deplores society’s tendency to “trivialize ” modern graffiti by “collapsing all of it into gang behavior.”

Olguin’s views notwithstanding, Sue Honaker, Seattle’s anti-graffiti coordinator, doesn’t hesitate to label as “graffiti vandals” the people who decorate walls that don’t belong to them.

Honaker can’t estimate how much graffiti removal costs the city of Seattle each year. But, she points out, the Seattle Public Library one year spent half its annual maintenance staff hours removing graffiti and Metro spent “well over $500,000” in one year cleaning graffiti from buses.

New York City spends $52 million annually in the battle against graffiti on its more than 6,000 subway cars, according to U.S. News and World Report. Last year, Time reported that annual U.S. costs run “into the billions.” Jay Beswick, founder of the National Graffiti Information Network, said in the same report that Los Angeles spends $28 million annually dealing with graffiti and Southern California cities together incur costs of $100 million.

“It's not a question of art. It could be the Mona Lisa, but if it's on the side of your house, your rights are violated.”

Sue Honaker, Seattle's anti-graffiti coordinator

“Basically, graffiti is any scrawl, writing, picture or marking on someone else’s property without their consent,” says Honaker, a 1984 UW alumna. “I don’t think there’s a person alive who has a problem with art,” she adds. “It’s not a question of art. It could be the Mona Lisa, but if it’s on the side of your house, your rights are violated.”

Olguin agrees that graffiti that encourages criminal behavior should be obliterated. But, he adds, society often fails to recognize that graffiti can also be art and a serious expression of cultural roots. “Not quite as complex as Navajo blanket weaving, but it has that kind of characteristic.”

Among Puerto Rican youth in New York City, for example, a master graffiti painter will draw out the mural and a group of apprentices, many of whom aspire to master status themselves, complete the project under his direction, says Olguin. “They’re seriously involved in learning a cultural aesthetic form of representation. It’s not just pure vandalism. … It’s art school just like Rubens.”

Olguin also ties graffiti to what he calls the “aesthetic of no empty space ” found in many cultures around the world. The walls of whole villages in remote parts of West Africa are painted in mural fashion, he says, and traces of these traditional motifs can be identified in African-American graffiti. “If these (African village) people occupied these offices,” he notes with a gesture toward the pristine perimeter of his Padelford office, “none of these walls would be white.”

Graffiti style makes its way into the mainstream in the lettering of this Chicano preschool sign.

The same aesthetic of filling empty space is also characteristic of pre-Columbian cultures. Walls in the ancient city of Teotehuacan, which 1,200 years ago had a population of 100,000, were entirely covered in floral murals, Olguin observes. Pre-Columbian designs, such as the feathered serpent or the step-pyramid shape, can be found today in graffiti in Mexican-American sections of cities such as Los Angeles and Albuquerque.

Olguin also ties the psychological mechanisms behind graffiti to the practice of ritual scarification (including the up-to-date “ritual scar” of pierced earlobes). He also likens it to tattoos (which he calls “personal permanent graffiti”), and even the current craze for message-bearing T-shirts, which are “thoroughly painless and another place you see all kinds of graffiti.” All of those practices, he says, reflect a deep human need to control our surrounding space.

Honaker, whose view is less academic, divides the graffiti she sees into several categories, including bubble gum (“John Loves Mary”), religious (“Jesus Saves” or “Allah Saves”), political, cartoon, gang and satanic which, she adds, is sometimes accompanied by evidence of animal mutilations such as a beheaded cat.

Each type of graffiti tends to have its own symbols. Satanist and white supremacist graffiti may be accompanied by the names of heavy metal rock ·bands such as Black Sabbath, Guns and Roses, Metallica and URU, Olguin notes. The pentagram, a five pointed star within a circle, is also a satanist symbol.

Disembodied heads are another common graffiti motif, Olguin notes, of which Kilroy, with his head and hands showing above a horizontal line, is a prime example. Chicano youth currently favor a front-view face with a goatee and perhaps a mustache, sunglasses and a fedora. Sculptors have been making disembodied heads for centuries whenever they create busts, Olguin points out. “It’s sort of canonical.”

One mysterious symbol that has cropped up in Seattle recently is a “weird squiggle,” in Olguin’s words, that at first glance suggests an Asian language. But experts at the Jackson School of International Studies have not been able to identify it. Sometimes, upon close inspection, the images resemble Roman letters elaborated almost to the point of being illegible, much like some of the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages, notes Olguin, who remains mystified about what the messages signify or who is writing them.

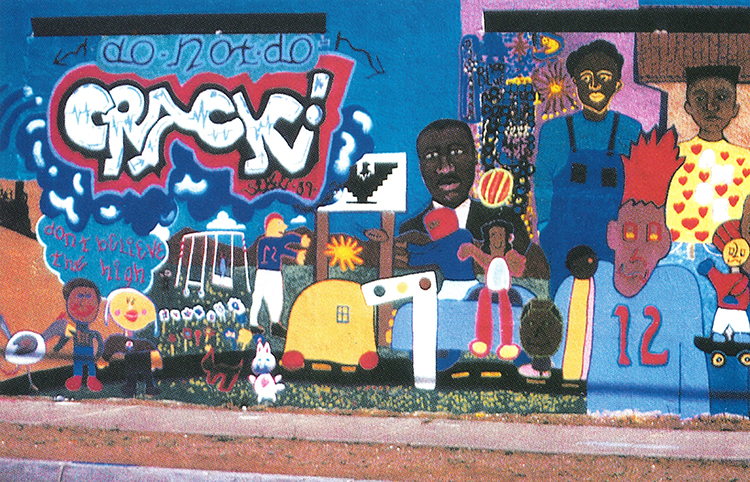

A 1990 mural in Albuquerque, New Mexico, painted to discourage drug use, employs street graffiti styles.

Contemporary writers of political graffiti have adopted 19th century anarchist symbols such as a black flag or the letter A inside of a circle, Olguin notes, although he doubts they understand classic anarchist philosophy. “To them, anarchy means ‘There are no rules,’ which is different from ‘There is no government,’ which is what anarchy is about.”

As is often the case in popular culture, California can be a trendsetter in graffiti. Corporate symbols, such as the familiar bell of the telephone company, the logo of the Los Angeles Raiders, or oil company logos are popular territorial markers for Los Angeles gangs, says Honaker. “El Norte” and “El Sur” are gang designations seen throughout Northern and Southern California respectively. Such designations, including the gang names Bloods and Crips, tend to make their way north. One of Olguin’s friends has seen the word “Surrenos” in a neighborhood in West Seattle, the mark of a group of kids from a neighborhood in southern Orange County.

In contrast to some cities, Honaker notes, only about two percent of Seattle’s graffiti is the work of true gang members. Olguin agrees that the percentage is small. Most gang-type work is “copy cat,” in Honaker’s words, but she declines to make public the clues that allow her to tell the difference.

If gang graffiti is an expression of “I belong,” hate graffiti is a statement of separation, Olguin says. “You get a real statement of identity, not through connection to a space but through definition of an outgroup: ‘I am not gay’ … ‘I am not black’ … ‘I am not woman.”‘

The campus has seen a recent “flurry of really ugly racist stuff,” says Anne Guthrie, administrative manager in the UW’s facility management office. Guthrie ties the wave to a resurgence of racism both here and on American campuses in general. Official policy calls for the prompt removal of all graffiti, says Guthrie, but special efforts are made to remove racist and sexist scrawls within 24 hours.

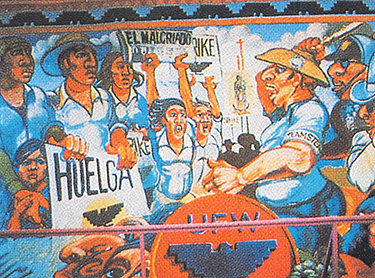

A mid-1970s mural in San Diego that promotes the United Farmworkers has not been defaced by graffiti in more than 10 years.

Political graffiti is also popular on campus, and is usually aimed at political and military hot spots from El Salvador to the Middle East. Favorite locations seem to be the west wall of campus facing 15th Avenue N.E., the back wall of Kincaid Hall near the Burke Gillman Trail and “Red Square” near the Odegaard Undergraduate Library, Guthrie says. The stairwells from the Central Plaza Garage are another popular target.

To Guthrie’s knowledge, no tally is kept of how much money and staff time is spent removing campus graffiti. But, she points out, in an era of limited budgets, every dollar or hour devoted to graffiti removal is that much less available for other, badly needed, purposes.

Removal techniques and costs vary according to the surface and the kind of paint used. Concrete can be painted over, cleaned with high pressure water hoses or sprayed over with what Honaker calls a “slurry” that, in effect, applies a thin layer of new concrete.

Brick and marble surfaces are especially expensive to clean, Honaker notes, and often require the use of chemicals which pose an environmental threat when they make their way through storm drains into rivers or other bodies of water.

Like Olguin, Honaker spends considerable time on the street getting to know the youth who engage in the graffiti. She tries to “stay away from the punitive” and works hard to maintain good relationships with known graffiti vandals who keep her up to date on “what’s new on the street,” she says.

Her experience leads her to believe that graffiti vandalism is an essentially anonymous behavior which permits individuals to, in her words, “rile without risk.” Youngsters who have failed to attract approval through academic, social or athletic achievement can, through graffiti, command a moment in the sun, she notes. Take, for example, the New York City youth who slipped into a zoo at night and spray-painted graffiti on the back side of an elephant. “He had a good story to tell at school the next day,” Honaker notes.

Most youthful vandals are from the lower economic levels, Honaker says, but the activity also attracts affluent children who “put up graffiti or run with a tag team” as a way to add a sense of risk to otherwise orderly, safe lives. A “tag team,” she explains, often consists of an artist, a lookout, and someone adept at stealing paint—which can be a major undertaking and is often a point of honor in itself. “A good piece can take as many as 500 spray cans,” she adds.

Whenever possible Honaker tries to persuade the best of the painters to design and paint murals on walls offered for that purpose by Seattle business people. The city already boasts dozens of such productions.

“There’s a lot of really good talent out there,” she notes. “Good people who are misdirected.”

Olguin urges that we work harder to re-channel not just the art but also the energy of the youths who participate in it. These youngsters, with their graffiti and gang behavior, are exploring the limits of society’s rules, he notes. “It seems to me that (exploring these limits) is what entrepreneurial societies are all about, what aesthetically creative and dynamic societies are all about.”

At top: A 1990 photo of a retaining wall on Rainier Avenue South in Seattle that is covered with hundreds of “tags.”