At peace with the past At peace with the past At peace with the past

Decades after serving in the Vietnam War, Dr. Mike Fey returned and developed a dental curriculum in Hanoi.

By Rachel Gallaher | Photos by Mike Fey | December 2023

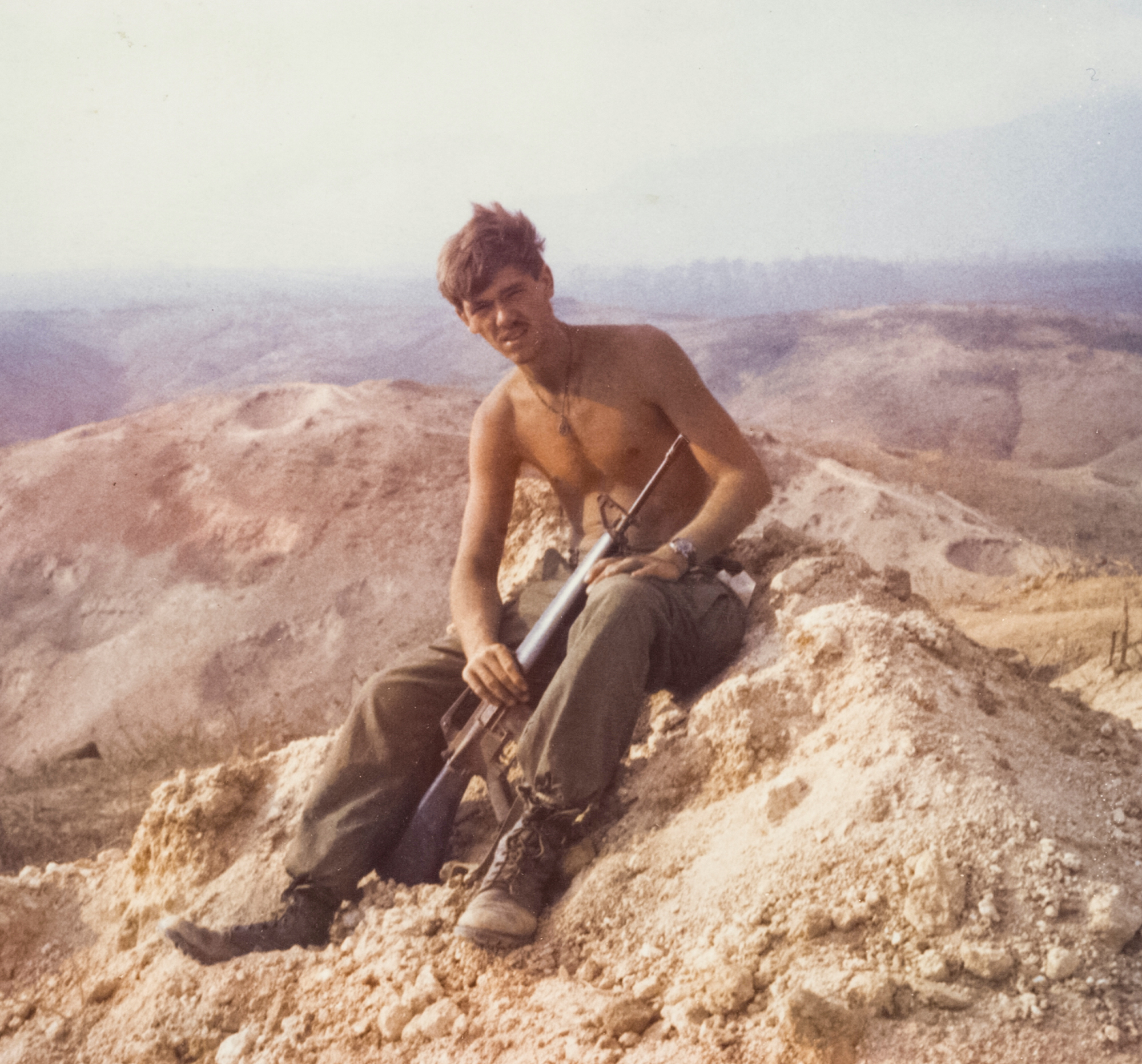

On a dark December night in 1967, four young men stood together in the barracks at Fort Polk, Louisiana, a one-dollar bill held between them. The quartet had spent the previous six months together, starting with three months of basic training at Fort Lewis, Washington, followed by another three at Fort Polk, where they completed advanced infantry training. Now, the men, in their early 20s, were on the precipice of a life-altering assignment: they would be heading to Vietnam the next day. In an act of solidarity—with a dash of youthful hopefulness—they tore the dollar bill into four sections, each tucking their quadrant into a pocket or wallet for safekeeping. The plan was that each would take their piece with them, and they would eventually reunite after the war.

“As far as I know, only three of us made it back,” says Dr. Michael Fey, who was a 21-year-old private at the time. “During the war, I always had three things with me: my camera, three photo albums with pictures of my family and my fiancé Donna, and that piece of the one-dollar bill.”

Fey was lucky to make it back—he spent a year in Vietnam and received two Purple Hearts after being wounded in action—and as soon as he arrived home to Seattle, he buckled down and forged a solid path forward. “I spent two months in the hospital in Japan,” he says, “and it gave me perspective. I told myself that if I came home, which was not guaranteed, I was going to push myself to the limit and do the best that I could in life.”

It wasn’t that Fey was a slacker or a poor student—he had adequate grades and had spent the last two years of high school playing on the tennis team at Highline High School. What he lacked was focus. A sense of direction. “I spent a lot of time hanging with my friends, goofing off, playing tennis,” he admits. “My parents told me, ‘We aren’t going to send you to a four-year college until you have a vision.’”

Vietnam’s countryside has been an eye-opening study in contrasts over the past 60 years, from the war-ravaged, bombed fields and hills in the 1960s to the spectacular rice fields that can be seen today. (Photos from Mike Fey’s book, “A Faraway Place.”)

After graduating in 1964, Fey enrolled at Highline College, the first community college in King County. He spent a year and a half there before transferring to the University of Washington in 1966 to study pharmacy. By then, the United States had entered the Vietnam War, and the government required all men ages 18 to 35 to sign up for the draft. “A deferment was granted to those who were enrolled in college and continued normal progress towards graduation,” Fey writes in a self-published personal memoir and photo collection titled “A Faraway Place: Revisiting Vietnam.” “So, by being in college, I thought I was safe from the war.”

Fey adapted quickly to life at the UW. He attended classes, worked at a local menswear store and caught the attention of Donna—an attractive student in several of his chemistry classes. Soon, they were dating.

According to Fey, within a month or so of his and Donna’s first date, “the draft caught up with me.” Some of his credits from community college hadn’t been accepted by UW, thus flagging him as not having made “normal progress” toward a college degree. Fey appealed to the draft board, but “it was the height of war,” he recalls. “I pleaded my case, and they just kind of laughed and said, ‘Well, son, they’ll probably just put you in pharmacy, and you’ll come out and have your GI benefits and can finish your education.’”

Mike Fey (right) and a group of Vietnamese children are all smiles. his photo was taken by Mr. Cu, owner of the Mandarin Cafe who was known for his banana pancakes. Mr. Cu was also a professional photographer and tour director who during the Vietnam War served as a fireman on an American military base. He stayed in Hue and he and Mike developed a friendship through their passion for photography.

After his unsuccessful appeal, Fey found himself in military training in the summer of 1967, and by that December, he was on the ground in Vietnam. Fey doesn’t go into much detail about the war—it’s an experience he attempted to put behind him upon returning to Seattle in 1968. “My kids didn’t know until they were in college that I fought in the war,” he says. “Like many soldiers, when I left, I vowed I would never go back.”

While serving, Fey took hundreds of photos that captured the experience better than words ever could. Flipping through “A Faraway Place,” one encounters dozens of young men thrown into unfathomable chaos thousands of miles from home. Smoke-filled fields, baby-faced boys with guns, and helicopters and tanks descending into territories unknown. There also are everyday tableau: two soldiers taking a field bath in a stream, someone getting a haircut and enlisted men interacting with local children.

After returning to Seattle, Fey re-enrolled at the UW and doubled down on academics, receiving his degree in pharmacy in 1971, a DDS in 1975 and a combined pediatric dentistry and orthodontics certificate in 1978. “One professor, Wendel Nelson, took me under his arm,” Fey says. “I conducted research [projects] for him, and the work motivated me. I realized I could do whatever I wanted if I really worked at it.” Fey went on to spend more than 40 years in dentistry as an educator at the UW and running an orthodontics practice. (His daughter, Dr. Kristina Grey, ’98, took over when Fey retired in 2016.)

In 2000, Fey returned to Vietnam. “I was drawn back primarily because of photography,” he says. He and Donna had become involved with a Bainbridge Island-based nonprofit called PeaceTrees Vietnam. Founded in 1995 by Danaan Parry and Jerilyn Brusseau (whose brother Daniel Cheney was killed in the war), PeaceTrees Vietnam was the first U.S. organization permitted to sponsor humanitarian demining efforts in Vietnam. Since its launch, the group has cleared 3,265 acres of land.

During a visit to Hanoi in 2010, Fey’s wife, Donna, joins a group of employees and students at a new orthodontic clinic within the dental institute in Hanoi.

Fey and his wife made their 2000 trip with PeaceTrees Vietnam. “Before we left, a friend and colleague reached out,” he recalls. “He had worked in a clinic and helped at the Hanoi School of Medicine. He said, ‘Would you be interested in coming by while you’re there?’” Fey and Donna were interested, and during their visit, they learned that the training techniques and requirements to become a dentist were very different from those in the United States. In Vietnam at the time, dentistry was under the umbrella of medicine—there were no independent dental schools.

During a second visit, in 2002, Fey listened to leaders at the institute as they talked about wanting to separate the two departments and establish an independent dental institute with a new curriculum. “With my background in dental education and curriculum, I was curious about the curriculum design for the new school,” Fey writes in his memoir. “The rector and vice-rector invited me to participate in the overall curriculum development, but more specifically, the orthodontic and pediatric sections. Thus began another journey that added to my personal richness with the next eight years.”

Fey and Donna threw themselves into helping the cause—guiding the curriculum development, helping establish a library and an orthodontics department, and teaching conversational English. Although the vision for establishing an independent dental institute has yet to be realized, Fey helped develop a distinct path for training dentists separately from medical doctors. He calls the year spent in Vietnam during the war “the lowest point in my life,” but his unexpected return brought about a new sense of purpose and a new passion for the country he once pledged never to step foot in again. “I’ve met a lot of interesting people and made a lot of good friends along the way,” Fey reflects. “I love teaching, and I’m glad I had the opportunity to share that.”