Master

of his fate

Master

of his fate

Master

of his fate

Wallace Loh’s journey to the deanship of the UW law school is a remarkable tale of lost riches, cruel humiliation and human triumph.

By Nancy Wick | Photos by Mary Levin | Dec. 1990 issue

If world events had played out differently, Wallace Loh might have become the Donald Trump of Shanghai. If Loh himself had been different, he might have become the proprietor of a mom-and-pop grocery store in Lima, Peru.

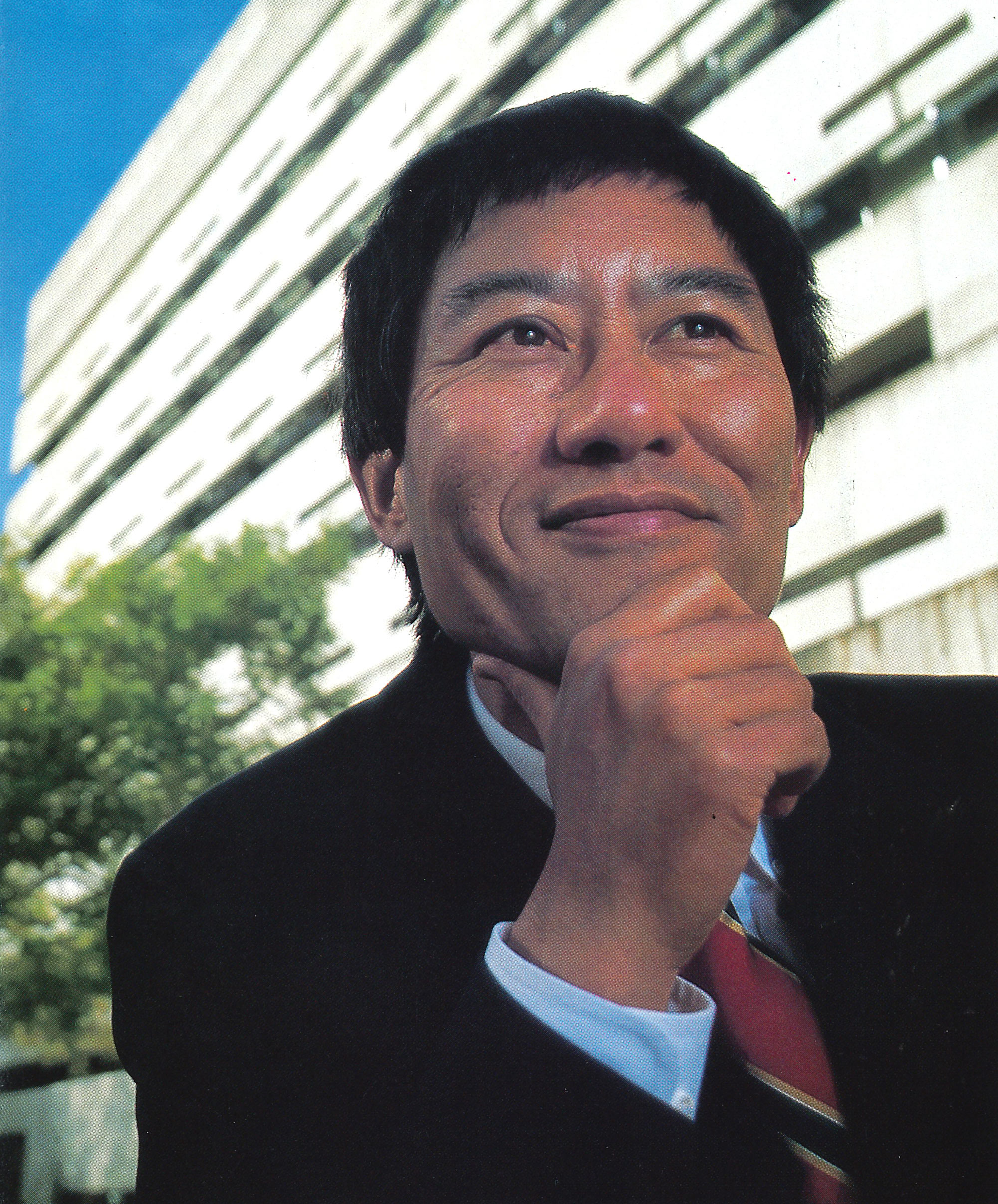

Instead, Loh found his way to the UW School of Law, where last May he became dean, the first Asian American to head a law school in the United States. This distinction came despite the fact that the first time he tried to become a lawyer, every law school he applied to turned him down.

Who is this remarkable man? Ask about him in Condon Hall and the first thing you’ll find out is how hard he works. Colleagues, staff and students alike are apt to talk about his dedication. Small wonder; Loh admits to putting in 60- to 70-hour weeks.

“I jump out of bed at 4 a.m.,” Loh says. “I can’t wait to get to work.”

But putting work first has not made Loh remote and unapproachable. Former student Barbara Selberg remembers him coming to class in running shoes. “He always wore a tie, but the first thing he’d do when he came in was to throw it over his shoulder,” Selberg recalls. “It was like, ‘Let’s get this thing out of the way and then we can get down to business.’”

“I use more of what Wallace taught me than anything else I learned in law school,” enthuses another former student, Jay Kornfeld. Kornfeld, who now specializes in bankruptcy law at a Seattle firm, took every course Loh offered, none of which had to do with creditor/debtor law.

Looking into Loh’s past, it’s not hard to find the roots of his present style. He was born in Chongqing, China to a wealthy family in 1945. His grandfather owned substantial property in downtown Shanghai, and as his mother’s only son, Loh’s name still is on the deeds to that property.

“I knew that if I stayed, I would end up running my father's store.”

Wallace Loh

But the Chinese revolution wiped out any chance he might have had to practice “the art of the deal,” Shanghai style. Loh’s father had been named ambassador to Peru in 1947, so the family was living in Lima when the 1949 revolution came. Suddenly without a position and branded a political criminal, the senior Loh decided to stay in Lima and open a grocery store.

The store was the center of Loh’s early years. “I had no childhood,” he says candidly. “That store was open from 7:30 in the morning until 10:30 at night, seven days a week. Every minute I wasn’t in school, I was working in that store.”

The Lohs were not alone in their business endeavor. Asians, Loh explains, emigrated to Peru in large numbers in the 1920s and ’30s. By the time his family arrived, most of the Chinese were running grocery stores. In fact, the Spanish phrase used in Peru for “going to the grocery store,” translates literally as “going to the Chinaman’s.”

Loh grew up with two first languages—Chinese and Spanish—but he was an outsider in the Peruvian society. Prejudice against Asians was pervasive. “The history books at school described the Asian emigration as ‘the yellow calamity.’ My teachers would sometimes address me as ‘Hey Chino (Chinaman),'” Loh says. For the most part, he let these insults roll off his back.

“It was matter-of-fact,” Loh explains. “It wasn’t done with animosity. These were the same teachers who treated me as teacher’s pet because I was doing well in school.”

But an incident while he was in high school was different. During an assembly, a visiting performer sang a song ridiculing the Chinese. Loh got up and left, finding the same abuse he accepted from his teachers to be intolerable coming from a stranger. He was rewarded with a week in detention.

At 15, Loh looked around and realized he had no future in Peru.

“There were no professional role models for me there,” he says. “I knew that if I stayed, I would end up running my father’s store.”

The family had little money, but Loh obtained some American college catalogs and turned to the financial aid sections. He went to Grinnell College in Iowa because it offered him a scholarship.

If being a Chinese kid in Peru was difficult, being a Chinese kid in Iowa in 1961 was hardly a piece of cake. A short time after his arrival, Loh asked his American roommate when the maid was coming to take their laundry. “Even lower middle class people in Peru had a maid,” Loh explains, “so I naturally expected the same thing here.”

The roommate told him he would have to make special arrangements with the “head maid,” who was called the Dean of Women. The naive Loh made an appointment and took his laundry to the dean’s office, where the roommate and several friends waited to witness his humiliation.

“To her credit, that woman never let on what was happening,” Loh says. “She took my laundry and returned it to me later, explaining to me privately the trick that had been played. I learned something from her that I haven’t forgotten: Never humiliate a student.”

Loh had arrived in Iowa alone, with his parents’ life savings of $200 and very rudimentary English skills. That he has succeeded—both professionally and financially—is a source of great pride to him.

But he hasn’t forgotten where he came from. Since his move to Seattle in 1974, Loh has volunteered his time to help immigrants make their way in the community. He has also been a source of special support to minority students in the law school. Selberg, who is black, says Loh has been a primary reference for her, instrumental in helping her find employment.

Giving back what he has received and helping others succeed are simply part of Loh’s philosophy. He describes himself as an “engaged scholar”—someone who communicates his study results for the purpose of promoting social change. While at Grinnell, he participated in civil rights activities, including a voter registration drive on Chicago’s South Side. After graduation, he applied to both law schools and graduate psychology programs. Every graduate program except one (Harvard) accepted him, but every law school turned him down.

Was discrimination the reason? Loh shrugs. “It’s hard to say. It’s true that my LSAT scores weren’t that good, but neither were my GREs. It’s also true that law schools tend to be more conservative than other university programs.”

Even if he had been given a choice, Loh says it would have been a “close call” between law school and graduate school. As it was, he went off to a Ph.D. program in social psychology at the University of Michigan, and afterwards, he accepted a Congressional fellowship to work on a U.S. senator’s staff.

“It only took me about two months to discover that almost everyone on Capitol Hill was a lawyer and that if I wanted to have an impact, I needed to know about law.”

It was about that time that the Russell Sage Foundation started a program to put Ph.D.s in the social sciences through law school. Loh took advantage of the program, thinking he would take only one year of law school, then return to Washington.

Instead, he earned his JD at Yale and has since specialized in the application of social science to the law, fulfilling his “engaged scholar” dream in a different way than he had envisioned.

“My interest is the law in action, as opposed to the law on the books,” Loh explains. “Book scholars might be interested in whether a law is logical and consistent with precedent; I’m interested in how it works in real life.”

Loh came to the UW as an assistant professor of law and adjunct in psychology. He was so focused on work that he spent the better part of his first year without a home. He slept in his office, took showers at the gym and ate in Terry-Lander residence hall. When the fire marshal found him one night and told him he’d have to sleep elsewhere, he rented a room.

* * *

Dean Loh chats with law school students in Condon Hall.

A single man not yet 30 at the time, it never occurred to Loh that he might have a personal life. He didn’t marry until age 40 and only became a father a year ago. He laughs when asked about it. “I’m a late bloomer,” he says. “I never even went out on a date until I’d finished my master’s degree.”

Loh’s dedication to work brought him a full professorship by 1980 and an associate deanship in 1989, the same year law students voted him Outstanding Teacher of the Year. Though beloved by students, Loh has no close ties among faculty. He describes himself as a “loner” who is not allied with any faction of his colleagues—a situation he thinks will help him be a good dean. Loh has said many times, in fact, that the theme of his administration will be “to unite and to build.”

His rise to the deanship came only after the prime candidate—a nationally prominent Asian law scholar—turned it down, citing inadequate financial support. A furor followed, including a student protest march through “Red Square.”

Because of all the commotion, he says, people have been very curious about the new dean, and that has given him many opportunities to “show the flag” of the law school in the community. “Besides,” he says, “I was pleased to have been considered for the deanship at all. Any of the finalists would have been great.”

Nevertheless, Loh has complete confidence in his own ability to do the job. When asked why he applied for the deanship, his answer is direct: “Because I wanted to build the law school and I knew I could do it.”

The positive statement is characteristic of Loh. Selberg recalls a time when she was taking contract law with him, and the confused class demanded to know if they would ever understand the subject.

“Wallace said ‘Yes,’ and we said ‘When?’ And he gave us a date, an actual date.” Selberg laughs, then adds, “And you know what? He was right.”

Being positive, however, does not mean Loh will be a dictatorial dean. “A dean provides an overall vision,” he says, “but not an agenda. The agenda emerges from the faculty.” He looks around, searching for words, then says finally, “This isn’t a job; it’s a cause.”

The fate of the Law School

Wallace Loh’s plans for the law school fall into two general categories: a commitment to diversity and to new initiatives that are of an interdisciplinary or public service nature.

“Out of 183 law schools in the nation, one-third have monochromatic faculty,” Loh points out. “And of 406 partners in major law firms in Seattle, only seven are minorities.”

Loh wants to see a joint effort by the law school and the area’s legal community to help break the “glass ceiling” in the profession.

Concerning new programs, Loh has several ideas in the works. The proposed Center for Law, Science and Technology would expose law, engineering and international studies students to the growing interrelationships between their fields, with a focus on technology transfer to the Pacific Rim. A similar purpose would be served by a proposed program in health care law, led by a faculty member with a dual appointment.

Loh also envisions a Center for Legislative Research, which would work with the state legislature on drafting and evaluating the impact of legislation, and a Center for Cooperative Law, which would undertake teaching and research in the gentler arts of mediation and reconciliation, rather than confrontation and litigation.

All of these ideas are in their infancy, and require the backing of the faculty and the legal community. But Loh is optimistic. “Provost (Laurel) Wilkening has announced that recruitment of minorities and women and interdisciplinary initiatives are priorities for her, so there’s a good fit between where the University is going and where I would like the law school to go.”