Fifty years ago, Lois North and Peggy Joan Maxie, ’72, two of just eight women in the Washington state Legislature, worked on an equal rights amendment to the state constitution. North, a Republican, and Maxie, a Democrat and the first African American woman elected to the Legislature, found bipartisan support for the effort. This included Gov. Dan Evans, ’48, ’49, a Republican, the Seattle League of Women, the ACLU, NAACP, the Washington Federation of Republican Women and the Young Republicans of King County.

With voter approval, Washington became one of the earlier states to ratify a gender equity amendment (though in 1890, Wyoming passed a broad amendment that included sex and race), but it was a long time coming. The first efforts, nationally, started 50 years earlier, says Kim England, director of the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies at the UW. It was in the wake of the success of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing women the right to vote. “There was a lot of vitality and excitement about what else could we pass,” she says. A first effort to secure full equity for women went to Congress in 1923. But it was buried in committee.

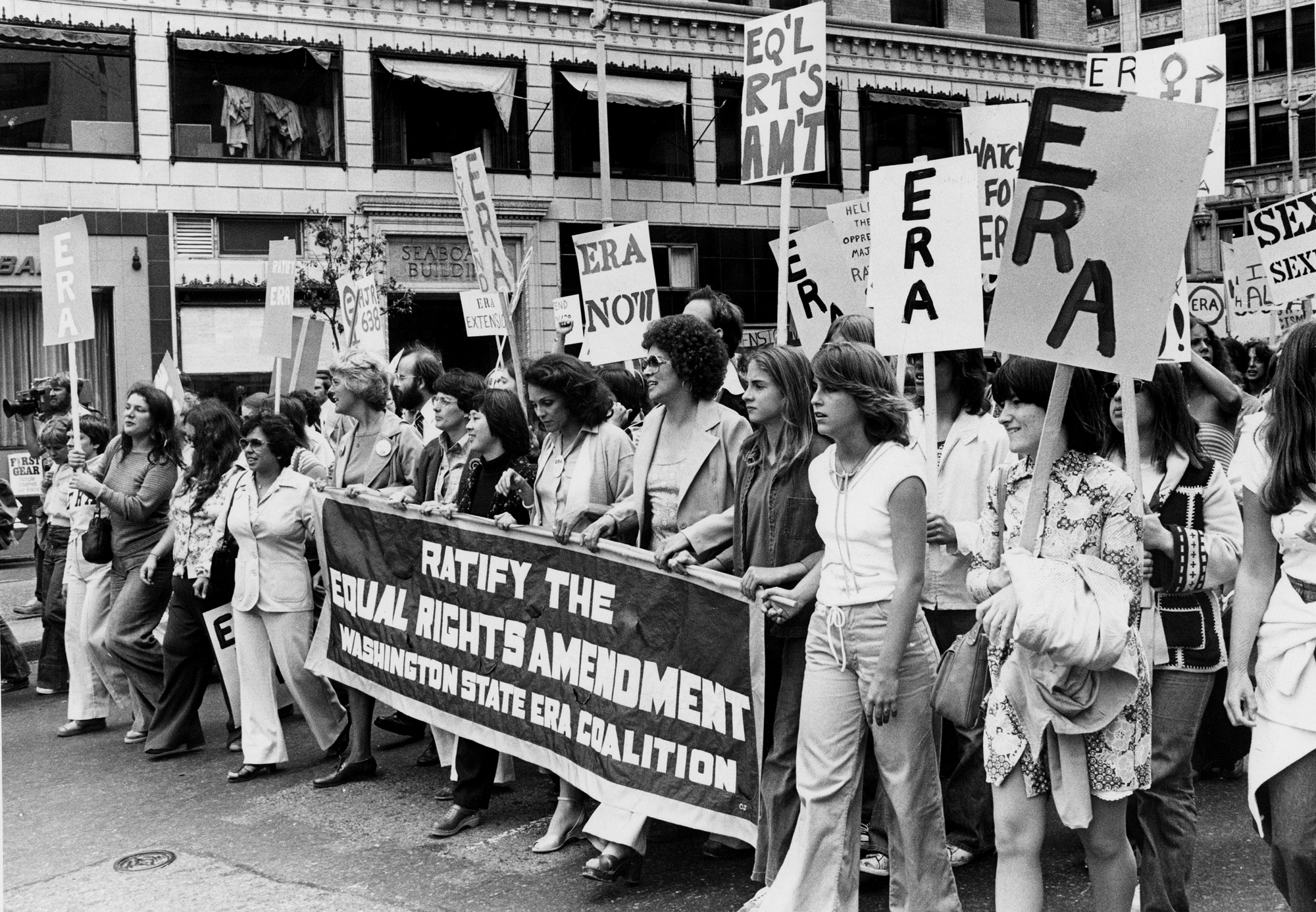

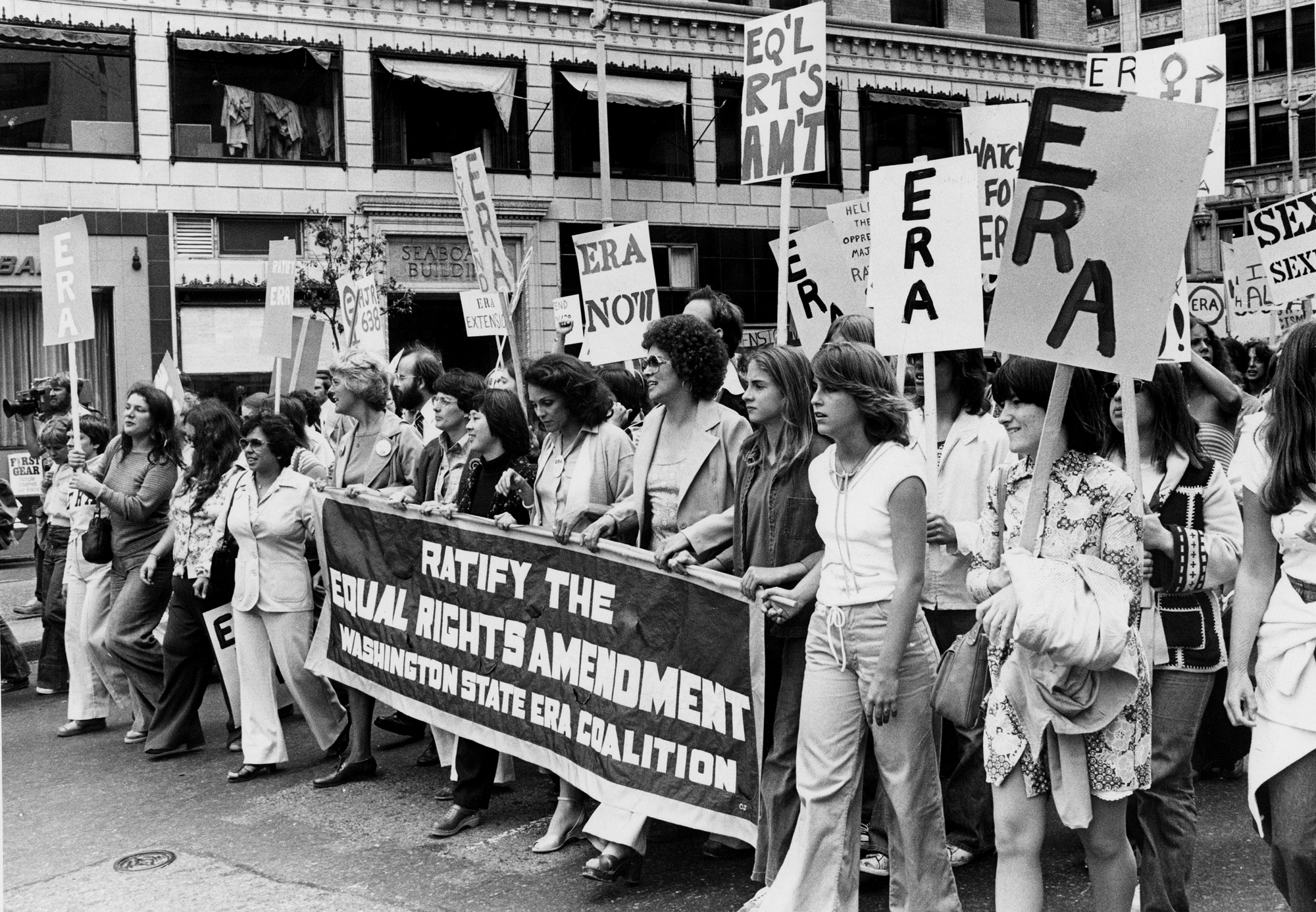

In the late 1960s, a new women’s movement arose. The National Organization for Women led the effort to revive the amendment and by 1972, it had the approval of both houses. From there it was up to the states to ratify. The ERA needed the ratification of 38 states. That’s when the opposition came out strong, England says.

Both nationally and locally, those opposed to the ERA focused on similar concerns. “Really it was a struggle around where is women’s place,” she says. It was a time when women couldn’t apply for credit without the co-signature of a man. Some of the arguments against it claimed that it would lead to same-sex bathrooms and same-sex marriages. “It is fascinating that those things have come to pass regardless,” says England.

By amending the constitution instead of creating a law, the legislators and voters did something more powerful and unalterable.

In Washington state, according to a 1972 voters guide, opponents argued that women would lose “certain preferential treatments” such as special rates for auto insurance, that girls would have to compete with boys in sports like “high school wrestling,” and divorce settlements would be less advantageous to women.

That November, voters approved the amendment. “It wasn’t just an easy pass,” England says. “The opposition took people by surprise.” There were 645,115 votes for and 631,746 votes against. Absentee ballots in King County put it over the top.

As a student, Maria Hodgins, ’20, wrote about the state ERA for the Washington Law Review. Though rarely used, it is still a powerful legal tool, she says. By amending the constitution instead of creating a law, the legislators and voters did something more powerful and unalterable.

It has appeared in just a few court cases over the past five decades. Nonetheless, simply having a state ERA increases the prospect of judges applying a higher standard of law in sex discrimination cases, Hodgins says.

Maybe someday there will finally be a federal equal rights amendment, something powerful and permanent, she adds. “I hope it happens in my lifetime.”