“They’re stuck with each other and they’ve got to ride all the way to the end of the line and it’s a one-way trip and the last stop is the cemetery.”

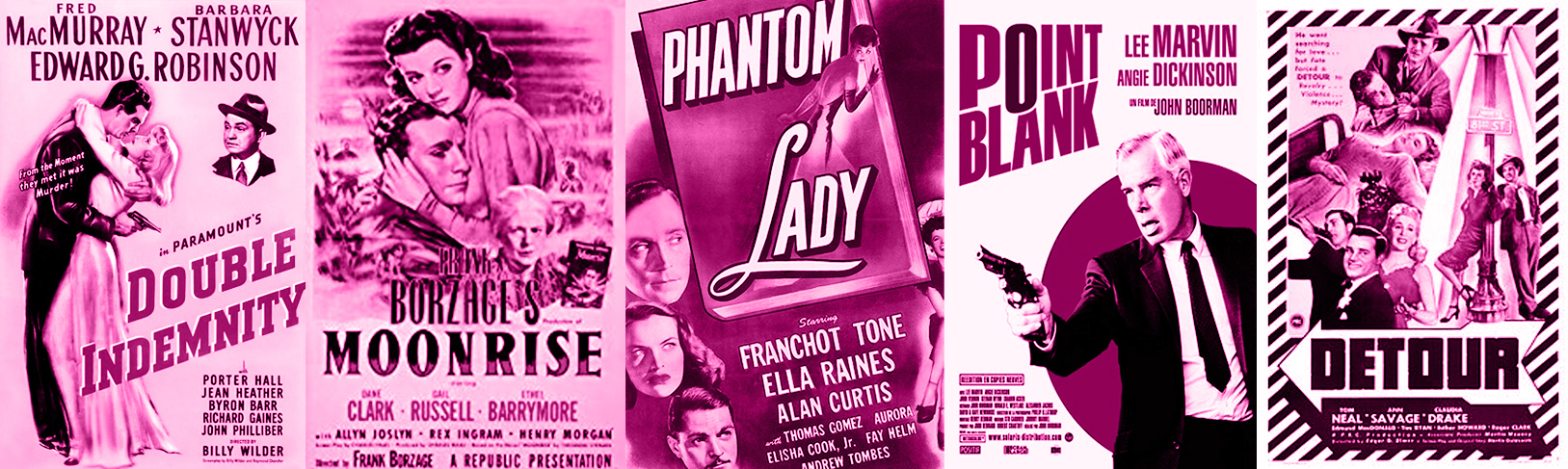

Double Indemnity (1944)

In 1969, Greg Olson was a man without a job. With a degree in English and newly married, he had few prospects on the horizon. His work experience to date included: writing film reviews for the UW Daily, temping for the post office, operating a movie projector for home screenings in the Highlands and handling miscellaneous duties for the Henry Art Gallery and a local film crew. Still, when he was hired as a shipping assistant at Seattle Art Museum, Olson saw it not as another fill-the-gap job, but an opportunity to create the future of his dreams.

A half century later, Olson, ’67, is celebrating his 50th anniversary at SAM, where he founded the institution’s acclaimed film program and initiated the world’s longest-running film noir series, begun in 1977. As a pillar of the Emerald City’s vibrant movie culture, Olson champions local filmmakers, searches out rare prints of classic and little-known movies, and dazzles film buffs with in-depth looks at great directors and actors from around the globe. He partners with other institutions and participates in annual programming around the cult-worshiped TV series “Twin Peaks” that draws David Lynch devotees from far-flung places.

Olson is a leading authority on Lynch. He researched and wrote the legendary director’s comprehensive biography, “David Lynch: Beautiful Dark” and is completing a new book on the series, “Twin Peaks: The Return.” Olson’s low-key manner cloaks the steely tenacity and self-confidence it took to build a successful career as a film programmer and writer. He credits growing up in a book-filled household with parents who appreciated culture and encouraged his interests.

Movies were always part of the mix. As a kid, Olson thrilled to the smart, stylish British horror and sci-fi movies of Hammer Film Productions, like “Horror of Dracula” and “The Creeping Unknown.” He even imagined going to work for the studio one day. Hollywood classics also helped shape his view of life: “I grew up on John Wayne movies, where the masculine hero guy saves the woman—those archetypes.”

Olson’s dad, Carl, was his original hero, a lumberjack off the boat from Sweden, a man with little education who went on to found a successful grocery business, Olson Brokerage Co. His mother Nona, of Russian heritage, and his aunt Pat, who lived with the family, were strong women who ignited Olson’s admiration for accomplished, assertive females. “The women in my life were outspoken, a force to be reckoned with,” he recalls. “Truffaut made a movie called “The Man Who Loved Women.” My inner voice said, ‘Right.’”

Growing up as an only child in the 1950s, Olson gravitated to adults. It was the dawn of the “Mad Men” era and his parents had built a house on the shore of Lake Sammamish. He remembers his dad’s business associates and their wives coming over from Seattle for parties, the men in shirts and ties, smoking, drinking highballs. “I loved those guys and they loved me. I wanted to be grown-up really fast, making moves, really cool … part of the grown-up world of the movies.”

In high school, he subscribed to the Village Voice, smitten with the abundant cultural life of New York City, and kept up with the latest developments in pop art, rock ’n’ roll, the political upheavals of the 1960s and the movies of Andy Warhol. He learned that films could be considered works of art and that the Museum of Modern Art had been showing film as early as the 1930s.

When he enrolled at UW, Olson followed his love of literature and writing into the English Department, with no clear idea where it would take him. But in his senior year, Olson signed up for the one film class available: The History and Aesthetics of the Motion Picture, taught by drama professor Vanick Galstaun.

What a vortex of pent-up movie passion that class turned out to be! Olson and his coterie of fellow students were an extraordinary group who would go on to become leading forces in the film and cultural life of Seattle and beyond: John Hartl, ’67, film critic for The Seattle Times for 50 years; Bill Arnold, ’69, author and film critic for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer for 30 years; Richard T. Jameson, critic and editor of Film Comment, New York; Roger Downey, ’65, longtime writer and critic for Seattle Weekly and other publications; Kathleen Murphy (who married Jameson) and Peter Hogue, both film critics and teachers; and Don Bartholomew, who ran audiovisual services at UW. Arnold recalls Jameson later facetiously dubbing it, “The class the stars fell out of.”

Like others in the class, Olson would try his hand at writing movie reviews—in his case, for the UW Daily—but quickly realized that was not the path for him. Reviewing was fun, he says, but “I wanted to preserve the childlike joy of being in a theater—not having to take notes and scramble to meet a deadline.”

The year after graduating, with few job prospects, Olson took a filmmaking course at Cornish College of the Arts. When that was over, he worked with his instructor on films for the Department of Motor Vehicles about the effects of alcohol and marijuana on driving. The project lasted eight months; then Olson was back to looking for work. One day his wife, Pamela, an artist, told him that Seattle Art Museum had an opening for a shipping assistant. Their marriage ended soon after, but the job turned out to be good fit.

“Sometimes, murder is like love. It takes two to commit it.”

Moonrise (1948)

Those were “the glory days” of SAM, Olson recalls, when the museum was housed in its original jewel box Art Deco building in Volunteer Park and founder Richard Fuller still attended to museum business from his wheelchair. Legendary artist Morris Graves might appear on the loading dock, and the young guard of Seattle’s art scene staffed the museum. Among them was Anne Focke, ’67, in the education department, who went on to organize Festival ’71—which morphed into Seattle’s long-running summer arts celebration, Bumbershoot—and and/or gallery, which evolved into Artech Fine Arts service and 911 Media Arts. Everything seemed possible in those heady days.

At home in the creative environment of the museum, Olson imagined a future for himself there—and that future was film. He was active in the local film scene, attending the 1970 jurying of prizewinners for the Bellevue Film Festival, which ran from 1967-1981. There he saw an experimental film called “The Grandmother” by a young artist named David Lynch. It was an extraordinary film that won second place that year, and the filmmaker’s name would stick in Olson’s memory. He soon started organizing film programs himself, checking out 16mm silent shorts and animated films from the library and screening them at the museum.

Then Focke invited Olson to program films for Festival ’71. He arranged for 11 hours of non-repeating films to be shown continuously. But Olson wanted more than the occasional gig. He knew other art museums had film programs and took the idea to SAM management: “Why aren’t we doing this?” he asked them. “I want to try.”

“Oh, how interesting a pair of hands can be. They can trick melody out of a piano keyboard. They can mold beauty out of a piece of common clay. They can bring life back to a dying child. Yeah, a pair of hands can do inconceivable good. Yet the same pair of hands can do terrible evil.”

Phantom Lady (1944)

In 1972, Olson was allowed to schedule films and show them in the museum auditorium—on his own time. But his break came that summer when he advertised a screening of the Frank Capra movie “Lost Horizon.” The 200-seat auditorium sold out and afterward, as people streamed out, an older man came up to Olson and emotionally shook his hand. He had seen the film about a fictional paradise called Shangri-La when it first came out in 1937, he said, and never thought he would be able to see it again. “Some kind of electricity went through me,” Olson recalls. “This was my calling.”

The powers that be at SAM were impressed, too. Not by the emotion, but by the sellout crowd. Olson got the go-ahead to start programming quarterly film series, to be shown once a week.

One of his early series focused on the work of director George Cukor. Among the films were “Camille” starring Greta Garbo, and “Little Women” and “The Philadelphia Story,” both with Katherine Hepburn. As Seattle Times critic Hartl pointed out when he previewed the series, Cukor was known as a great “women’s director” for his sensitivity to female roles. That’s exactly what attracted Olson.

He was also drawn to the dark emotions of the moody, cynical American crime and detective films of the 1940s and ’50s known as film noir. In 1977, Olson booked his first film noir series. “There’s something about that—people plotting at night and carrying through dark wishes—the eroticism, sudden death. … People loved it. I love it.”

Since then the film noir series has become an annual staple of Olson’s programming at SAM. Now in its 42nd year, it is the longest continuously running noir series, drawing a group of fanatical fans.

“Wherever you go, trouble finds you out.”

Point Blank (1967)

“That’s something I’ve gone to since my twenties,” says film and theater director Janice Findley, who teaches film history at Seattle Film Institute. “It’s a passionate group that comes, and most years it’s sold out within weeks. We live in this dark rainy place and you say, ‘OK, bring on the dark, bring on the winter, we are into film noir!’”

Film buffs like Findley admire Olson for searching out movies that can’t easily be found anywhere else. That’s because over the years, he has developed relationships with private collectors, film artists and studios that give him special access to rare material.

His acquaintance with the great British director Michael Powell (1905-1990)—acclaimed for classics like “The Red Shoes,” “A Matter of Life and Death” and “Black Narcissus”—is a case in point. Olson organized a series of Powell’s movies at SAM and was instrumental in bringing Powell to Seattle in 1989. He was dazzled to spend time with Powell and his wife, the renowned film editor Thelma Schoonmaker, while they were in town. Schoonmaker has edited Martin Scorsese’s films for the past 50 years, winning three Oscars for Best Film Editing (“Raging Bull,” “The Aviator” and “The Departed”). Powell died the following year, but Olson and Schoonmaker have remained friends.

In 1990, Olson read an article in The New York Times about a TV show called “Twin Peaks” that would soon revolutionize television. He looked over at his partner, Linda Bowers, and said: “I’m intrigued.” After the first episode, “We were just floored,” Olson says.

Two years later, he heard Lynch was back in Washington, making the movie “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.” Olson had kept up with Lynch’s career, from the cult hit “Eraserhead” on through “Elephant Man,” “Dune” and “Blue Velvet.” Olson identified with Lynch, from his Northwest roots to his complex nature: “He was an Eagle Scout with this Sunny Jim, Norman Rockwell demeanor who understood the darkest strain inside human beings.”

On a whim, Olson got in his car and drove up I-90 to the Snoqualmie movie set, skirted security, found a gap in the fence, and slipped in among the crew, unnoticed. Moments later, Lynch stepped through the same gap in the fence. Olson, amazed by it all, stayed until midnight and later wrote an account of the day’s filming, which he published in Film Comment. When he learned that Lynch liked his article, Olson decided to write a biography.

“Fate, or some mysterious force, can put the finger on you or me for no good reason at all.”

Detour (1945)

He published “David Lynch: Beautiful Dark” in 2008. During his research for the book, Olson and Bowers visited Lynch at his California compound. The pair had shared a fascination with “Twin Peaks” from the start. So when Bowers, a former executive director of Seattle Arts and Lectures, died of cancer in 2017, Olson continued working on the book about the TV series in her honor, feeling her spirit is part of it.

Olson’s role at SAM has expanded over the years. As film curator, he also coordinates film presentations to complement the museum’s current exhibitions, in addition to his quarterly film series. During the 25th year of the film noir series, Olson and then-contemporary art curator Trevor Fairbrother co-curated an exhibition “Night and the City: Homage to Film Noir.” It was so popular, Olson says, the exhibit was extended two extra months.

After decades of showing movies at SAM, Olson still searches out and books the films, writes the programs, and takes people’s tickets, greeting everyone as they enter the theater. And he still feels that old exhilaration when he sits down at the back of the auditorium to watch. “I’ll be in a room of people having a new experience,” he says. “That really pumps me up. And while I’m in the dream of the movie, I have the thought: I’m the agent that made this possible.”

Growing up in a household full of books and culture, Greg Olson surrounded himself with a variety of characters who touched the imagination.

Greg Olson stars as the hard-nosed antihero of the film noir genre. Dressed in a classic fedora and a cynical smile, this archetype is both a rough-necked seeker of justice and a sophisticated outsider who stays above the fray. He doesn’t trust the police. He trades blows with the bad guys. He really should know better than to trust the femme fatale.

A dangerous woman. Hard to ignore, impossible to forget. As likely to double-cross as any man. Played by Neomi Pantic.

Keeper of the cuffs. Bound by law, tempted by greed. A friend and a foe to the private eye. Played by Scott Milligan.

Works for somebody in the shadows. Plays rough, hits hard. He’ll be history by the second act. Played by Toby McAuliffe.

Director: Billy Wilder

Night-blooming jasmine, a shady man and woman, a big-money scheme. Smells like gun smoke when they kiss.

Director: Frank Borzage

The dark, haunting past has a death grip on a man, but his deep sense of alienation yields to love and compassion in this rare redemptive noir.

Director: Robert Siodmak

Brooding German Expressionist aesthetics meet American pulp fiction, and the atmosphere of film noir is born: a heroic woman, not the usual deadly one, walks shadowy streets on a mission to save her man.

Director: John Boorman

Noir goes corporate. A man double-crossed out of a lot of money comes to L.A. to even the score. He’s so cool he frosts palm trees; he’ll tear apart skyscrapers if he has to.

Director: Edgar G. Ulmer

A guy hitchhiking to L.A. to see his girlfriend encounters a wickedly dangerous woman—you never know when the abyss is going to open under your feet.