On a bookshelf in a Renton house sits a tattered blue dictionary, so worn that its binding has split into three pieces. Even though the volume clashes with the home’s otherwise crisp décor, Rochelle ThanhDung Nguyen would never part with it.

In the autumn of 1975, she was starting fifth grade at Briarwood Elementary School in Renton. The eldest of five siblings, she and her family had just arrived as refugees from Vietnam. “I felt like an outcast. School was a dreadful thing,” Rochelle recalls. “I didn’t know how to make friends and I was afraid of being teased.” She tearfully pleaded with her dad to return to Vietnam. Instead, Colin Chuong Huu Nguyen handed his daughter the blue dictionary. “This is your lifesaver,” he told her. “You learn with it and survive in this world.” Even with it, mastery of English required three long years and the support of two other teachers: “Sesame Street” and “Mister Rogers.”

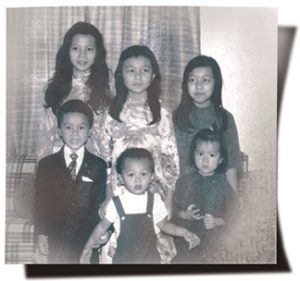

The Nguyen family in 1976. Clockwise from top left: Rochelle Thanh Dung, Ai-Lien, Thanh Quyen, Madeline Thanh Phuong, Evans, and Duc Quang.Family photo

The Nguyens fled South Vietnam on a military transport just a week before the Viet Cong rolled into Saigon in April 1975. They took nothing but the clothes on their backs—no food, toys or comforts from home. After a few days in Guam, they landed in Camp Pendleton near San Diego, Calif., where thousands of other evacuees waited in limbo. While anti-refugee demonstrators loudly protested their presence, the Nguyen family struggled to adjust to their new life: camping in a small tent, standing in long chow lines to eat unfamiliar food and suffering the challenges of unfamiliar latrines. “We didn’t know how we would be accepted by the American people, because the war was unpopular and American soldiers had died,” Rochelle recalls. “We worried our dad wouldn’t have a job that would provide for us. We worried about how our new life, culture and customs would be.”

Colin Chuong Huu Nguyen

Confounding the protestors’ short-sighted and worst assumptions, the Nguyen children would study with the discipline of a military unit, intent on grabbing the American dream by the collar. Inside 25 years, this uprooted family would boast two dentists, two engineers, an urban planner, and a successful entrepreneur in its ranks.

But that’s getting ahead of the story.

Ai-Lien, ’91

When the Nguyens huddled in their tent that spring 41 years ago, agonizing about the future, then-Gov. Dan Evans was hopping mad. After hearing California Gov. Jerry Brown state on national television that Vietnamese refugees were not welcome in California, he promptly dispatched staffer Ralph Munro to Camp Pendleton. “If you see Jerry Brown, you remind him what’s written at the foot of the Statue of Liberty,” insisted Evans. Munro issued an invitation to the refugees: “You’re welcome in Washington.” Evans called on the people of our state to open their hearts, homes and churches to the immigrants. By June 1, the Nguyens had arrived in the Edmonds home of their sponsors.

Duc Quang, ’95

Within a few short weeks, Chuong landed a job locally with the National Can Company. He and wife Xuan Hoa Thi Pham—pregnant with their sixth child—moved their brood to a rental home in the Rainier Valley. When their baby was born, to express their gratitude to the Washington governor, the couple named him Evans. “I wrote a letter congratulating them and conveyed my honor in having a namesake,” recalls Dan, ’48, ’49. “We stayed in contact by mail but I was pleased when I received an invitation from Evans to visit him at his school. I believe he was then in the first grade. From then on, we were in regular contact, which included a family luncheon at Christmas time, alternating between our home and theirs. We have been involved in school graduations, weddings, christenings, and holiday gatherings ever since. It has been a rewarding experience for Nancy and me and we are delighted with the success of this remarkable family.

Rochelle Thanh Dung, ’89

“The first three Nguyen children were valedictorians at Liberty High School in Renton,” the former governor recalls. “When it was Evans’ turn to graduate, I hadn’t received an invitation … They were reluctant to invite me because Evans wasn’t valedictorian. But of course, we went to his ceremony.”

Gov. Evans observes that his friends’ home had two shrines: one religious and the other to education. Over the years, the kids’ diplomas grew to cover an entire wall.

Madeline Thanh Phuong, ’96

The Nguyens’ academic success demonstrates a fierce tenacity in the face of incredible odds. The only Vietnamese in their classrooms and community, none of the kids spoke a word of English when they arrived for the first day of school. Madeline Thanh Phuong, who eventually went on to earn a B.A. in English, was initially placed in special-education classes because of her lack of language skills.

Then there were the cultural misunderstandings, including one instance where school personnel suspected that Chuong Huu Nguyen and Xuan Hoa Thi Pham were abusing their kids. “When we were sick, my parents would take a penny or quarter to rub on our backs to help stimulate the blood circulation,” explains Thanh Quyen, ’93, ’96. A traditional remedy for everything from colds to nausea, “coin rubbing” is considered a success when it produces prominent reddish marks that last a few days. “That is when bad chi comes out and balance is restored to the body,” Quyen says.

Evans, ’98

As the oldest child, Rochelle carried the heaviest burden. She was responsible for making sure her brothers and sisters studied hard and maintained their physical fitness every summer. She drilled them in handwriting, reading, spelling and math, and then had them running laps and playing badminton in their yard. “Other refugees had their kids selling hum bow or strawberry picking,” she says, “but my dad said he would rather work seven days a week, 12 hours a day than have anything take us away from our studying.”

Thanh Quyen, ’93

All that effort paid off. All six Nguyen children went on to earn degrees from the UW, with Dan and Nancy Evans always on hand to applaud their achievements. “When I graduated from the UW, Gov. Evans was a regent. As I got my diploma,” says Evans, ’98, who studied mechanical engineering, “he came across the stage and shook my hand.”

The Nguyens and the Evans celebrate their friendship with a yearly dinner that continues to expand as the new grandchildren arrive on the scene. (Dan and Nancy have nine, while the Nguyens now have 12.) The two men share their enjoyment of family and the way history brought them together, although they come from different worlds and from different cultures.

Washington’s tradition of open doors and hearts made the Nguyen story possible and shows how we can help other refugees fleeing dangerous situations in Syria, Afghanistan and other war-torn countries. Now it’s up to a new generation to carry that torch forward and build on that legacy.