When Dad ran

for president

When Dad ran

for president

When Dad ran

for president

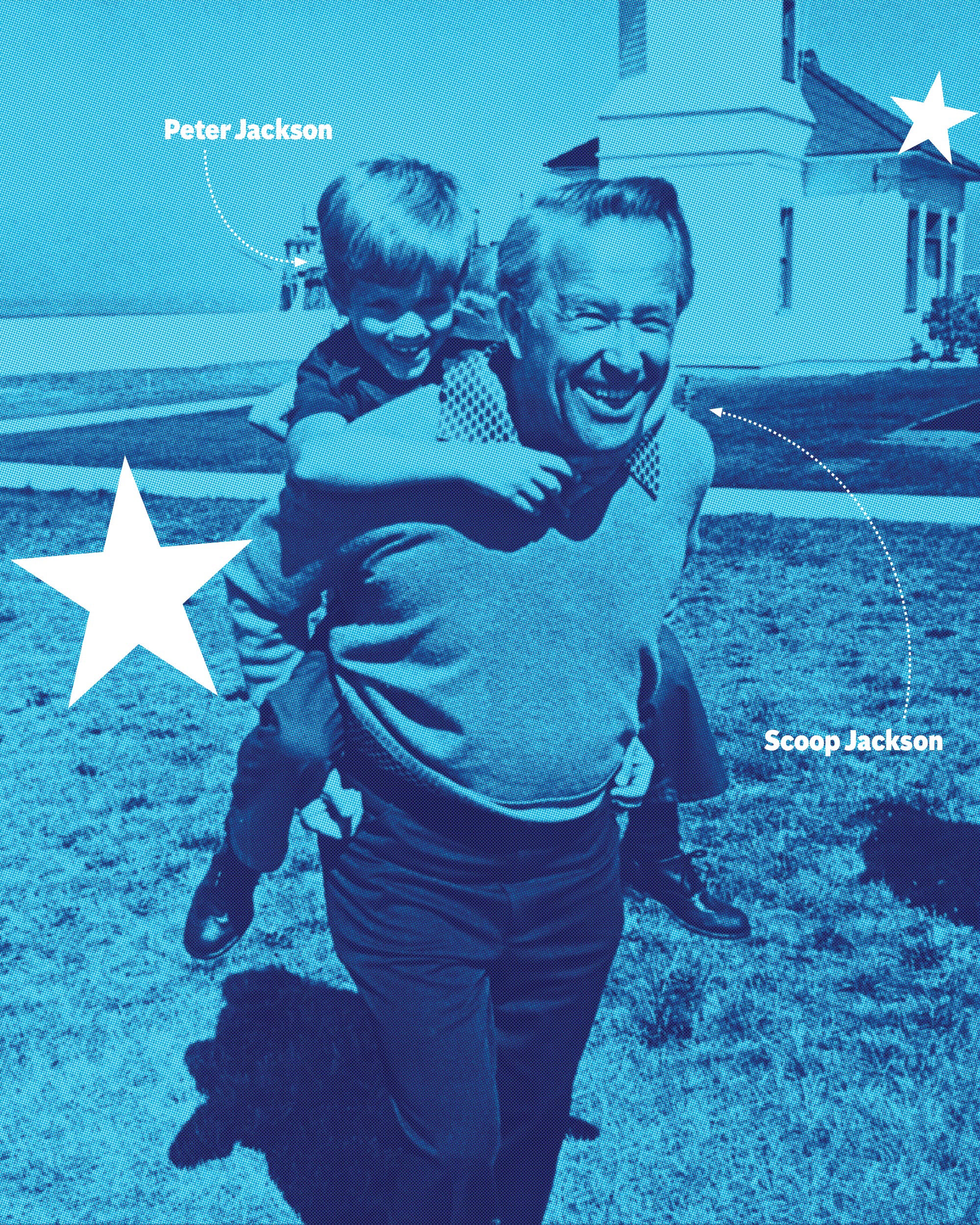

In 1972 and 1976, Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson was a candidate for the highest office in the land. I was along for the ride.

Story by Peter Jackson | Photo by Greg Gilbert | September 2019

Politics is an unforgiving beast, but there are occasions when ambition and public service coalesce, and a Husky begins to mutter to herself, “I could be president of the United States. I mean, why not me?”

My late father, Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson, ’35, made two failed bids for president of the United States, in 1972 and 1976. Both tries illustrate the vagaries of timing, kismet, and history. But his confidence and call to run incubated during his years at the UW.

“In many ways, Jackson was the quintessential Washington politician: A square-headed, stubborn Scandinavian from Everett, he lacked color but worked hard,” writes Knute Berger in the Seattle Weekly. “He was clean-living, virtually scandal-free throughout his decade in politics. He wore off-the-rack suits, was a poor public speaker, and came off as a pretty nice, if relentlessly dull guy.”

There’s that word: Dull, which latched onto Scoop like flypaper. His friend, Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, called him the last Cold War liberal. But to be cast as the last anything wasn’t helpful, politically speaking.

There have been other Huskies who gave the nation’s highest office a real gander. Former Gov. and Sen. Dan Evans, ’48, ’49, was a serious contender for vice president in 1968 and 1976 and would have been a formidable candidate for president in 1976. And the recent candidacy of Gov. Jay Inslee, ’73, crystalizes the potential of a presidential bid. Even if things fall apart, there’s the promise of elevating a broader message such as climate change or human rights.

My dad had been a popular member of the U.S. Senate and the House, and he assumed that his popularity would find expression nationwide. In the much smaller, less fractured media environment of the 1960s and ’70s, one appearance on “The Dinah Shore Show” could make you a household name. Scoop made that one appearance, along with semi-regular interviews on “Meet the Press” and “Face the Nation.”

He performed decently in 1972, racking up the second-highest number of delegates, but never winning a primary and ultimately losing to Sen. George McGovern. In 1976, he started strong, winning the Massachusetts and New York primaries, but he lost to Jimmy Carter in Pennsylvania.

Aspects of those campaigns were as austere as they were cornball. My mom spent a couple days in 1976 visiting towns in Massachusetts that shared the name of towns in Washington (think “Everett, Massachusetts” and “Bellingham, Massachusetts”). The grand strategy behind it was a mystery.

Most voters recognized Scoop. Wasn’t he the IRS commissioner? Or the self-assured spokesman in that life-insurance commercial?

My perspective is warped, of course. As a child, I was awed by the mayhem of parades and protests, and I schemed to get into the act. In 1972, at age six, I was trotted out to recite the names of every U.S. president in chronological order. After Richard Nixon, I would pause dramatically, and mumble my father’s name, as if asking a question: Henry M. Jackson?

Supporters were not exactly sure how to respond.

In both the 1976 and 1972 races, Scoop highlighted his work as the longest-serving chairman of the U.S. Senate Interior Committee. He had authored the National Environmental Policy Act and helped shepherd the North Cascades National Park Act. But that angle didn’t square with his reputation as a Cold Warrior. It’s what the political class call “shaping the narrative.” (Note to future Huskies hankering to run for president: Shaping the narrative doesn’t work).

“Jackson isn’t a doomsday man. He has faith in the people and the system. He wants to make it work. … He always tells you where he stands. He’s a quiet, studious, hard-working man. He puts in 18-hour days. But once he’s made up his mind, he fights for what he believes.”

–A 1972 Campaign Brochure

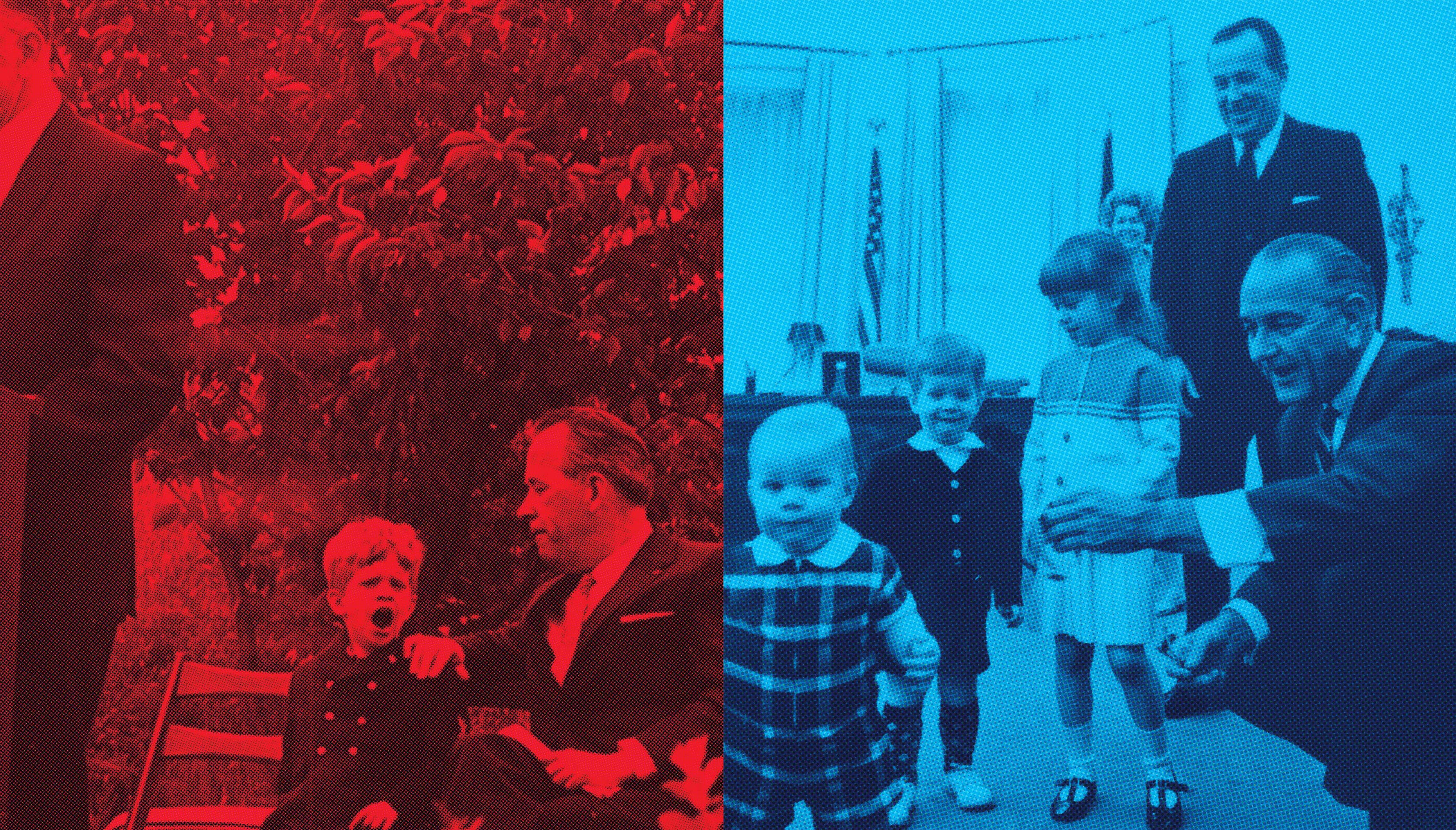

LEFT: THE AUTHOR, AT 6 YEARS OLD, PAYS ATTENTION DURING A SPEECH BY Washigton Lt. Gov. John Cherberg in 1972. RIGHT: THE AUTHOR, A FEW YEARS EARLIER AT CENTER, STANDS UP TO PRESIDENT LYNDON JOHNSON.

Can you harmonize support for the Vietnam War and the environment? Younger voters were incredulous, while labor unions and working-class voters were receptive.

Looking east out the drunken wave of window glass of his childhood home, my dad would point and name the mountains north to south, as if taking a test: Three Fingers, Pilchuck, Glacier, Big Four, Sloan Peak. A day when pewter clouds don’t curtain the horizon. Don’t be fooled, he said, Glacier Peak looks like a bump, but it’s farther east, and twice the height of Pilchuck. And it’s a volcano.

“Someday it will erupt and all hell will break loose,” he said.

Listen to Scoop responding to questions on the 1972 campaign trail:

Scoop’s political consciousness was shaped at the UW, where he cleaned dishes in a sorority kitchen. It was the Great Depression, when unemployment in Washington hovered around 25 percent. At the end of dinner, families zigzagged behind the sorority house, pleading for table scraps. People throughout the Pacific Northwest were suffering, with students and the homeless raiding local Safeways. It was a formative time, and Scoop quickly became a New Deal Democrat.

Jackson was a dedicated public servant, hopping from Snohomish County Prosecuting Attorney to, at age 28, election as the youngest member of the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1952, his friend and media adviser Jerry Hoeck, ’42, ’44, enlisted a commercial artist to paint a billboard of a conservatively dressed Scoop posed behind a Senate desk chair. It was the 1950s version of Photoshop, a ploy to make a youthful forty-year-old appear a decade older, and it worked.

In 1954, Scoop had made a name for himself, challenging the demagogic Sen. Joe McCarthy. By 1960, he was appointed chair of the Democratic National Committee, a consolation prize for not getting tapped to be JFK’s vice-presidential pick. Scoop was, at age 49, still a bachelor and bachelors weren’t presidential material.

My dad waited to get married. And he waited. “I was prosecuting attorney at 26 and I got overly involved in my work,” he told Women’s Wear Daily. “When people would ask, ‘Why aren’t you married?’ I would say, ‘I’m just too busy looking after the public interest.’ That’s a good joke, if nothing else.”

Scoop was the child of Norwegian immigrants, the youngest of five. As a boy growing up in Everett, he watched a Fourth of July parade that included an actor dressed like an American doughboy, pitchforking a caricature of Kaiser Wilhelm II. It was a boyhood scored by circular saws and the tattoo of shingle mills.

Life was cleaved by sharp corners, with children contracting deadly diseases such as small pox. Scoop had survived small pox, but two of his childhood friends did not.

He thought of the world as an unquiet, often violent place.

“The Russians are like the burglar walking down the hall, checking doorknobs. That one unlocked doorknob, and you’re done.”

Circle up my late mother’s back staircase and you’ll find where memorabilia sits on the landing like a museum diorama. There is my dad’s pioneer-ish baby carriage, fit together like a Wright Brothers’ wing. There is his Boy Scout hat, a sepia-toned Boy Scout pic, his American Flyer Lines train set. There are toddler blocks.

His message likely was too centrist, the establishment candidate in an anti-establishment era. “One thing I’ve learned is that whenever there is a crisis or a problem in this country, there is a tendency for both the right and the left to go off the deep end.”

A Husky law degree was a plus; hailing from a small, Western state in the far edge of the the lower 48, not so much.

Picture a Northwest family living in the White House with an Alaskan malamute named Dubs III. Or a purple and gold White House State Dinner.

Someday, perhaps.

* * *

Henry M. Jackson Collection at the University of Washington Libraries

Want to learn more about Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson, ’35, one of the most prominent alumni ever to serve in the House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate? The University Libraries is the place for you. The Henry M. Jackson Collection encompasses his papers, photographs and sound recordings beginning with his House career that started in 1941. His Congressional career spanned 43 years and nine presidents. Check out the digital collection. The full Jackson collection, as well as the collections of many other prominent alumni, are held by the Libraries’ Special Collections.