In 1990 Richard Gonzalez got his Ph.D. from Stanford and went looking for a job. Harvard and UCLA courted the new psychology professor, but he rejected their offers and came to the UW instead.

“At that time it was an up and coming department. It was growing. It seemed to have lots of revenue, was hiring people and was very exciting. I intended to spend my career here,” he recalls.

But budgetary pressures soon followed. When Gonzalez tried to integrate the computer into his classroom, there was no funding. “I tried to do it on my own time, but if you don’t have the right equipment, it is very difficult,” he says.

Then came weak research support and little clerical help. “We actually got charged for paper clips. It was ridiculous. In the business world, this doesn’t happen.” The pay situation was also disturbing. The Legislature froze salaries in one two-year period and then only granted sporadic raises. With inflation, “you were always falling behind,” he notes.

Still, Gonzalez wasn’t too interested when the University of Michigan came calling in 1997. “I really didn’t take them too seriously at first. I felt things were going to turn around here.”

But after a visit to Ann Arbor, Gonzalez thought twice about Michigan. “They were going to double my resources, double the size of my lab and give me a 40 percent pay increase.” Due to his sabbatical leave, Gonzalez was committed to either teach that fall at the UW or pay back his salary. Michigan offered to cover whatever he owed Washington.

The UW tried to keep him. “Rich was an all-around professor,” recalls Psychology Chair Michael Beecher. Not only was Gonzalez an excellent quantitative psychologist, but he was also a superb teacher. “He was extremely popular with the students and that was unusual in that he taught statistics,” Beecher says.

“It's the worst it's ever been, and I've been here for 24 years.”

Steven Olswang, vice provost

Gonzalez struggled with his decision for months. “It was like getting a divorce,” he says. One factor was the state’s 1997-99 budget. “When I started to hear what the state budget was like for higher education, it made a difference. But it was not one single thing. I realized I’d be much happier here (at Michigan) professionally.”

In September 1997, Gonzalez packed his bags and moved to Ann Arbor. A year later, he says he has no regrets. “It’s like heaven here,” he declares. “I’ve got the funding to develop my teaching ideas. The University is giving me staff to help with computer programming and a computer lab.

“At Michigan, there’s money to do actual work. The attitude is, ‘If it’s something important that you want to do, we’ll make it happen.’ ”

Meanwhile, back at the UW, Gonzalez’s decision was a blow to morale. A year later, Psychology Chair Beecher is still looking for a replacement and worries that another young faculty member may also leave for Michigan.

The University of Michigan isn’t the only school that is knocking on Washington’s doors. Illinois, Stanford, Northwestern, Cal-Berkeley-over the last three years most of the top names in American universities have tried to raid UW departments or lure away potential new faculty.

The most notorious case took place last spring. Several schools targeted History Professor Richard White, a MacArthur Fellow who is a leading authority on the history of the American West. After spurning a proposal from Harvard, he accepted an offer from Stanford despite the UW’s promise to match its bid.

White’s departure sent off alarm bells. Seattle Times Guest Columnist David Brewster called it “a terrible loss. White is perhaps the biggest star in the humanities that the UW possesses.”

These departures confirmed what most UW insiders already feared. The brain drain at the UW-a scourge of the 1980s-is back. It’s not just history and psychology that are suffering. Faculty are leaving music, mathematics, finance, public health-almost every sector is feeling the pinch.

“It’s the worst it’s ever been, and I’ve been here for 24 years,” says Steven Olswang, the vice provost who deals with faculty recruiting and salary issues.

“It’s worse now,” adds the chair of the Faculty Senate, Education Professor Ted Kaltsounis. “In the 1980s the financial situation was not as good for the state. There was some understanding. Now people see the state prospering and we’re still going down. That makes it worse for morale.”

“I’ve been here for 15 years and it’s incredibly depressing,” says Economics Chair Richard Startz, who found it took three years to fill two openings in his department. “It’s worse than the mid-80s.”

Plenty of numbers confirm their case. The gap between the average UW salary and that of comparable institutions is widening. At 4 percent in 1994, the gap is now at 14.3 percent with little sign of a downturn.

There are other statistics that track the widening exodus. In 1997, the Legislature set aside $2.4 million to keep faculty from leaving and to win battles in recruiting wars. The fund was supposed to last for two years-but after 12 months it was exhausted.

“The differential is so high now between current salaries and offers from other institutions,” says Olswang. “It can range from $30,000 to $50,000. Sometimes it’s double what they are making here, sometimes more than double. One professor went from $70,000 to $160,000.”

And in cases where the UW is able to make a counteroffer, the rejection rate is growing. In 1995-96 only 6.1 percent rejected the UW’s attempts to keep them. In 1996-97 that rate rose to 15.5 percent. Last academic year almost a quarter (23.2 percent) left despite UW bids to keep them. Olswang thinks it can only get worse. “We will lose 40 to 50 faculty this year,” he predicts.

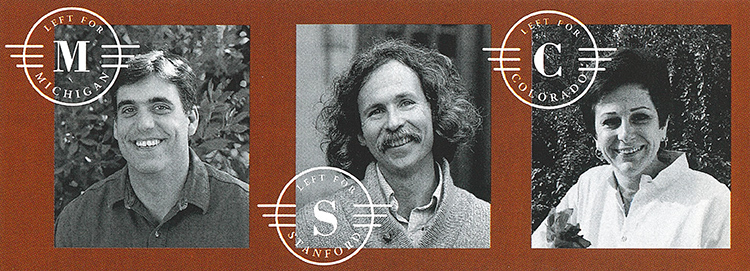

From left: Former psychology professor Richard Gonzalez; former history professor Richard White; and former music professor Joan Catoni Conlon.

There are plenty of stories behind these numbers:

- Mathematician Richard Bass had been at the UW for 21 years. When the University of Connecticut offered him a salary 60 percent higher than what he was making at the UW, he left. “I’ve been kicking myself that I didn’t look sooner,” he admits.

- Music Professor Joan Catoni Conlon, once head of the UW’s choral program, taught at the UW for 19 years. She touched the lives of hundreds of students in the University Chorale. The University of Colorado offered her increased research support and a 30 percent pay hike. “When I saw what my salary was going to be, when I saw there were more resources for research activity, library resources and support from the graduate school, I decided to take it,” she says.

- Accounting Professor Mark Peecher was a dean’s dream. “He was a budding star, potentially a superstar,” recalls Business School Dean Bill Bradford. “He was doing good work in a difficult area. He got great student evaluations. He was good in the classroom and good in research.” Peecher left this fall when the University of Illinois offered him a $40,000 pay hike. “We knew we couldn’t even come close to that,” Bradford says.

“We’ve lost candidates to Cornell, Pittsburgh and Michigan,” Bradford says of his recruiting efforts. “The word is out,” he laments. “It’s been a difficult year and it’s going to get worse.”

The University is fighting its brain drain, but since the state sets overall salary increases, much is beyond the University’s control. President Richard L. McCormick has made faculty and staff salary raises the number one priority in the next legislative session, which begins in January.

The University of Washington, along with all other four-year state colleges and universities, is asking for a 4.5 percent pay increase in each year of the next biennium. The state’s share of the UW increase would total $41 million, with the UW adding $9 million from its own funds. Salaries would not rise across the board; increases would be based on merit.

“Faculty and staff are the foundation of this institution’s quality and we must do everything we can to maintain that quality,” McCormick told the regents in September. “It is in the best long-term interests of the state to invest now in sustaining the excellence of this institution, rather than letting that quality erode and trying to repair the damage later.”

The regents agreed, and to emphasize the gravity of the pay situation, they froze the President’s salary at its current level. “We need to dramatize in every way possible the serious and precarious position we find ourselves in with respect to faculty salaries,” said Board of Regents President Shelly Yapp.

But the drama hasn’t moved many legislators so far. Rep. Tom Huff (R-Gig Harbor, pictured at left), who is the current chair of the House Appropriations Committee, is cool to any talk about a crisis at the UW. “There is a brain drain at every level. Private industry is having a tough time holding onto its all-stars,” he says.

While he agrees there is a pay gap between UW faculty and peer universities, he adds that “money isn’t the only reason that people leave. There are a lot of different reasons.”

The University knows it faces a challenge in Olympia. “There is much more skepticism about the role of public institutions broadly,” says Associate Vice President for University Relations Sheral Burkey, the UW’s spokesperson in the state capital. “The interest is in cutting back on state spending rather than investing in important state resources such as higher education.”

Vice Provost Olswang, who has testified to lawmakers many times on faculty salary issues, shakes his head. “Somehow they view us as just another state agency,” he laments. “Would Boeing underpay its CEO so he or she could be stolen away by Airbus?”

Like Boeing, the UW is a vital part of the Washington economy. A 1997 economic impact study found that the UW attracted more than half a billion dollars from out-of-state sources-new money added to the state’s economy which generates new jobs.

The same study found that UW’s $1.6 billion in direct expenditures generated an additional $2.8 billion in economic activity. The total UW economic impact on the U.S. economy amounts to $4.4 billion, with $3.6 billion occurring in Washington state.

More than 100 Washington companies have been born out of UW research, including 27 in 1997 alone. Discoveries by UW faculty have helped spawn everything from Optiva, which makes the Sonicare toothbrush, to biotech companies such as PathoGenesis and ZymoGenetics. Nobel Prize-winning faculty include a pioneer in bone marrow transplants and a physicist who was able to trap and hold a single electron.

Harder to measure is the public service UW faculty devote to the state. From the Olympic Natural Resources Center based in Forks to the Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic near Yakima, every corner of Washington is touched by UW faculty.

An inventory of efforts to improve K-12 education found that nearly 100 UW departments have about 150 programs in the state. One shining example is a science education project targeting 1,400 teachers at 70 Seattle elementary schools. Funded with $4.25 million from the National Science Foundation, the effort was the brainchild of Leroy Hood, chair of the Department of Molecular Biotechnology and a leader in research to decipher the human genome.

UW officials shudder at the thought of Hood leaving as historian Richard White did. If the brain drain continues, its impact on the community can only get worse. “You can’t continue to expect the high level of contributions at these salary levels. You can’t sustain it,” warns Burkey.

“Basically, you can’t keep good people if you can’t pay them enough,” says Psychology Chair Beecher. “The word is out that this is a good school to raid.”

“People should be rewarded for doing a good job,” Rep. Huff responds. The current appropriations chair adds that he might consider some kind of retention fund and perhaps a sliding scale of salary raises based on performance. But he notes that in the last state budget, salary increases for faculty were greater than for any other state employee group. And he wonders about under-performing faculty and what mechanisms are in place to increase their productivity or remove them. “In private industry we would never tolerate that,” he declares.

UW officials know that even if the Legislature grants a 4.5 percent increase in each year of the budget, it won’t wipe out the pay gap or stop the brain drain cold. But an increase will boost faculty morale and probably stop many from looking elsewhere. “We need a commitment, a goal to fix the inequities,” says Olswang.

The alternatives are not pretty. “We’re going to lose more people. In addition, recruitment is going to become even more difficult. We’re going to have to hire second-rate people. We will become a mediocre university,” warns Faculty Senate Chair Kaltsounis.

Although no one wants to face more department closures, the UW may have no choice. “To maintain quality we may have to do fewer things for fewer people,” warns Olswang. “The institution would have to look at ways to protect its high quality areas,” adds Burkey. “We would not be as comprehensive an institution as we currently are.”

But it doesn’t have to be that way, Gonzalez maintains. “It’s not too late,” says the former UW professor. “Washington has the potential to be just as good or better than Michigan. It’s a matter of turning things around.”

Beyond the brain drain: other UW budget priorities

In addition to its top priority of a faculty and staff pay increase, the UW has three other major requests for the 1999 legislative session.

* Enrollment Increases: The UW is seeking an additional 1,600 full-time students at its three campuses during 1999-2001. At Seattle, 500 full-time undergraduate slots would expand high-demand majors such as computer science, social welfare and civil engineering. About 400 spaces for graduate students would also open up. Bothell would receive 240 undergraduate slots and 60 graduate-level spaces. Much of the growth would be in liberal studies, business and software systems. Tacoma is seeking 300 extra undergraduate spaces for business, arts and sciences, and information technology, as well as 100 graduate-level spaces. Total cost: $29 million.

* Technology Initiatives: The state’s two research universities-UW and WSU-would launch an Advanced Technology Research Initiative. Special funds would establish faculty “clusters” which would collaborate with the private sector in areas such as micro-electronics, computer multimedia software or new drugs. Other UW technology initiatives would integrate computer technology into more academic programs and increase student participation in research and public service. Total cost: $31 million.

* Capital Projects: There are four major projects in the UW request. The state’s share of a new Law School Building would total $44 million, with an additional $23 million in donated funds for the project, located in a parking lot south of the Burke Museum. About $45 million is needed for a complete renovation of Suzzallo Library to bring it up to code, make it accessible and strengthen it against earthquakes. The UW Bothell campus is seeking $46 million to carryout a second construction phase at its site near the I-405/SR 522 interchange. UW Bothell permanent campus is scheduled to open in the fall of 2000. The UW Tacoma campus, which opened in 1997, is already full. To keep the growth of the campus on schedule as enrollments increase, the UW is seeking about $77 million in design and construction costs for the second phase of its campus plan.