Genetics Professor Lee Hartwell wins Nobel Prize in medicine

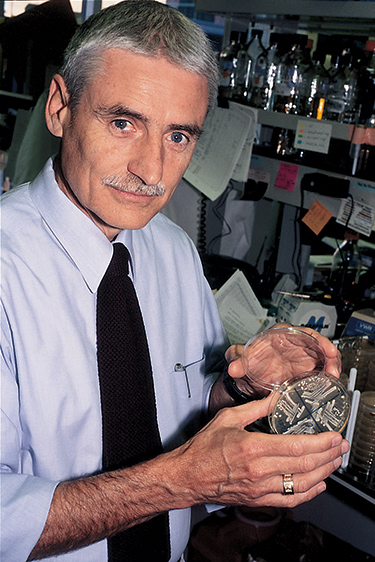

Lee Hartwell

UW Genetics Professor Lee Hartwell won the 2001 Nobel Prize in Medicine/Physiology for his basic research on cell division, the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm announced Oct. 8. Hartwell, who is also president and director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, shared the prize with Paul Nurse and Timothy Hunt, both of the Imperial Cancer Research Fund in London.

“I am very pleased to be honored,” Hartwell said at an Oct. 8 press conference. “But it is a little bit hard to be too celebratory at this time,” he added, referring to military action in Afghanistan that had been launched the night before.

“He is the fifth UW faculty member to receive a Nobel Prize, and most of his research was conducted at the University of Washington. Of this, we are very, very proud,” said President Richard L. McCormick. With Hartwell’s honor, the UW community now has eight Nobel laureates—five faculty and three alumni (see chart below).

By studying common brewer’s yeast, Hartwell made crucial contributions to understanding the universal operating system of life—how cells divide.

“To understand cancer, you have to understand basic cell division,” explained Radiation Oncology Professor Mark Groudine, a close colleague of Hartwell.

Hartwell found that there is a set of “checkpoints” that control cell division. As it divides, each cell checks to make sure everything is proceeding smoothly before starting the next step in the process, like a conductor rehearsing a symphony orchestra. If something is wrong, the cell stops the process and starts over, just as a conductor would stop the orchestra if the violins came in at the wrong moment.

When the checkpoints aren’t working, the cells get out of tune. “The genes that control the checkpoints often are mutated in cancer cells,” Groudine explained. He says Hartwell’s work, along with the breakthroughs by prize-winners Nurse and Hunt, will lead to new therapies that could combat cancer.

When Hartwell came to the UW in 1968, he decided to study yeast cells because they are simpler and easier to manipulate than human cells. At the time, Hartwell recalled, this was “a fairly risky assumption,” as he was the only person looking at yeast cells to find genes that control cell development.

Working in laboratories on the first floor of the Health Sciences Center’s J-Wing, Hartwell grew yeast in lab dishes. “The most sophisticated technology we used at the time was a toothpick,” he recalled. He credits then Genetics Chair Herschel Roman with pushing him along his research path.

“Many of us had no confidence that yeast would provide information on humans, but it turned out to be true, Herschel Roman being one of them who had the confidence,” Hartwell said.

Hartwell, 62, grew up in Southern California and admits he was a C-average student in high school until a physics teacher inspired him to study science. After two years at a local junior college, he transferred to Caltech, where he earned a B.S. in 1961. He earned his Ph.D. from MIT in 1964.

Genetics Chair Roman recruited Hartwell while the future laureate was working at the University of California, Irvine. He joined the UW faculty in 1968. He has been a full professor of genetics since 1973, and in 1996 he joined the faculty of the Hutchinson Center. One year later he became its president and director.

He will share $943,000 with his fellow prize-winners. The researchers will receive the award on Dec. 10, the 100th anniversary of the death of Alfred Nobel, after whom the award is named.