A tribute to John Hartl, ’67, Seattle’s greatest movie critic

Famed movie critic John Hartl, who spent decades at The Seattle Times, had a thoughtful eye, an unusually high IQ and an encyclopedic knowledge of film. His longtime friend and colleague Sheila Farr recalls their times together.

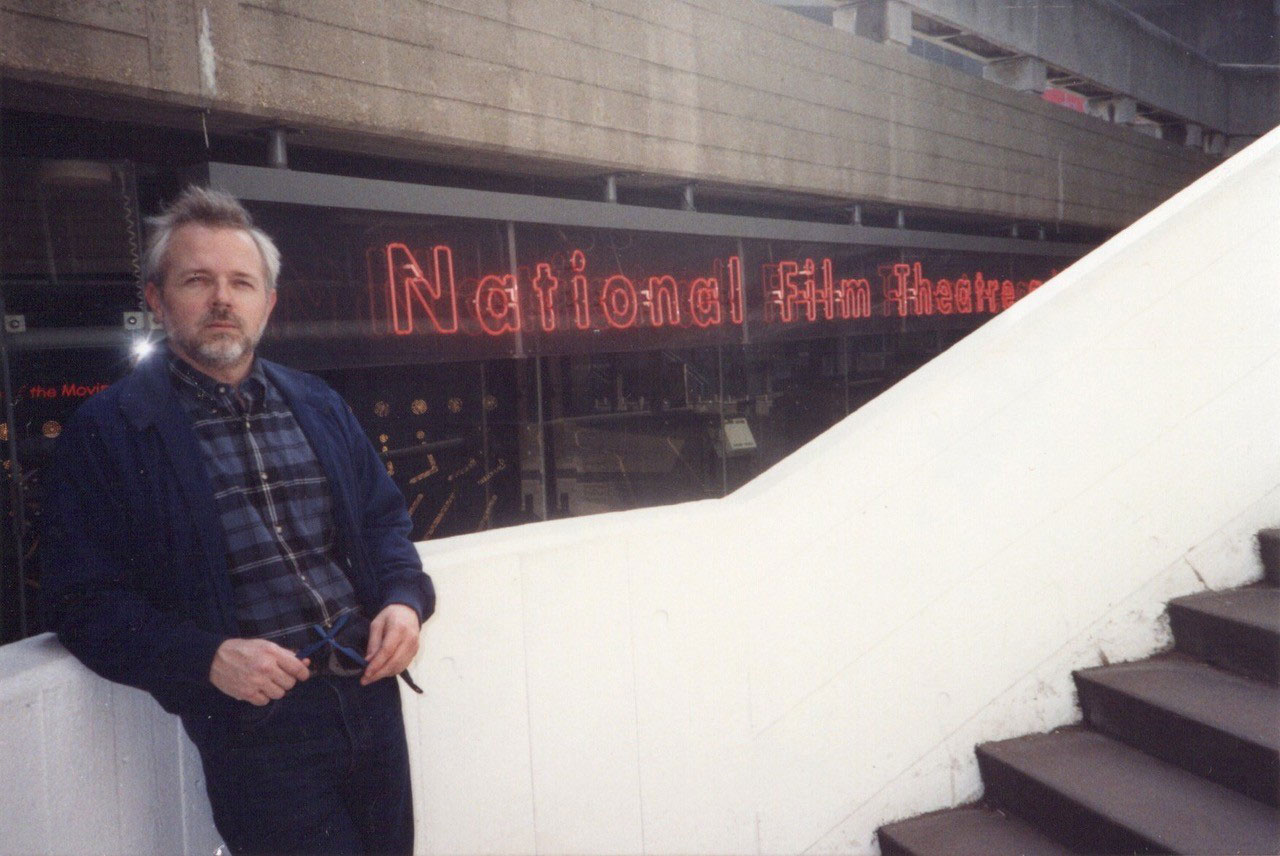

John Hartl at the British Film Institute in London. Courtesy of Michael Upchurch.

John Hartl was still an undergraduate at the University of Washington when he began his career as a film critic for The Seattle Times. For the next half century, he would guide and instruct readers: helping us understand, in ways we might not have been able to articulate, why a film worked – or crashed.

Even after he took an early retirement from the Times in 2001, disillusioned with newspaper life and an onslaught of trivial movies, he couldn’t give up. He kept writing freelance reviews until the progression of Lewy body dementia stopped him a few years ago. He was 76 when he died on June 3, still enthralled by movies.

It’s rare for someone so young to come to a job fully formed. But even in his earliest reviews, John’s voice was utterly assured and unaffected. He could sum up a performance with a few choice words. Of Rock Hudson in the 1966 movie “Blindfold,” he wrote: “Hudson didn’t act, he behaved.” And of Hudson’s co-star Claudia Cardinale: “Her performance consists mostly of changing from one skin-tight costume to another and then getting her sweater wet.”

Humorous in an understated way, sometimes tart but blunt when he needed to be, John was able to place films in context of the times, in the history of cinema and within the work of individual directors and actors — all when he was in his early 20s.

That’s because he had been studying movies since childhood. While still in elementary school, John made a weekly movie bulletin board for the family, featuring everything playing in their small town of Othello, Washington, and at the nearby theaters in Quincy and Wenatchee. According to his sister Mary, John would paste in clips from reviews, publicity photos, and his own remarks and illustrations. Then, just for himself, John had another bulletin board. That’s where he’d post the films showing in his imaginary movie house: “Citizen Kane,” sci-fi and horror movies, Hollywood classics, the great silent films of Chaplin and Keaton. In John’s ideal movie house, there was always a double feature.

When John got a paper route to earn money, he began collecting – and making – 8mm and 16 mm movies. He would entertain the neighborhood kids in the garage, hanging a sheet for a screen, selling popcorn and homemade root beer. At the age of 16, he won first place in a Portland newspaper’s Oscar awards contest, choosing the winner in nine out of ten categories. (He got free movie passes for a year – a real bonanza.) Did he already know that newspapers and movies would be his life?

When I first encountered John, I was 18, studying ballet at UW by day and working nights at the newly opened Harvard Exit Theater on Capitol Hill. Having John arrive at the theater was like a visit from royalty. He looked so young, yet, with his reviews, he had the power to make crowds appear. I never could have imagined we would one day be colleagues. But some 30 years later, when I was hired as The Times visual art critic, there we were, sitting a few desks apart. We quickly became friends.

The first time I invited John and his partner (later husband) the writer Michael Upchurch, to dinner, I realized how unusual John was. A group of us were sitting around the table, drinking wine and telling stories. John was quiet. When I glanced across the table at him, he was looking right at me. John didn’t shift his gaze like most people would when caught staring—because he wasn’t staring. He was watching the dinner party like he was at the cinema, taking it all in. That was his approach to life. When he did have something to say, it was astute— and people listened.

And then there was John’s prodigious memory. If you mentioned some movie you’d seen decades ago, he could tell you the date it was made, who directed it, the actors who played in it, where he first saw it, what Academy Awards it won or should have, and maybe an anecdote about his interview with the lead. Chances are he had a copy of the film, too, maybe in multiple formats, in his vast library – and would suggest a night to watch it together. John’s sister Beth remembers being a bit awestruck early in life by her older brother’s soaring IQ, in the 140 range: “We always knew he was different.”

It’s true. There was no one like John. With all he had going for him, his modesty and kindness stood out. I never heard him say anything derogatory about other writers— colleagues or competitors— even when he completely disagreed with their views. He was generous with his knowledge and his respect — and, after he died, with his body, too. Eager to help others, he arranged to donate brain tissue to UW for neurological research. John Hartl was that rare creature: a gifted critic and a benevolent presence. Without him, the Seattle movie scene has lost some of its glow.

Sheila Farr is an author and arts writer. She served as the visual art critic for The Seattle Times from 2000 until 2009.