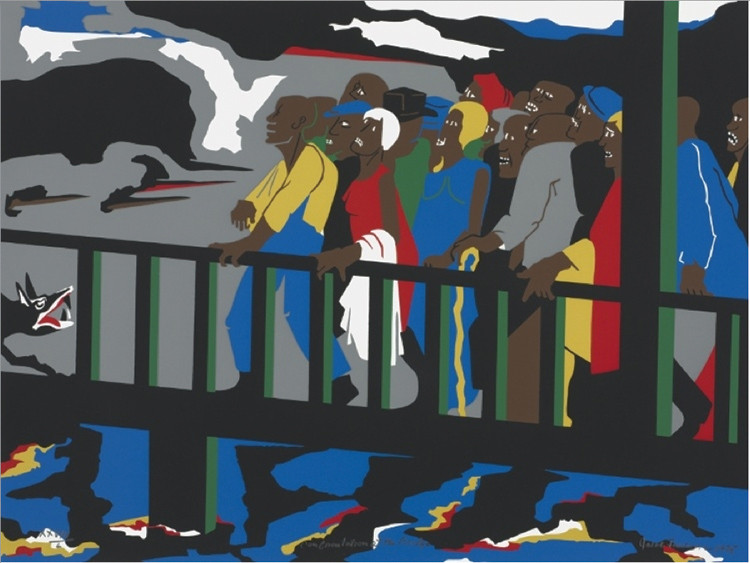

I, too, am America

Confrontation at the Bridge—Created by artist Jacob Lawrence ten years after “Bloody Sunday” when police attacked civil rights demonstrators at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Lawrence produced the print just a few years after he moved to Washington to join the faculty at the UW School of Art.

The first time I visited the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, I was swept with grief.

It was the first point during our UW-led Civil Rights pilgrimage where we faced the reality that the price of being black had been paid with innocent lives. These were not lives at the forefront of the struggle, but little girls who were simply changing into their choir robes for Sunday service.

Aida Solomon

We entered through a side door of the brick building, and formed a line down the stairs to the basement. As I stood in front of a portrait of the four children who were killed in the 1963 bombing, I realized that origin or ethnicity didn’t matter; if you were black, you were the target. At the age of 22, this is what I confronted. It was here that I realized what I have been building toward all through college.

Martin stood up, Rosa sat down. That was pretty much all the black history we were taught in grade school. Growing up in North Seattle, I was often the only black student in my class. At the same time, I never identified as African American or black. My parents emigrated from Ethiopia and brought with them a strong identity rooted in their values, traditions, beliefs and culture. My brothers and I were always told to be proud of our heritage, to be proud that our country was never colonized, that we were from the region that birthed civilization. But as a teenager, I really didn’t know how this would help me figure out who I was supposed to be in America.

My friends reminded me that I wasn’t black enough to be black.

I didn’t speak Amharic fluently, so I wasn’t Ethiopian enough. And I wasn’t as light as my white friends. I never could find myself fitting into anything. I came to the University of Washington intending to use the school’s vast resources for studying abroad. Instead, I made my own plan and traveled to Ethiopia for a quarter, building a public relations internship at Ethiopian Airlines around my interest in communication and media. After this amazing experience, I was convinced that I needed to move to Ethiopia for an extended period of time to address the negative preconceptions portrayed in western media. I believed that, in my own way, I could change the way we see this nation and other “Third World” countries that are similarly stereotyped. I had my plan: graduate and move to Ethiopia.

But early in my junior year, I learned about a Civil Rights pilgrimage to the American South with a group of alumni, students and faculty from Seattle. I jumped at the chance to experience another part of the United States and to learn from people who actually participated in the Civil Rights movement. Eight days on a bus driving through Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama and Tennessee was overwhelming, but in the best way. We were consumed with history we didn’t even know existed, getting to see these significant places and meeting people who had endured the most dehumanizing experiences and who were still standing strong.

It did something unexpected to me. It made me proud to be an American. Prior to this, I thought that meant being proud of our forefathers and the founding principles of this nation. But how could I be proud of a nation that institutionally exploited and discriminated against people who looked like me? Fortunately, I found a new meaning: standing for justice, equality, change and difference. I was so moved by my experience on the pilgrimage that I knew my relationship with the South couldn’t stop there. I applied to be a mentor at a summer youth institute at the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi. I wanted a different perspective of American life in a place so much closer to our nation’s traumatic Civil Rights past than Seattle.

I was really nervous to work with high schoolers. I kept thinking, “I’m this Ethiopian girl from Seattle. How could I connect with these kids?” But it didn’t take long. The students gave me a southern name, Aida Belle, and embraced me for who I was. I learned about their lives as Southerners and how aware they are of the inequalities that surround them. I was so impassioned by their openness that when I was offered the opportunity to return to Oxford and work at the Winter Institute for a semester, I jumped.

Although my family was concerned about my move there, I was excited to embark on a new journey. I knew it would be rich and rewarding. However, shortly after moving down, I learned firsthand how it felt to be targeted by racists. Leaving a theater after watching Selma, another woman, two men and I were threatened. A pickup drove in front of us in the parking lot. The window rolled down and I could see several young white men. The man in the passenger seat pointed at us and said, “Y’all are gonna die!” and “We’re the KKK.” Then they circled the lot. I couldn’t register all that was happening or all that was being said. I was terrified as they kept circling our car. Fortunately, the threats were all that came. We drove the long way home to make sure they couldn’t follow us.

As I sit here writing about this, I am happy to say that is the only extreme incident I have faced. Through my three months at the institute, I’ve witnessed transformation within communities dealing with segregation in schools and housing, I’ve worked with local students to learn the history their towns hold, and I’ve helped create new media to share the incredible reconciliation and social justice work that has been happening from the campus of Ole Miss.

I also went on my third Civil Rights pilgrimage. With each trip across the South, I have grown more and more into the role that I am supposed to play in creating change.

I am now a pilgrimage singer, combining my passions for soul music and bringing people together around issues that really matter. We fill our voices into the spaces where courageous acts took place. Nothing has been more invigorating than singing freedom songs with our group the “52 Strong” as we joined arms and marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on the 50th Anniversary of Bloody Sunday.

I know now that my unique journey has led me to this point and I can’t imagine a future where I am not addressing prejudice and inequality. Furthermore, I am thankful that these experiences have helped me find my own unique identity and made me confident in who I am. I don’t know exactly where I will end up in life, but I know that I want to be fighting for justice.

Aida Solomon graduated in June 2015 with a degree in Communication. She plans to work as a pilgrimage singer for the next year.