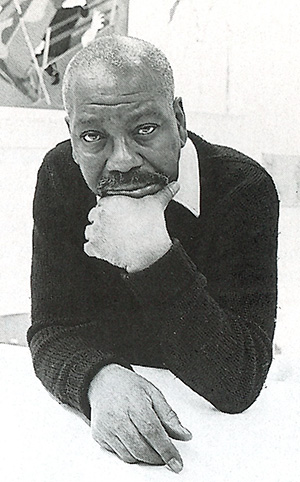

Jacob Lawrence, 1917-2000, was ‘foremost black artist’ of U.S.

Jacob Lawrence, who rose from a rough childhood to become one of America’s most passionate chroniclers of the African-American experience, died June 9 at his Seattle home after a battle with lung cancer. He was 82.

Jacob Lawrence, who rose from a rough childhood to become one of America’s most passionate chroniclers of the African-American experience, died June 9 at his Seattle home after a battle with lung cancer. He was 82.

Born on Sept. 17, 1917 in Atlantic City, N.J., Lawrence was the first African-American artist to exhibit in a mainstream New York gallery. In 1941, at the age of 24, he created a sensation with an exhibit of his “Migration of the American Negro” series, depicting the flight of African Americans from the South. It became the first work by a black artist to be part of the collection at the Museum of Modern Art.

Lawrence came to Seattle in 1970 with his wife, artist Gwendolyn Knight, and joined the UW faculty in 1970 as a visiting artist. He was appointed a full professor of art the following year and was a renowned painting teacher until his retirement in 1983. “Everyone loved him so much,” says Art Professor Emeritus Michael Spafford. “I can’t think of anyone who doesn’t feel that way.”

Lawrence overcame much turmoil in his life to achieve success in the arts. He was abandoned by his father, a railroad cook, when he was seven. Lawrence and two younger siblings lived in foster homes until joining their mother in Philadelphia, after which they moved to Harlem. His mother later enrolled him at the Utopia Children’s Center, where he began to study art. He later studied at the American Artists School and the Harlem Art Workshop.

By the age of 30, Time magazine rated him “the foremost black artist in the United States.” His work, usually in a narrative series of small paintings, explored racism in America, intermarriage, discrimination in public schools, and the progress of the civil rights movement.

He was commissioned to create many prints and murals, including a 72-foot-long mosaic that is to be installed in the Times Square subway complex at Broadway and 42nd Street in 2001. One of his murals, “Theatre,” graces the walls of Meany Theater on campus. He was painting until just a few weeks before he died.

“I think of him as one of the great figurative formalists of the century,” Spafford adds. “He really altered the art landscape of the Northwest, and his career blossomed here, although you wouldn’t expect that, coming from a hub like New York.”

Beyond his talent, Lawrence is remembered for the way he worked with students. “To me, he is the ultimate mentor of people,” recalls Curator Beth Sellars, who organized the 1998 exhibition of Lawrence’s work at the Henry Art Gallery. “His kindness, thoughtfulness and generosity—both he and Gwen, actually, because I think of them as one. So much of what he accomplished was through her sheer strength.”

Today, his work is in the collections of 200 museums, including the National Gallery of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Harlem. In October, the University of Washington Press will publish the Jacob Lawrence catalogue raisonné, a definitive documentation of more than 900 of Lawrence’s nearly 1,100 art works.

Donations to the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation may be sent to the foundation at 300 Commercial St., No. 2, Boston, MA 02109.