Key players at UW recall the tense days of May 1970

The Kent State Killings left many college campuses in revolt. UW administrators look back at how they defused a time bomb.

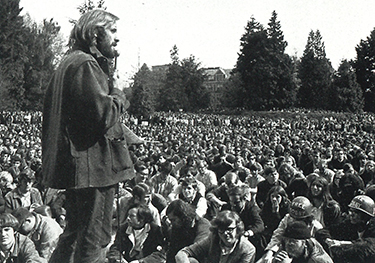

Peaceful crowds of up to 10,000 students marched against the Cambodian invasion and the Kent State deaths. Photo by Grant M. Haller.

On a mild spring day, 7,000 angry UW students, upset over the death of four students at Kent State and President Richard Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia, were marching on the Administration Building to confront President Charles Odegaard. It was May 5, 1970, and while many other college presidents hid behind their office doors, Odegaard decided that it was his responsibility to meet them.

The tide of humanity gathering south of the Administration Building represented almost one-fourth of the entire student population. Those waiting were indignant, possibly hostile and certainly unpredictable. Odegaard turned to a campus police officer and only half-jokingly asked, “Do you think they’ll hurt me today?” The officer answered, “You’ll be as safe as you were in your mother’s arms—we’ll be with you.” “But you don’t know if my mother ever dropped me,” Odegaard responded.

The President walked through the door and into the sea of protesters, who immediately began to jeer him. Holding a red, white and blue bullhorn, he took a deep breath and said, “This is a sad day for all of us across America.” He then read a telegram he had sent to President Nixon, urging the President to “develop a foreign policy which has more support from the American people” because the Cambodian invasion had “caused great frustration and anger among many of our people, not just revolutionary dissidents.”

The ridicule stopped and the throng cheered. Then Odegaard gave his answers to the protesters’ demands. He rejected the idea that ROTC, military recruiting and classified research be dropped. He refused to disavow summoning the National Guard, if necessary. He said, “I’ve heard your voices, but I’ve also heard the voices of those who claim they are entitled to protection.” The crowd yelled “Strike, strike!” and moved out to march through the University District.

Odegaard had good reason to be wary. On this first day after the Kent State deaths, students at more than 100 colleges and universities boycotted classes. There had been violent confrontations. Police had used tear gas against protesters at Yale, Wisconsin and Berkeley, and students had used it against police at Southern Illinois University.

During the next two weeks, university authorities tried to control the rising protests. Governors sent National Guard units to state universities in Wisconsin, Ohio, Illinois, New Mexico, Maryland and Kentucky. Governor Ronald Reagan closed all 28 units of the University of California for four days. More than 200 colleges closed for one day and 19—including Princeton—remained closed for the term.

ASUW President Richard Silverman addresses the crowd gathered at the HUB Yard for a noon rally.

Seattle Times photo.

In spite of these precautions, during May violence swept college campuses across the nation. The ROTC building at the University of Kentucky was burned to the ground, and the firebombing of a dormitory at the University of Ohio caused $125,000 damage. Maryland—once known for football and beer—suddenly saw 350 state and local police and 80 National Guardsmen clash with students, leaving 75 injured and 157 arrested. At Wisconsin, six fire-bombings and repeated window-breaking sprees caused more than $300,000 in damage. Stanford University saw $580,000 in damage and one sociology professor lost 20 years of data in a fire caused by rioters.

During these same days, it became clear to Odegaard and his staff that protest at the UW was nothing like the turmoil at comparable universities. A UW report, for example, put the total cost of the May disturbances at $41,238, including overtime pay for the police. Protests at the University of Washington were dominantly peaceful and aimed at changing foreign policy through legislative processes. Though the media often focused on student radicals, the majority of dissenting students here and across the nation were moderates.

UW students used basically non-violent tactics. Richard Silverman, the ASUW president, refused to host the noon HUB Yard rallies unless radicals agreed to a vote on tactics by all the participants. For example, the May 5th rally ended with a non-violent march to I-5. When confronted by the state patrol, the students voted to leave the freeway. The protesters were a model of self-control. After they marched on the federal courthouse in downtown Seattle, they even picked up their own litter.

There were some threatening events at the UW. Extremists barricaded campus entrances and occupied buildings. Fifteen students were injured in May 7 skirmishes with the Seattle police and antagonists tried to injure UW authorities at least three times. But no one had to call the National Guard, tear gas was not fired on campus and Mace was used only once.

Why was there relative tranquility at the UW? The 1968-69 ASUW president, Thom Gunn, credits “a unique Northwest approach to things.” He cites “an intelligent, problem-solving approach. Therefore we were more successful with less angry outbursts.” Young Socialist Alliance leader Stephanie Coontz remembers being “part of the anti-war movement that didn’t get the most publicity, those who insisted on massive, legal, peaceful demonstrations.”

While student attitudes certainly were a factor, perhaps the key to containing student unrest was the response by the UW administration, which created an “atmosphere less friendly to continued frenzy,” says 1970 Faculty Senate Vice-Chair Vernon Carstensen.

Other major actors of that time—Odegaard, former Vice President for Student Affairs Alvin Ulbrickson, former Dean of Arts and Sciences Phillip Cartwright, and the current UW police chief, Michael Shanahan (who was assistant chief in May 1970)—all agree: UW authorities prevented serious problems. Their success was based on shared principles, strong leadership and effective decision-making, which included good communication with local police and government officials.

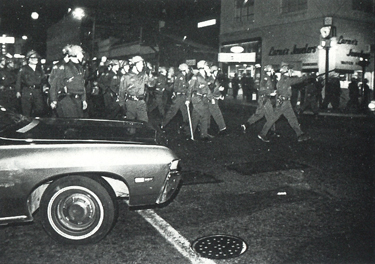

Several tactical squads of Seattle police patrol the University District during a night of disturbances on May 7, which included window-breaking and vigilante incidents. Seattle Times photo.

During those days in May, the Administration Building’s fourth floor command center sometimes resembled Churchill’s war room during the London blitz. On a day when demonstrations were expected, vice presidents for student affairs and for business and finance would meet with UW and Seattle police representatives, a UW lawyer and members of the Faculty Senate. Sometimes students—even ASUW leaders—would attend.

Information at the meetings would come from Ulbrickson and his Student Affairs staff, who knew many student activists. Sometimes the staff would hang out at local taverns, eat pizza and listen to conversations. It was a “Land of Oz” situation, Ulbrickson remembers. Even though the staffers represented “the other side,” protesters sometimes sat with them to describe their plans.

In the “war room,” the informal committee would discuss possible plans of action. According to Cartwright, Odegaard always made the primary decisions, but Ulbrickson remembers that the President also “carefully considered everyone’s perspective.” Protest guidelines were simple and few, the officials recall. Dissenters, having not only rights but also the sympathy of UW leaders, were tolerated and encouraged to remain peaceful. They were also encouraged to take their grievances to the community and the government.

Ulbrickson says the goal was always to gain the “heart and minds” of the non-violent majority. In the UW plans, radicals would be prevented from obstructing movement or stopping others from using facilities. When it was necessary to confront extremists, both a University official and a UW police officer had to read the criminal trespass warning. They would try to make the consequences clear to the protesters. If illegal action did not cease, police would be used.

UW police had their own set of tactics: never corner a crowd; always give them a physical escape route and a psychological outlet. Shanahan credits the wisdom of former Police Chief E.O. Kanz for the policies. The UW police felt that success meant few or no arrests, no violence on either side and the fostering of self-discipline among the crowds.

These principles and tactics were not new. They had evolved over the course of the 1960s, particularly since the Black Student Union sit-in in 1968. Now they would face their strongest test as crowds of thousands instead of hundreds marched.

The crisis was felt from the moment the news of the Kent State deaths swept the campus on May 4. Students scheduled a mass meeting for May 5 and Ulbrickson heard a rumor that there was a possibility of violence. Faculty Senate leaders responded by suggesting teach-ins for May 5 and by agreeing that students should be excused from classes to go to the rally. Like the students, the faculty and administration felt sorrow and anger over the Kent State deaths. The whole idea of the university had been violated. Odegaard remembers an “overwhelming emotional response” and his belief that the deaths couldn’t be accepted “quietly.” Carstensen remembers it as a “bad, bad situation …. This isn’t the kind of nation that Jefferson and his friends were starting.”

The Kent State killings also provoked an unprecedented action by UW officials. It had been a policy to never publicly express a political opinion. Now, on May 5, the President of the University was going to read his telegram to Nixon. Odegaard now says the deaths were “one step toward extremism” and so “excessive” that he just “went ahead” and read the telegram.

On May 6 Odegaard took another unprecedented step. Classes at the UW would be cancelled on May 8 as a memorial to the Kent State deaths. In its 108-year history, the University of Washington had never been closed to commemorate any event associated with political controversy. “There was so much pent-up emotion that there had to be some release. We had to find a way to say, ‘Yes, this is an unusual event,'” Odegaard recalls.

At the May 6 noon rally, Odegaard announced the closure, stating those who had “not been involved in active dissent before” were “deeply moved and disturbed.” Once again, he asked the students to keep their conduct peaceful. The students took a vote and rejected militant action on campus in favor of marching downtown via the Central District. On their return, radicals persuaded about 1,800 marchers to block the freeway. They were chased, clubbed and gassed by police, state troopers and sheriff’s deputies, the first serious police action of the week. UW officials were dismayed but resigned. Both Cartwright and Odegaard considered some clashes inevitable.

Thursday, May 7, was the turning point in the protests. It had become clear that violence was advocated by less than 200 of the thousands of protesters, according to a later University report. But the disruptions of May 7 included clashes between UW protesters and the Seattle Police Department never experienced before or since.

During the daytime, most of the protest activities were conventional and composed. Students at the noon rally voted to begin a leafleting and doorbelling campaign and by evening they had delivered 100,000 leaflets. But the militants had other ideas. By 9 a.m. they had closed the 40th Street and 17th Avenue campus entrances. Others marched through classroom buildings. While police were able to disperse the morning crowds peacefully, by the afternoon protesters entrenched themselves at the two entrances and built small fires.

Ulbrickson and Shanahan had the unenviable duty of reading the trespassing warning at the 40th Street entrance. The UW police officer remembers the crowd throwing rocks, bottles and even lumber from the Central Plaza construction project. “I read fast and ran fast,” he recalls.

While Shanahan and Ulbrickson were clearing barricades, Odegaard was meeting with Acting Mayor Charles Carroll and other city officials. Predictably, Odegaard delivered a lecture on dissent. If the Vietnam War stopped, so would the demonstrations, he told them. Moderates were keeping protests peaceful and these demonstrations were not a problem of the University but of society.

While the heads of the city and the University were in agreement, at times there were incidents of violence between the Seattle police and the UW community. Shanahan remembers one particular May 7 incident, when protesters broke windows at the Applied Physics Laboratory and Schmitz Hall. A busload of Seattle police arrived and used chemical Mace and nightsticks, driving the crowd into Lander Hall, a student dormitory.

When UW police arrived Shanahan was wearing blue jeans instead of a uniform. The protesters let him in the building, but when he identified himself as a police officer, some muttered, “Let’s get him!” Shanahan, a Vietnam veteran, remembers thinking,

“Well, you made it all the way through Vietnam and now you’re going to get it.” But suddenly a black man spoke out, “Don’t hurt him, he’s my boss.” Officer JD. Moore, a plainclothesman assigned to Lander, stepped forward. The surprised crowd was calmed when the two officers then took care of an injured protester. The protesters said they only wanted to safely escape the dangers they feared in the University District. So the UW police escorted them to their cars and then drove behind them until they crossed the University Bridge.

Meanwhile, groups of middle-aged men in civilian clothes began beating students and others on and near campus. When University police discovered a confrontation on “Hippie Hill” behind Parrington Hall, these “vigilantes” identified themselves as Seattle police. A later Seattle Police Department investigation disclosed that some vigilantes were plainclothes officers. Customary police practice is always to send a plainclothes unit along with a uniformed tactical squad. But there were at least three other menacing groups in the district that night. According to Carstensen, who read an official report on the incident, two of the groups met in the dark and grappled with each other, not realizing they were both vigilante units.

But University officials didn’t then, and don’t now, criticize the Seattle police. Odegaard speaks of the long-lasting “good working relationship” they shared. Shanahan believes that “they did a good job” and “kept the lid on.”

On May 8 the University was closed, but Odegaard and others kept on working. Before noon, Odegaard was thinking about his speeches at the student rallies. He believed the students “hadn’t paid much attention (at earlier rallies). I got to thinking, they are my students and I’m going out there.” As he walked through the crowd of 10,000, someone large and strong grabbed him from behind. “I gave him a big shove,” he recalls, and other students pulled the attacker off the President. “I never looked back,” he remembers.

But the week of protest took a personal toll on the then assistant chief Shanahan. He recalls being “really depressed by it all.” The violence and emotion were like “a mixmaster.” Carstensen says, “To the extent I had any nerves left to feel anything,” by Friday “we’d either turned a corner or gotten over the hill.”

By Monday, May 11, class attendance was returning to normal. Student groups had split. The Young Socialist Alliance advocated peaceful protest and established, with University approval, a “strike coalition center” in a vacant building that once housed the Air Force ROTC program. But the more radical Seattle Liberation Front leaders, among them Visiting Philosophy Professor Michael Lerner, occupied the Commons dining area of Raitt Hall. Shanahan remembers the incident as potentially explosive, but the throng departed after taunting the police.

Just as events were cooling down, an incident in Mississippi threatened to blow the campus apart. Two black students were killed at Jackson State University in Jackson on May 14. Odegaard remembers his sorrow and felt “consternation” that these deaths could cause more weeks of violent protests.

On May 15 about a thousand students marched on the Administration Building and demanded another closure in memory of the Jackson State deaths. Odegaard, after consulting with faculty, the attorney general’s office and UW police, closed the UW on May 18.

The day after that closure, Odegaard issued an “open letter” in response to renewed demands that ROTC, classified research and military recruiting be banned from campus. He wrote that he was disappointed in the students for turning from the peace movement to internal University issues. He hadn’t the authority to grant their requests even if he had approved of them, he added. He stated that the University was not, and should not become, “a democracy.” “The University is founded on the proposition that some people know more than others,” he wrote. “To convert it to an egalitarian democracy, with all votes equal, would be to repudiate the qualitative pursuit of learning.”

With that letter, the days of May came to an end.

There were guiding principles which affected everything University leaders did in May. First, they agreed that the University must protect the rights of dissenters, but at the same time must never allow protesters to infringe on others’ rights. Second, they felt they had to preserve what was unique about a university: its tradition of consultation and shared governance.

Those who watched Odegaard in 1970 believe his leadership was the key to calming the campus. Ulbrickson emphasizes that Odegaard should “receive the credit.” Shanahan says, “We were making decisions based on how we felt, what was the human and the right thing to do.”

Former ASUW leader Gunn agrees. “We were treated pretty well by the administration. We had small arguments and differences of opinion—it was the same with city authorities—but by and large everyone took an intelligent approach. After all, the University, Seattle and the state of Washington were not sending people to Vietnam.”

Commencement ceremonies on American campuses that year were subdued, if they were held at all. Cal Berkeley and Boston University, for example, cancelled them entirely, while at Tufts University almost the entire senior class boycotted the events. But at the UW, parents and students gathered at Hec Ed, where peace symbols adorned the tops of some mortarboards and Odegaard took the unusual step of defending UW protesters to their parents.

“By the thousands they strived on course and did not join the ranks of revolutionaries,” he declared. Instead they decided that “we are American citizens, we are concerned with the values and the fate of our country. Let us go and talk to others and try to work within the system to improve America.” Odegaard said their activities had been “too little appreciated.” His words to the graduates were emotional. He said that because he had spent so much time with them, he called them ” my students. And I say my students with genuine feeling.”

Where are they now?

Stephanie Coontz, a Young Socialist Alliance leader, received a master’s degree in history from the UW in 1970. She is now an historian, writer and teacher at Evergreen State College. Her book The Social Origins of Private Life: A History of American Families won a 1988 Governor’s Writer Award. “We played an exceptionally important role in ending the war in Vietnam and I’m very proud of it,” Coontz observes.

Thom Gunn, ASUW president in 1968-69, now runs the Whidbey Island Fish Market and Cafe, in Greenbank, Wash. Gunn describes the student protest era as a “golden age” in Seattle’s history, “not so much for what we did but the ambience of the city and state at that time. It was a great time to be young and alive.” Looking back, he believes the movement might have been more successful if it had been less confrontational.

Michael Lerner, visiting professor of philosophy in 1969-70, was indicted for his political activities as a member of the “Seattle Eight.” The charges were later dropped. He received a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of California at Berkeley in 1972 and then became assistant professor at Trinity College, Hartford, Conn. Lerner was co-editor of the 1972 book Counter-Culture and Revolution, author of the 1973 book The New Socialist Revolution, and East Coast editor of Ramparts magazine. He is now editor of Tikkun, a magazine published in Oakland, Calif.

Richard Silverman, ASUW president in 1969-70, received his master of political science degree in 1970. Described affectionately by his father as a “ski bum,” Silverman is also one of the MCs for the Telluride Film Festival held in Telluride, Colo., where he lives. He is currently on a four-month visit to Eastern Europe during which he will judge a film festival in Poland and plans to ski in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Switzerland.