Last residents moving out of historic Conibear Shellhouse

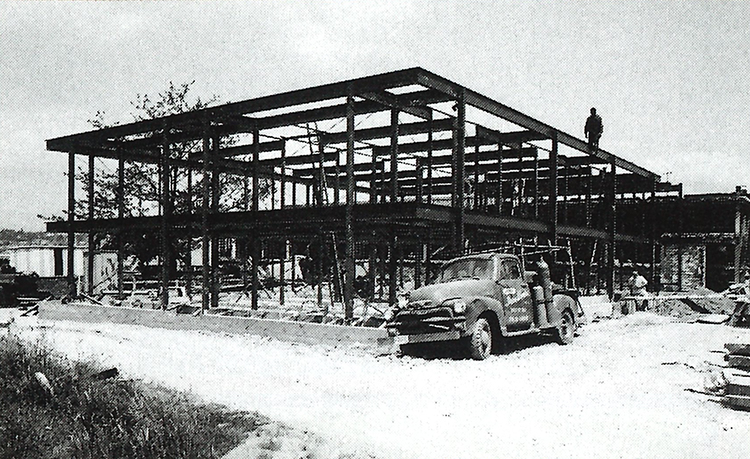

The dormitory wing of the Conibear Shellhouse under construction in 1963. Photo by James Sneddon.

For 45 years the Conibear Shellhouse on Lake Washington was the home not only of racing shells, but also of many of the men who rowed in them. But with the opening of the school year in a few weeks, the last student-athletes will be moving out of the facility forever.

The NCAA has banned athlete-only dormitories starting in 1996 and UW athletics officials felt now was the best time to close the living quarters in the facility. The house’s dormitory wing held up to 72 male student-athletes from all sports, though crew members were the most likely residents.

When the crewhouse first opened in 1949, living conditions were primitive, to say the least. Athletes slept out-of-doors in bunk beds, sheltered only by a fiberglass roof and some canvas tarps.

“All we had was one closet and one phone for all of the men,” recalls former Crew Coach Dick Erickson, who lived in the house from 1954 to 1958. “In another room there were war surplus dressers and lockers. But it was great. It was perfect. Those were the best days of our lives,” he recalls.

Pranks were common. “You never just jumped into bed because you never knew what you were going to crawl into,” Erickson recalls. The proximity of a garbage dump (now the Montlake parking lot) meant nightly visits from rats. “We used to shoot rats with .22s right from our bunks,” he says.

Crewhouse residents sun themselves from the balcony as others play volleyball in 1990.

In 1956 then-football coach Darrell Royal started sending his players to the house to live during Fall Quarter, and the tradition of sharing the house with athletes from other programs began. Over the years members of football, basketball, baseball and every other male team would live there.

In 1964 the UW added a new living quarters wing with 38 rooms. For the next 20 years the house took on many of the characteristics of a fraternity—without the late-night parties since rowers had to get up at dawn for practice.

This 1954 cover of Columns, when the publication was a campus humor magazine, is one twist on life in the 1950s crewhouse. Illustration by Ed Hanson.

Traditions from the era could still be found last year, reports Bob McLaughlin, one of the “house parents” who lived in an apartment in the complex from 1993 to its closing. If a student was caught eating or drinking in the Captain’s Room, where the TV and VCR reside, they would have to “lake” themselves. That meant voluntarily walking down to the dock, taking off all your clothes and jumping into Lake Washington, no matter what the temperature.

But as time went by, Erickson reports, the house “did not keep its intimate character. The population has slowly changed on a yearly basis. There was a short period of time when we had non-athletes living there.”

Saddened to see it close, Erickson says, “The place has outlived its original usefulness.” While plans are not yet final, that area of the shellhouse will probably be remodeled for meeting rooms, offices and as a special weight room for crew members.