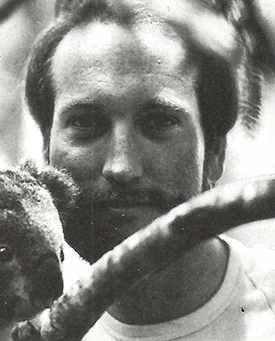

Michael Hutchins, ’75, ’84, is among global animals’ best friends

UW alumnus Michael Hutchins may not have the whole world in his hands, but he has some influence over the fate of more than 70 species currently threatened with extinction. These include Africa’s lowland gorilla, the California condor, the rhinoceros and China’s giant panda.

UW alumnus Michael Hutchins may not have the whole world in his hands, but he has some influence over the fate of more than 70 species currently threatened with extinction. These include Africa’s lowland gorilla, the California condor, the rhinoceros and China’s giant panda.

Hutchins administers the captive breeding program for the American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums, representing 162 North American zoological institutions. Based in Bethesda, Md., it oversees efforts to breed endangered species in captivity and then, when and if conditions permit, return them to the wild. Experts from his group also move individual animals from habitat to habitat to protect genetic diversity when a particular population becomes isolated and, as a result, dangerously inbred.

Born in rural Iowa in 1951, Hutchins became interested in zoos as a UW student. He was especially intrigued by a Woodland Park Zoo program to save the snow leopard. He received a bachelor’s degree in 1975 with a double major in animal behavior psychology and physical anthropology and a Ph.D. in animal behavior in 1984. Although it’s probably a safe bet that he’s rarely met an animal he doesn’t like, Hutchins has a personal soft spot for mountain critters such as snow leopards and mountain goats. He’s also partial to island-dwelling animals, especially the tree kangaroos of Australia. Closer to home, he and his wife share their domicile with two dogs and “a couple of (Egyptian) fruit bats” one of which was born in their home.

Lavish in his praise for his UW education, Hutchins’ travels have carried him worldwide, including the tip of South America where he assisted UW Environmental Studies/Zoology Professor Dee Boersma in a project to band 3,000 penguins.

Hutchins says returning zoo-bred endangered animals to the wild is often complicated by a requirement to control whatever threatened the species in the first place. The endangered Virgin Islands boa constrictor, for example, can’t be reintroduced to its native habitat until something is done about the rats that feed on the snakes’ eggs and young.

Captive breeding involves some tough choices, starting with selecting which threatened species will be invited aboard what Hutchins called “the zoo ark.” There just isn’t enough space to save them all. One selection criteria is whether the creature qualifies as what Hutchins calls a “flagship animal,” that is, a species “the world would be a whole lot worse off if we lose.”

Captive breeding requires careful matching of animals to avoid inbreeding and to preserve a large, healthy genetic pool. It’s been referred to as a “computer dating service for animals,” Hutchins says.

Captive breeding also presents tough ethical questions such as how much human attention to give animals that will later have to survive in the wild. Even more difficult, zookeepers must decide when is it appropriate to destroy an individual animal that may be “surplus” or a possible hazard to the genetic pool. The issue can bring zoologists into conflict with animal rights activists. But for him it’s a question of what’s more important, the species or the individual and, much as he loves animals, Hutchins comes down on the side of what’s best for the species.