Once a death sentence, cancer is a new way of living for one survivor

Jean Reichenbach. Photo by Mary Levin.

My grandmother died of ovarian cancer in 1956. I was 19 years old and I remember thinking, at the time, that science would find a cure long before I was old enough for cancer to become a threat. I was wrong.

Just how wrong became apparent in January 1992, when a physician discovered a “mass” in my abdomen adjacent to my lower bowel. My first hint that something was amiss had come only two days earlier with an ominous and rapid accumulation of fluid in my abdomen, a condition called “ascities.” On Saturday I could button my blue jeans. When I woke up on Sunday the waistband didn’t even come close.

I knew from the outset that I had some form of cancer because the doctor didn’t equivocate. “If it’s ovarian, we can cure you,” were his words, as I recall them. “If it’s anything else, we can’t.” I took the news calmly, agreeing that immediate hospitalization was the most prudent course of action. The tears, the terror, didn’t hit until hours later, sometime deep in that first, sleepless hospital night. And it was months before the real subtlety of his statement hit me. “We can cure you” doesn’t necessarily mean “We will cure you.”

In fact, on that first day his unspoken estimate for my long-term survival was less than 10 percent. Almost two years later, those odds have improved five-fold or better. The intervening months have been tough—both physically and emotionally—but luck and recent advances in aggressive cancer treatment have been on my side. At my side throughout have been two UW-educated physicians: gynecological surgeon Michael R. Smith, ’62, and oncologist Robert F. Lane ,’69, ’73. I consider these skilled, patient, compassionate men to be the best in the business.

I was one of about 21,000 women in the United States diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 1992. It’s the fourth most frequent cause of cancer death in women in the U.S., killing 12,000 each year. One in 70 newborn girls can expect to develop it sometime in her lifetime. It’s most often discovered between 55 and 59 years of age (I was 54). Although not clearly hereditary, the risk is higher when a mother, sister or daughter has had the disease.

Lacking good techniques for early detection, ovarian cancer is often well advanced before discovery, even in women who, like me, have regular gynecological checkups. But there are signs to watch for, including appetite changes and unexplained chronic indigestion. I now know that the stubborn indigestion I began to suffer about six months before diagnosis was a warning signal. I had dismissed it as a reaction to stress.

My disease was discovered late, but my treatment began with stunning swiftness. Less than 48 hours after the discovery of the tumor, I underwent surgery for a total hysterectomy, removal of part of my large bowel, and the painstaking surgical process of removing the cancer that had spread to almost every corner my abdomen, plastered itself to the lining of my abdominal wall, and attached itself to, although not invaded, several major organs including my large intestine and liver.

Removing it all was out of the question. Fortunately, the bits of tumor my surgeon had to leave behind were no bigger than one-quarter inch—within the killing range of subsequent chemotherapy, if the drugs worked. I left the operating room with at least a fighting chance.

I have two clear memories of the intensive care unit where I spent my first post-operative days. One is of someone, perhaps a nurse or technician, asking why I chose to have “such a big surgery in such a small hospital?” In truth, the staff and facilities at Seattle’s Northwest Hospital were more than equal to the job. My second memory is that, despite the tubes, the wires, monitors and other medical paraphernalia, someone washed my hair.

On the other hand, I have no memory of my husband delivering the “good news,” if it can be described that way. My cancer was ovarian—the one possibility that offered a shred of hope.

It was a pretty flimsy shred. “Without further treatment I give you a year,” my surgeon predicted a few days later. “With treatment, I give you a year after that.” That sounds harsh but, as he explained later, he’s concerned that doctors “tend to sugar coat these things.” In my morphine-clouded state two years actually sounded like a long time.

Eleanor Cole Hickey, Jean Reichenbach’s grandmother who died of ovarian cancer in 1956.

Shortly after my hospital discharge I began four courses of standard outpatient chemotherapy. The long-range plan, as outlined by my oncologist, called for these four treatments to be followed by two courses of very rigorous, high-dose chemotherapy that, at that time, had rarely been used against ovarian cancer.

Called CEP after the three chemicals used (cyclophosmide, etopomide and platinum), the high-dose treatments would reduce my white blood cell count to near-zero, leaving me potentially vulnerable to life-threatening infection. Each would require up to a month in the hospital and they would not be pleasant. “You may feel like you’re going to die,” he explained. “But you won’t.”

Curiously, I wasn’t especially afraid of the prospect. My big fear was that some weakness in my system—perhaps heart or kidneys—would disqualify me from the draconian-sounding regime.

Meanwhile, spring passed in a haze of chemo-induced nausea, long naps and frustrating periods when I was too ill to drive to my almost-daily doctor appointments. I worked when I could and enjoyed outings when I felt strong enough. One afternoon, returning from an especially pleasant lunch with friends, I found an $11,000 bill for oncology treatments in the mail. Even with good insurance, that kind of news doesn’t exactly make your day.

Several other events stand out from that period. First, I started losing my hair on Feb. 27, our 32nd wedding anniversary. I discovered strands of it on the pillow when I awoke that morning. Over subsequent days hair clogged the shower, clung in clumps to my brush and littered the house like the residue of a shedding dog. My scalp was sore. I’m told some people preempt the process by having their hair shaved off. A good idea, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it.

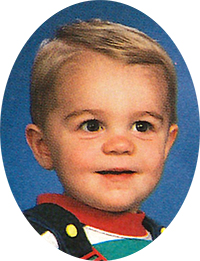

The second event was a miracle of timing. On March 2, the day before my second outpatient chemo treatment, our first grandchild, Kyle Jacob Reichenbach, was born. A day later and I would have been too nauseated and exhausted from an eight-hour chemical infusion to visit the hospital and welcome him to the world.

Mid-April brought the first hopeful news. A blood test indicated that my tumor appeared to be yielding to the chemotherapy. That bolstered me when, a week or so later, I was back in the hospital to have about a liter of marrow withdrawn from my pelvic bones. Bone marrow transplantation, long used against leukemia and lymphoma, is now being tried against breast and ovarian cancer. “Banking” my own marrow in the high-tech freezers at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center preserved this option should more traditional chemotherapy fail.

Meanwhile, I would undergo the high-dose CEP treatment which my oncologist described as coming “as close to a bone marrow transplant as we can get and still get the insurance to pay.”

Or so we hoped. In fact, my husband and I had to decide whether we could, or would, pay for the treatment ourselves if our insurer disqualified me on the grounds that CEP for ovarian cancer was still “investigational.”

Without hesitation we decided to go for it. We could mortgage or sell the house if necessary.

Fortunately, my insurance covered the $90,000 price tag that accompanied what ultimately added up to nearly 50 days in the hospital. But I still think about women who have no insurance or no house to mortgage.

A back-to-school essay on “How I Spent My CEP Summer of ’92” would read something like this. June began with a week in the hospital for intravenous infusion of the three chemicals. Next, a few days at home growing progressively sicker as my white blood cell count fell into the danger zone. Then, back into the hospital where intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and blood and platelet transfusions kept my system in balance and infection at bay until my chemo-zapped bone marrow recovered its ability to fight infection. Visitors outside the family were discouraged. Contact with children, including my infant grandson, was out of the question. “Garbage pails of disease,” was the way one physician cheerfully described children. Flowers were forbidden because bacteria grow in the water that sustains them.

My son made every-third-day visits to the blood bank to donate the precious platelets that protected me from internal bleeding—the gift of life returned from someone to whom I had given life.

Except for one frightening night when my temperature rose above 104 degrees and stubbornly clung there, the experience was mostly uncomfortable boredom. Lacking the energy or concentration to read, I drifted in and out of sleep. Even fear and anxiety yielded to my listlessness. Political conventions and Olympic athletes paraded across the television screen. What I, with my queasy stomach, remember most clearly was the frequency with which food is advertised on TV.

Kyle Jacob Reichenbach, shown here at 18 months old, was born between chemo treatments.

Then, after about two weeks, my bone marrow started to perk up and my white blood cell count responded. Up one day, down the next, then up again. Finally, I could go home. Then, after a one month rest, the whole process was done a second time.

By late summer the long road of chemotherapy was over. Reeling with nausea and diarrhea, requiring twice-daily, hours-long infusions of intravenous fluids to keep my blood chemistry in balance, I was home at last, to stay. My daughter—on vacation between her first and second years at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government—arrived to help me. Friends and professional colleagues offered support. Books, flowers, food, poured in. My husband gained weight on my friends’ excellent cooking. My appetite had long ago disappeared. At one point my weight fell to what I’m willing to admit to on my driver’s license.

And then, just when I expected to feel at least mildly celebratory that my chemotherapy was over, I lurched into the most emotionally difficult period of all. It lasted for weeks and featured two basic themes: First, was my enemy banished? Or, now that the chemical weapons had fallen silent, was my possible killer gathering strength for another assault? Secondly, what do we do now?

Only then did I recognize how much I had built my hopes on the potentially shifting sands of that unproven, leading-edge, high-dose chemotherapy. “Sure, survival statistics for ovarian cancer are pretty grim,” I had bravely proclaimed. “But that’s based on old treatments. Not the state-of-the-art stuff I had.” The truth is that all that state-of-the-art stuff translates into four words which I began to hear over and over again from the medical community: “There is no data.” And there will be no data for at least five years.

My first post-treatment decision was whether or not to submit to a what is called a “second look” operation in which my abdomen would be reopened, examined and biopsied to see if any detectable disease remained. Beyond the physical difficulties involved lay an emotional question: Could I, at that moment, face discovering that the grueling months of therapy had failed? Could I handle the news that I had to start treatment again immediately? Perhaps some kind of hiatus from treatment, a period of not knowing, would be merciful.

We ultimately chose a less thorough, but less risky, “laparoscopic” second look in which a fiber-optics instrument was inserted through a small incision into my abdomen and tissue samples collected for pathological examination. The news was good. The samples showed no residual disease. A similar procedure done six months later yielded the same encouraging result.

But my chances of a recurrence were high, so the issue of additional treatment “just in case” was raised.

Medical opinion was divided. Suggestions ranged from undergoing a “precautionary” bone marrow transplant to doing nothing except wait and watch. The choice was ours.

My husband called cancer specialists in Seattle and around the country seeking at least a shred of consensus. No luck. A physician at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center ruled out a precautionary transplant. The up-to-20 percent mortality risk is unacceptably high for someone who, in his words, “may not need it anyhow.”

Ultimately, I chose to take an oral chemotherapy drug and submit to close monitoring via blood tests and twice-a-year laparoscopic examination. The objective is to catch any recurrence while it’s still microscopic.

On the day we finally made the decision my husband and I agreed that “our new life begins today.” It’s a life that, for me, is built around a central challenge: How do I keep today, with all the good things it has to offer, from being tarnished by fear of what tomorrow may bring?

If cancer was not the death sentence it initially appeared it might be, it has become a life sentence of sorts: a requirement to live by a different set of expectations. It’s a life where longevity can no longer be assumed, where anxiety—sometimes tied to surgery dates and waiting for pathology reports and at other times simply free floating—will be an element for a long time to come.

It’s virtually impossible to chronicle the maelstrom of feelings that have accompanied this journey. The first few weeks after diagnosis were, for the most part, blessed by a kind of emotional anesthesia and, for me, uncharacteristic calm. The mood swings, when they began, catapulted me between euphoria and despair. Curiously, I slept exceptionally well throughout the treatment period. The 3 a.m. awakenings began with the end of treatment.

Certain images have haunted me throughout. My father, who died of cancer in 1976, spent the last six weeks of his life in Seattle’s Providence Hospital. I remember the relief I felt when, at the end of each daily visit, I walked out of his hospital room, out of the building and into the fresh air. I remember the accumulation of prescription drugs that characterized his illness and dying. I remember the blend of grief and relief I felt when, at last, his medications could be cleared away, when daily schedules were no longer constructed around the needs of the sick room.

I thought about the milestones I might never celebrate, the grandchildren I might never see, the “entitlements” I might not live to receive. Surely my years of hard work raising a family and assisting aging parents had earned me a reasonable period of good health and energy to reap the rewards? Part way through my treatments I noticed that the quarterly statements from my husband’s retirement plan—once a source of lively discussion—were being quietly filed away without comment. I still marvel at the confidence with which friends make plans: Hawaii next Thanksgiving, Australia after Christmas. Even ordering tickets for next year’s theater or football season is something of an act of faith. For me the future is parceled out in six-month increments—from one laparoscopic checkup to the next.

On the other hand, this new life has brought me more moments of joy than ever before. I have more confidence in my opinions and I’m more likely to express them. I follow my instincts more. I’m less patient with unsatisfying chores and people. I seek relationships that are rich in ideas, laughter, and intellectual and spiritual nourishment.

Yes, I do stop and smell the roses. I’m also more likely to pause at the window and watch a copper-colored moon change to silver as it rises from behind the Cascade Mountains, even when it means missing the opening scene of “Murphy Brown.”

I procrastinate less. We don’t get unlimited chances to learn something new or find answers to important spiritual questions. If I spend my time one way, I can’t assume a surplus left over to someday revisit the road not taken.

Supportive family and friends notwithstanding, cancer is a lonely experience. The relative rareness of my kind of cancer—ovarian—makes it seem even more so compared to, say, breast cancer which strikes 175,000 women each year.

I’ve only recently begun looking into cancer support groups. My first, tentative investigation led me to a brochure which offered a choice of groups: “Living with Cancer” or “Cancer Survivors.” Where do I fit? Has enough time gone by so I can define myself as a “cancer survivor”?

If I can’t find what’s right, maybe I’ll start my own. Picture the ad in the Seattle Weekly: “Fifty-something woman, more-or-less emotionally pulled together, is muddling through the post-treatment phase of cancer and hoping for the best. Loves reading, music, needlework, the mountains and, most of all, life itself. Seeks others in a similar situation.”

However cancer has changed me, it has not turned me into some sort of combination of Pollyanna and Mother Teresa. I still have moods, headaches, bad-hair days and times when the car won’t start. And I complain mightily about all of the above. Except for the bad-hair days. I’m so grateful to have hair at all that I’ll take it on any terms.

I still “sweat the small stuff’ more than I would like. But I do strive to find something worth keeping, worth learning, in every day and circumstance. I can’t afford to say: “I wish today was Friday.” Most Mondays have something to recommend them if I look closely enough.

I am all too cognizant that, since the initial discovery, I’ve dealt with mostly good news. Bad news, if it comes, will devastate me.

But we go on, my husband and I. That newborn grandson is now a lively, talking toddler. I was there in Harvard Yard, with my hair turning frizzy in the heat, when our daughter received her master’s degree in June. She’s now in a doctoral program. One more Harvard commencement to go. Those quarterly retirement statements are, once again, a source of conversation. We plan vacations and order next year’s season tickets. I have started a quilt that will take a couple of years to complete.

I still have days when I awaken frightened and depressed, when just getting out of bed is a struggle. But they’re less frequent and a little less bleak. It’s somewhat like driving to work on a summer morning when the sun hasn’t quite dispatched the nighttime fog. You hit those gray patches but, for the most part, they’re thin enough to see through. So you keep driving until you reach another patch of sunshine.

Last May, when my second post-treatment laparoscopic checkup revealed no sign of disease, a friend called to congratulate me. “You must feel like you’re standing on the top of Mount Everest,” he said.

The image was good but the scale was wrong. I feel I’ve reached the top of Mount Pilchuck. Everest lies ahead with abundant opportunity to fall into a crevasse before I get there. But my doctors tell me that, given the treatment I received and the way my disease responded, I have a 50 percent chance, one physician thinks a bit better, of reaching that summit of long-term survival.

Keep your fingers crossed for me.

Ovarian cancer: fighting back with high-tech

Physicians at the University of Washington Medical Center began administering high-dose CEP therapy to certain categories of ovarian cancer patients three or four years ago, according to Dr. Stephen Petersdorf, assistant professor of medicine and oncology.

Initially, the risky treatment was limited to women who had failed to respond to other forms of therapy. But as CEP has become safer, especially since the development of a bone marrow growth drug, it has been offered as first-line treatment to ovarian cancer patients who are at high risk of recurrence.

Today, Petersdorf says, CEP for ovarian cancer patients is being superseded, to some extent, by the drug taxol. The UW and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center pioneered the use of taxol, which comes from the bark of the Pacific yew tree.

Petersdorf is one of two acting directors of the expanded Autologous Bone Marrow Transplant/High Dose Chemotherapy service which began operating at the UWMC in July.

Support groups: Please don’t call them pity parties

A young man with brain cancer notices that, since his diagnosis, friends decline to share the can of soda pop he’s drinking. They’re afraid they might catch something.

Another patient likens the cancer experience to that of Vietnam veterans in the ’60s: Suddenly the world is divided into “us” and “others.”

These are just two examples of the isolation cancer patients often feel, says Susan Goedde, a social worker at the UW Medical Center Cancer Center. Isolation that a support group can reduce.

But don’t misunderstand her. Support groups are not “pity parties.” They’re gatherings of people who “know what it feels like” in a way that even the most supportive family and friends can’t experience. They’re places where, unlike the rest of society, having cancer is “normal.” They’re opportunities to share “black humor,” or express frustration at watching those silky-haired models in shampoo commercials when you’ve lost every strand to chemotherapy.

Goedde leads three support groups at the UWMC: one for people with brain tumors, another for prostate cancer patients and a third for young adults with cancer.

“Many people have not been sick a day in their lives and someone says they have cancer,” Goedde observes. Suddenly they’ve lost their previous self. They may feel betrayed by their body. Normal routine is often lost to the demands of treatment. Work falls victim to fatigue. Roles within the family change.

“Cancer isn’t something that happens once” and can be dealt with, she adds. “In cancer, thing after thing happens. You can’t plan. You have to adapt, adapt, adapt, change, change, change.”

The healthiest strategy is to acknowledge feelings of loss and make them part of your life, Goedde stresses.

“What isn’t so good is going numb after diagnosis, putting your life on hold for awhile, thinking it will go away,” she explains, and the “positive-thinking philosophy can backfire.” In both cases, patients risk losing the opportunity for growth that working through losses and adapting to cancer can bring. And don’t worry about being a “bad patient” by showing the way you feel. Forget feeling required to “put on a happy face.”

Above all, don’t equate reaching out to a support group with personal weakness. “If your roof is leaking or plumbing falls apart you go someplace where someone has experience with the problem,” she notes. When the problem is living with cancer, some of that experience can be found in the right support group.

For information on cancer support groups, Goedde suggests calling the American Cancer Society (1-800-227- 2345) or Cancer Lifeline (1-800-255-‘ 5505). For information on the groups she leads, which are not restricted to UWMC patients, call (206) 548-4108 and leave a message on her voice mail.