Our man in Turkmenistan

We talk with Ambassador Allan P. Mustard, ’78, America's top diplomat in Turkmenistan, the central Asian country that borders Iran and Afghanistan.

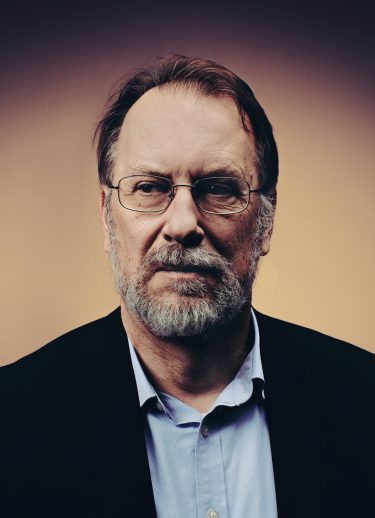

U.S. Ambassador Allan P. Mustard

Before he came to the University of Washington, U.S. Ambassador Allan P. Mustard took classes at Gray’s Harbor College in Aberdeen, where only two foreign languages were offered: Russian and German. Mustard signed up for Russian, and he reached fluency during his time at the UW.

That language equipped him to traverse the globe during the Cold War. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, he became the Resident Sovietologist for the United States Department of Agriculture, at a time when the U.S. was sending Russia the largest food aid package since the Marshall Plan.

During his winter holiday, Mustard came to the HUB for a talk hosted by the Jackson School’s Herbert J. Ellison Center for Russian, East European and Central Asian Studies. Ellison, whose family endowed the center, was a legendary UW professor who taught Mustard in the ‘70s.

Mustard lives in the capital city of Ashgabat with his wife. Since his college days, he has also learned German.

Where did you live during your time at the UW?

I lived in the Russian house, 2104 N.E. 45th St. It was founded in the 1950s by a bunch of Russian students, and it was a place where you could only speak Russian. We had native speaker house parents, a mother and a father, who corrected our Russian and coached us. That’s one of the reasons I learned to speak fluently. The UW was the largest undergraduate Russian program in the U.S. at the time.

Was there a lot of vodka in the Russian House?

I wouldn’t say a lot. We occasionally mixed a punch—the famous Russian House punch. Two gallons of red Kool-Aid, a gallon of red wine, a gallon of vodka, and a bunch of fruit. You leave it overnight, and then just before pouring, you put in a gallon of 7 Up to make it fizzy. All the sugar masked the alcohol. All things in moderation.

What was the highlight of your undergrad career?

I paid my own way through college, so when I finished, I was glad it was over. I worked as a janitor downtown in the summers, in the Suzzallo library as a student bibliographer, and for the golf driving range. I tried to swing golf clubs once. The golf pro told me to put the club down. He said, “You have no talent. Never do that again.”

You were appointed by President Obama in 2014. How did that happen?

I was a senior Foreign Service officer and I was eligible for an ambassadorship. I was in the Department of Agriculture, but colleagues in the Department of State encouraged me to apply. I’m a career Foreign Service officer. Under the U.S. Constitution, the president appoints all commissioned officers. Any time I’m promoted, I’m nominated by the president and then confirmed by the Senate.

For a reader who doesn’t know much about Turkmenistan, how would you describe the country?

It’s 85 percent desert. It is very sparsely populated—about 5 million—and it’s about the size of California. So imagine California filled out by the population of Los Angeles.

What was the first time you went there?

In 1979. It was part of the Soviet Union.

Was there any culture shock?

I can’t say there was a large one. I had spent quite a bit of time in the Turkic world, having served in Istanbul, and in the post-Soviet space, having served multiple tours in Russia.

I was in Istanbul when the Berlin Wall came down (in November of 1989). My wife was back in the States and I was bach’ing it. A good friend of mine who studied Russian at the UW was the U.S. agricultural attaché in East Berlin. She called up and said, “Why don’t you come and spend Christmas with us?” I flew to West Berlin during Christmas, crossed Checkpoint Charlie and came into East Berlin. We watched people passing through the Brandenburg Gate. We went to the West Side with hammers and I chipped some of the wall. Everybody was knocking chips off because they knew it was going to come down.

My wife stayed in the States with the baby because we were having cholera outbreaks in Turkey. So I was still bach’ing it into the summer, when I got a phone call from Washington saying, “The undersecretary wants you to return to be the Resident Sovietologist at USDA.” It was a fascinating job because things were changing so fast in the former Soviet Union, we were scrambling just to keep up. In addition to policy advice to the folks in the hierarchy at the USDA, we did food aid and technical assistance. It was the largest food aid program since the Marshall Plan. At one point we put $800 million in food products into Russia, just as aid. People have forgotten that.

What’s the best and the worst part of traveling for a living?

The best part is seeing new places, meeting new people and making new friends. The hardest part is the move. You pack up everything and they haul it away, and on the other end you have to unpack it all. That’s no fun. I’ve noticed that over the years it’s gotten heavier and heavier. I can’t figure out how that happened.

My mom insisted that I ask you this: Is there a Costco in Turkmenistan, and if not, how do you survive and what do you do on Sunday?

No. We buy food on the local economy. We shop at supermarkets. We buy our fruits and vegetables at wet markets. As for what we do on Sundays: About once a month we have a Sunday matinee. We have a projector in the basement, and we invite people from the embassy community to come over and watch a movie. We’ve shown “La La Land.” In honor of Halloween we showed “Rear Window.”

Some weekends we go out and drive around the city. My wife and I have been engaged in a little cartographic project, mapping the streets of Ashgabat through Open Street map. We’ve done a fairly thorough job of mapping it so far, which makes it easier to find things.

Favorite Turkmenistani dish?

Manti. They’re large meat dumplings.

Any plans for the future?

There may be another posting, or this may be the end of the line. We just don’t know yet. In the Foreign Service, you’re always dealing with uncertainty. When you sign up, you agree to serve wherever they need your services and your skills. Some of our posts have been surprises. I never expected to go to India or Mexico or Turkey, but we seized the opportunities.