Photographer captured Husky Stadium collapse for posterity

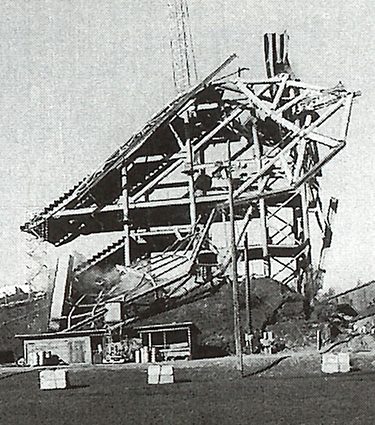

The stadium addition in mid-collapse. Photo by John Stamets.

At 10:07 a.m. on Feb. 25, 1987, the dream of a 17,000-seat addition to Husky Stadium suddenly came crashing to the ground in 12 seconds.

A deafening bang reverberated across the campus that morning as the steel framework for a long-awaited addition crumbled upon itself, an event recorded for posterity by a part-time photographer late for work.

It was truly a miracle that no one was killed, and another miracle that despite the collapse, the North Stands Addition was finished in time for the season opener against Stanford on Sept. 5.

For photographer John Stamets, it started like any other day. He rode his bicycle along a campus back road that skirted Husky Stadium. Because it was a nice day, and because he always carried his camera with him, he stopped to take some construction photos.

“A guy in a hard hat came walking toward me,” Stamets recalls. “‘You ought to take a picture of the crack. Engineers will pay you a lot of money someday for it,’ he told me.”

Stamets did take a picture of a “crack” in the steel framework and saw that the entire structure was empty of steelworkers. Even a maintenance shed was suddenly off limits. “We’re not telling KIRO about this one,” the worker quipped.

Suddenly Stamets’ heart started beating. “You are already late for work,” he told himself. “But what if it does fall down?” He crawled over and under construction trucks to get the best angle and waited. Suddenly he saw a man running hard.

Stamets’ sequence of images of the 1987 stadium collapse.

“I was totally psyched. I just started shooting. Then it started to go. I thought, `Oh my God, it’s happening right now.’ I had been standing there for only 10 minutes,” he remembers.

He hand cranked the film as fast as he could, capturing eight shots as the structure fell upon itself. “It turns out the last shot was the 21st frame on a roll of 20 pictures,” Stamets says.

While shooting the collapse, Stamets admits he was in high spirits, but as soon as it was over, his mood flipped 180 degrees. “I was sure there were dead people. I was really confused. I kept running toward the mess and then running back again.”

There would have been deaths—20 to 40 ironworkers were on the site in the early morning—but once workers discovered a buckle in a roof truss support beam, a construction supervisor ordered everyone off the site.

Investigations later confirmed that nothing was wrong with the design of the North Stands Addition. That day, the structure suffered from inadequate lateral support. Several critical “guy wires”—cables that keep the structure from twisting—were released in error.

The Lydig Construction firm worked seven days a week, sometimes in three shifts, to clean up the mess and start over. “I thought it was impossible to get the stands ready for the first game,” said Bob Brison, the UW’s director of engineering and construction at that time. The Husky Ticket Office even printed the season’s tickets with two different seat numbers—one for Husky Stadium and one for the Kingdome, the alternate venue.

As for Stamets, his photos hit the front pages of most regional newspapers. Local TV stations had a bidding war over broadcast rights. But he later realized that no one had seen the entire sequence in one package.

So that fall he printed several thousand panoramic postcards with the entire sequence, including the headline “Gravity 1, UW 0.” Despite the grumblings of some UW officials at the time, the postcard sold well and continues to be available at the University Book Store.

“I was careful not to sell it in the `U’ District until after three home games were played. And in the caption I clearly state that the collapse was not due to design errors,” says Stamets. “I did not want the card to contribute to some kind of fear of the stadium.”

Ten years later, Stamets now works for the UW architecture department teaching photography to its students. Because it is the 10-year anniversary of the collapse, he plans to issue a framed, limited edition series of the nine photographs.

While fans may chuckle over the images, Husky Stadium remains a premiere sports venue. There is some talk that someday it may get another addition. You might even find John Stamets out there with his camera when it happens.